Some people are made to love and lose themselves in love. Charles de Foucauld had the grace of understanding early on that he had lost his way by attaching himself to disappointing passions and fleeting possessions. Thus he had time to go beyond them and love God instead.

During his solitary expedition to regions where no Christian had yet ventured, he came into contact with Islam and experienced divine transcendence in a religion so far removed from the growing materialism of the West that he considered converting.

However, it was in his family’s Catholicism that God awaited him. More precisely, in a confessional at St. Augustin’s parish in Paris, where Fr. Huvelin invited him to kneel down for a general confession.

The penultimate place

Charles emerged from this confession converted, a believer, suddenly aware of the omnipresence of the God of his forefathers in his life. He recognized God’s providence as constant and attentive, but above all profoundly loving.

A revelation dawned on him: God is Love, and Christianity is the quintessence of this Love. The Church comes to be through the abasement of the Second Person of the Trinity in the Incarnation and the death of Christ on the Cross: “God so loved the world that He gave His only Son so that the world might be saved.” Fr. Huvelin summed up this truth in words that would henceforth light the way for Viscount de Foucauld and make him Brother Charles of Jesus: “Jesus has taken the last place so utterly that no one can ever take it from him.”

Since the King has already taken the last place, his servant would try to take the penultimate place, and imitate him in everything. First and foremost, in his love for God and neighbor, a love that nothing can better symbolize than the Sacred Heart. So it was only logical that, in 1889, Charles should go up to the Basilica of Montmartre in Paris, still under construction, to dedicate himself to the Sacred Heart, that “summary of our religion.”

Consoling the heart of Jesus

From then on, he had only one idea: to reveal to all people this dazzling, infinite, and absolute love, which is extended to all but to which almost no one responds. Consequently, Charles’ other vocation would be to “console the Heart of Jesus.”

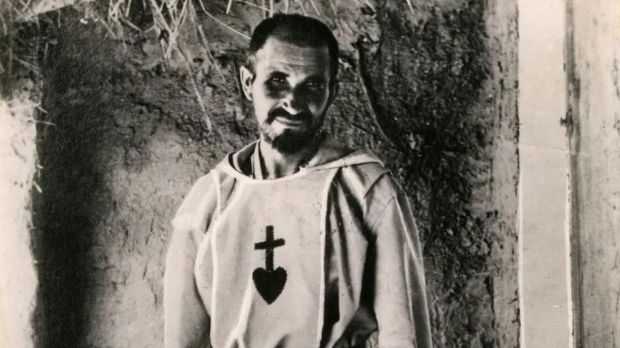

“Loving, imitating, and consoling” would be his rule of life to the end. This vocation required his complete self-giving, not in the Trappist monastery of Notre-Dame des Neiges, as he first thought, nor in Nazareth in the obscurity of a gardener’s job (paths he walked for a time). Rather, it was in the priesthood and the eremitical life deep in the Sahara.

