When your children become seriously ill, how can you find the strength to fight every day? How can you stand up to such hardships and still live with joy? And how can you recognize the beauty around you and surround your children with more and more love?

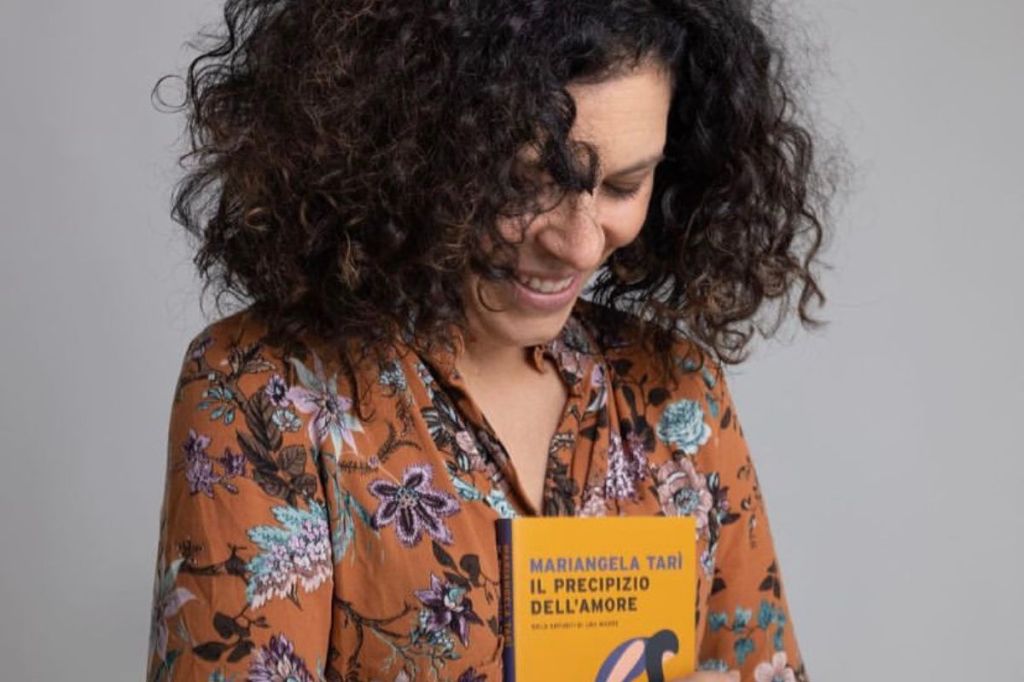

We talked about these things with Mariangela Tari, mother of Sofia and Bruno, author of The Precipice of Love (published in Italian, “Il precipizio dell’amore”), a beautiful book of personal testimony.

Mariangela Tari: The disability of a child or a loved one requires a long journey of knowledge – a journey on a new road with unknown rules. The whole family goes on that journey, because when one child gets sick, the whole family gets sick. At the beginning, there’s only pain and disbelief; we are completely overwhelmed. The family breaks down between sleepless nights and searches for miraculous remedies that do not exist. We get drunk, we argue a lot, we think about an impossible future. There’s a fear of being alone. Bureaucracy encroaches on everything, from school to the hospital to finding medication and helping with treatment. This time of great confusion is actually a time of learning and metamorphosis. You get to know new realities, parents who’ve been there before, and volunteer associations. You just need to have the ability and the will to search while everything is falling apart. When you suffer a lot, everyone contributes their own resources.

How do you deal with this suffering on a daily basis?

Of course, the suffering is there. I need daily help from others and from myself to understand what I suffer and why: desire, anger, pain, fear … I need to feel these things, to understand them, and to do something about them, because when I know what I’m suffering, I also understand that I can work through these emotions with practice. Doing, acting, is the first remedy.

I have to say that cancer, unlike disability, points you right to death. Cancer incinerates everything. It scares you, and it takes away all possibility to think about life. Cancer suddenly reminds you that life can end. Millions of people die around us every day, but we think of ourselves as immortal. My son’s tumor catapulted me into the present, into the here and now. So everything that for the rest of the world would just be bad luck, for us became everything we had.

What exactly does that mean?

Our kisses became stronger, our hugs more intense; the movie time we had on the couch became moments of indescribable happiness. Everything became focused on the present, sharpened and enlightened by the knowledge that life is made up of happy moments, happy incidents that we must welcome.