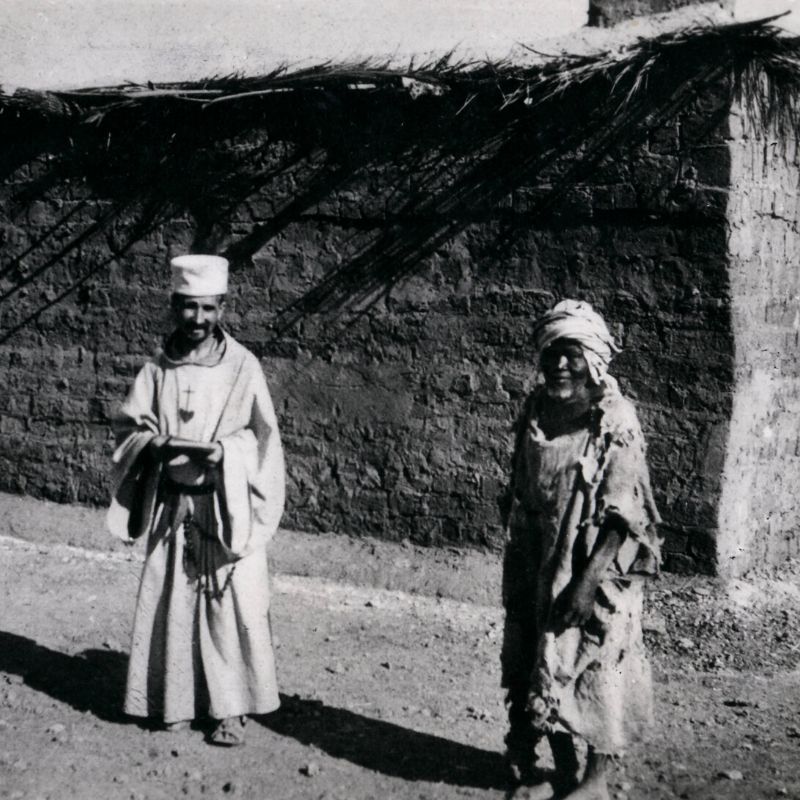

There, no one before him had celebrated Mass and made tangible Christ’s sacrifice on the cross through the Eucharistic presence. He went there to do God’s will, not his own, responding to love with love — even to the point of hoping for martyrdom.

The dark night of the soul

It would’ve been simple if he had experienced tangible graces and spiritual satisfactions, but he didn’t. To the apparent failure of his efforts — he only saw two conversions, and no one went to share his solitude in Tamanrasset — was added the dark night of the soul. His loving one-on-one conversation with Christ in Mass and Eucharistic adoration became a perpetual soliloquy, also apparently sterile.

“Everything is painful for me, even telling Jesus that I love him. If only I could feel that God loves me, but he never tells me,” he wrote to his cousin Marie de Bondy. He knew enough about the mystical life not to be surprised by this, nor to give up for so little reason. “God has never failed man, it is man who has failed God,” he said. And that was enough to keep him going despite loneliness and bitterness, convinced that his mission would one day bear unimaginable fruits of conversion.

Absolute confidence in God

It’s not by chance that he chose to wear the Sacred Heart on his habit, so he would remember “God and mankind so as to love them.” In a burst of confidence in the universal mercy of the Redeemer, he would add, “Make me love you more and more, and make all men and women go to Heaven.” First and foremost, he prayed for the Muslims that many Europeans refused to evangelize.

His clear-sighted prediction was that these followers of Islam, failing to return to their ancient Christianity, would one day turn violently against the country that had failed to love them and make them loved, immensely guilty of having deprived them of grace.

Since he could achieve nothing by his own work, but everything by the work of God, he abandoned everything to the good will of the Lord. He knew that the Real Presence on his poor altar was the only promise of a future for these lands and these souls. And he, who no longer felt any consolation, cried out all the same:

Sacred Heart of Jesus, thank you for revealing yourself to our eyes, for giving yourself to us, for giving us the infinite gift of your presence in the Sacred Host on the holy altar. […] Thank you, Sacred Heart of Jesus, for this excess of kindness, this excess of happiness.

“Jesus Caritas”

His wish to “die a martyr stripped of everything, violently and painfully killed,” was fulfilled on December 1, 1916. The “Universal Brother” who, like his Master, wanted to love all people, was murdered without glory at the entrance to his oratory. Not coincidentally, that day was the first Friday of the month, uniting him for eternity with the loving heart of his God.

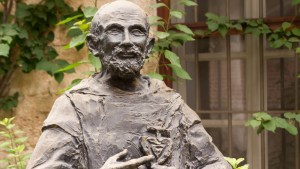

In 1933, the first five Little Brothers of Jesus, the disciples for whom he had waited in vain, took the habit in the Basilica of the Sacred Heart at Montmartre. This is also where, in the crypt’s St. Peter’s chapel, a statue of the Sacred Heart inspired by a drawing by Charles stands as a reminder of the inseparable bond forged with the One who is all love: “Jesus Caritas.”