As a family, we’ve rediscovered the usefulness of useless things, being together with the people we love, living without hurrying, giving time to our children. We’ve created an archive of happiness made of few things, without thinking about the future. And finally, we gave meaning to something that had no meaning. We started to help others through an association called La Casa di Sofia (“Sofía’s House”).

Where do you get your strength? Where does it come from?

I don’t know where it comes from, but it amazes me every day. I think it comes from an attitude of wonder. Keeping open the question about life and wonder puts me in a state of almost childlike happiness. I still have so much to discover, and so many questions to ask the world.

Secondly, my strength certainly comes from the love I have for my children. I love them in an indescribable way. They’ve transformed me. They allow me to come out of myself and give of myself.

But strength also needs to be nourished. I have to remember that in addition to the person I’m caring for, there’s also “me.” Like when we get on an airplane and are told that if there’s a problem, we have to put our own oxygen mask on first, then put it on other people who are in trouble. We need to understand that we’re parents but also people. It’s essential to take small moments to be alone. This is very difficult to do: family caregivers don’t have free time. So we have to dare to ask for help, to shout this plea, not to be ashamed. Because you’ll come back home with more strength.

Is it possible to be happy in spite of misfortunes?

Pain is part of life. This is the first point. No one is immune to pain. And you don’t have to have cancer to suffer. It’s the human condition. So it should be treated exactly as we treat other things that happen to us. Listen to our suffering, cry all the tears we have when we need to cry, without fear; talk about it without shame. Then, pain also allows us to rediscover who we are, because it resets our knowledge.

Pain does what love does: it dislocates you, it puts you in a crisis, and a crisis means reformulating your judgment about the world. If you look at it that way, pain means possibility. Rejecting it is useless; it is stronger than we are. So we have to give ourselves time to suffer, to retreat until our own nature asks us to open up again.

In your book, you write, “It was pain that made me the strongest loser.” What does that mean?

When I had my first child, I was a teacher. As a teacher, I began to see my daughter beyond the disease. I wondered what she could learn, what she could be beyond Rett syndrome. In fact, I was looking at my daughter, not the disease. That’s why it’s our duty to help those who don’t have the tools. Disability is only a burden for a blind and individualistic society. As parents, at some point we looked for not a miracle cure but for activities and tools to try to make Sofia happy. It’s not easy; it’s very tiring and, among all the attitudes we start to cultivate, it requires acceptance. Accepting change and recognizing that it’s the only constant in our lives. And instead of letting ourselves be carried along by events, thinking that we have no power over a destiny that’s already written, we must decide, by making a pact with ourselves, that we can change the narrative.

But how can we change this narrative of misfortune?

We can “make pretend.” This is something I learned in drama class in school. We can pretend to have chosen this life and live it from every possible angle. Accept that you will lose many connections, and build new ones. Accept that you have to suffer some days, and know that this pain will end. It always ends. Change your inner dialogue, talk to yourself in words of possibility rather than of destruction. We can do this if we go in search of readings and experiences that people have lived that have changed the narrative of misfortune. A misfortune can become something else.

You say in your book that pain and joy are not so opposite.

Whenever I face painful days, I always reflect. I think the past seems incredibly beautiful to me, just because it’s past, it seems full of pleasant events. Even the days of hospitalization, the days when I thought I wouldn’t make it, appear in my memory with positive anecdotes. This means that the painful present becomes a pleasant memory. Then I come back to the present, live and try to build something positive even on a bad day. I change my attitude. So there’s a lot of work of the spirit involved. Work that is reset when you meet people who see your children as unhappy children.

Are there things other people say that hurt you?

When I meet someone’s eye and they turn away from me, or when my daughter is called a “poor little thing.” It all stops when you don’t get invitations for birthdays or afternoons to spend together. Community is everything. I can work on myself but the other person has to be my ally. The words that disturb me the most are these: “You are heroes!” No, my husband and I are not. We are human beings. Heroes don’t need help.

What words would you like to say to parents in similar situations?

I’m almost afraid to give advice, so I’ll give just three tips. First, always ask for help. Then take action and contact all the associations you can: a world of possibilities will open up to you. Finally, delegate without guilt when your body is broken. Your children or the people you take care of need you, so you must find yourself.