Lenten Campaign 2025

This content is free of charge, as are all our articles.

Support us with a donation that is tax-deductible and enable us to continue to reach millions of readers.

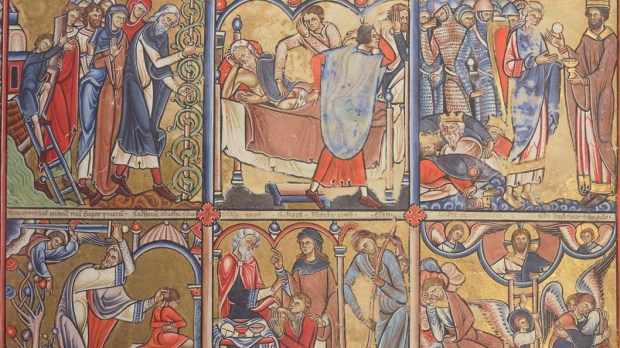

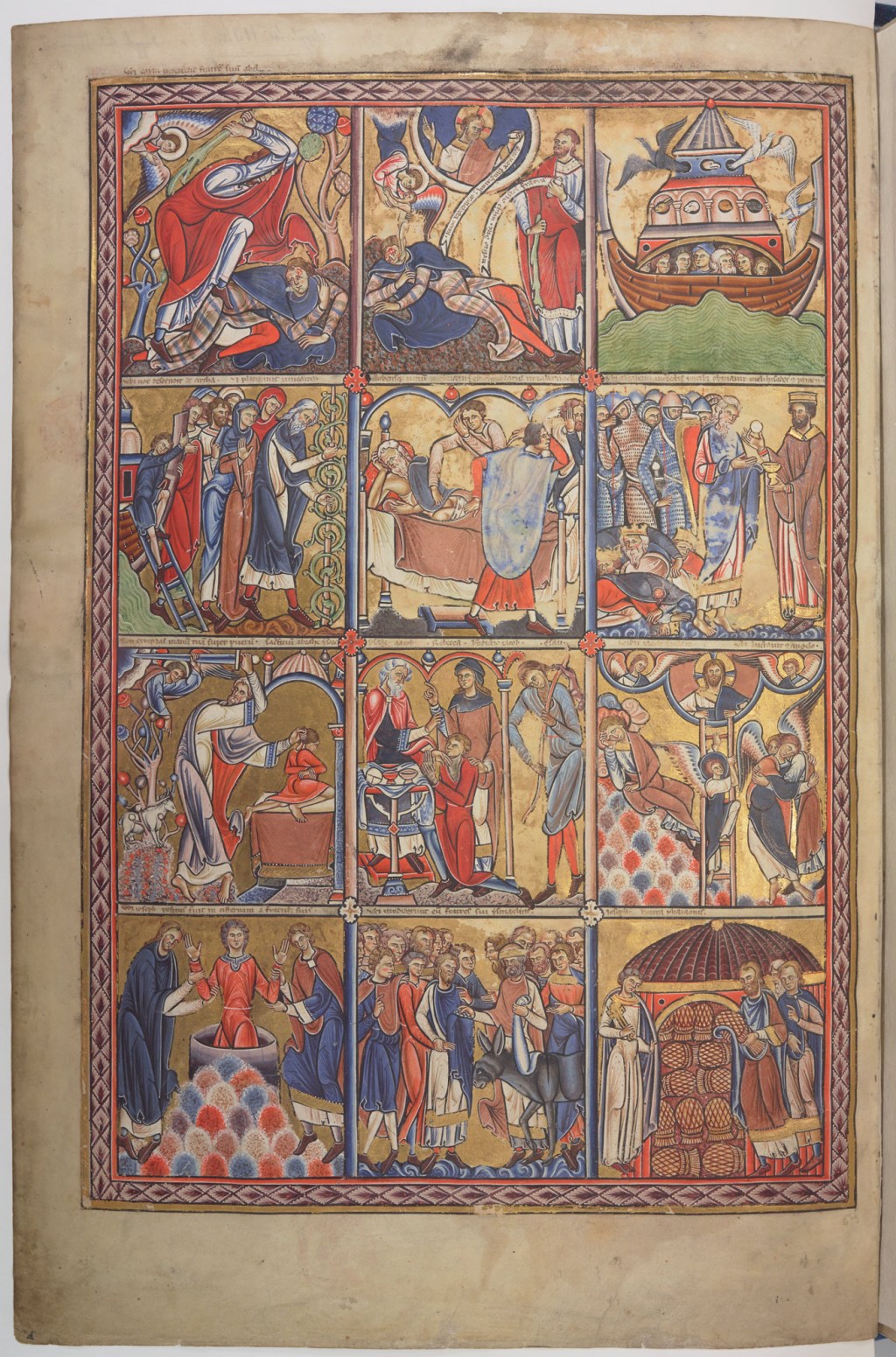

The Great Canterbury Psalter is an early 13th- and mid-14th-century illuminated manuscript. Undisputedly a masterpiece, it is the last of a unique series of psalters (all of them copies of the great Utrecht Psalter) linked to the Canterbury Cathedral, and the most important known work of the late medieval Catalan painter Jaume Ferrer Bassa.

Also known as the Anglo-Catalan Psalter, its folios feature only the first 98 psalms, all of them accompanied by a large header miniature. As Rosa Alcoy notes in her article for Medievalists.net, “46 of them are by English hands alone, 45 are the work of Catalans and 7 are combined efforts” – hence the nickname Anglo-Catalan Psalter.

The miniatures, Alcoy goes on, are in “virtually mint condition.” But it is the length, originality and complexity of the motifs employed to illustrate the psalms that make this manuscript an artistic landmark. It also has the merit of “featuring the figurative reality of two different periods more than one hundred years apart on the same pages.”

The Psalter was made in two locations, in two different moments in time. The first part of the work was made in Canterbury around 1200. It was finished more than 100 years later in Catalonia, around the year 1340.

The unexpected convergence of two traditions

In 1170 Thomas Becket (Archbishop of Canterbury) returned to England from his exile in France. He brought with him a series of splendid manuscripts. These acquisitions deeply influenced the style of the scriptoriumat the monastery servicing Canterbury Cathedral, which was by then one of the most important centers making illuminated manuscripts in England.

The monastery’s workshop embarked in an ambitious project: a triple Psalter, featuring the Latin, Hebrew, and Gallican versions of the Psalms – the Canterbury Psalter. Glosses in Norman French (the French dialect spoken in England for three centuries following the Norman conquest) were also added to the Psalter, as this was the preferred language of the court and the upper classes.

The monks made an impeccable copy of the text (there are no signs of any mistakes or corrections in the whole psalter) and illuminated the first part of the codex. The spectacular nature of the project and the abundant use of gold suggest it may have been a psalter for a king.

But the English miniaturists’ work was interrupted, preventing the Canterbury masters from completing the meticulous illumination work they had undertaken. Alcoy says that “a variety of events and circumstances caused the delay and consequently the remarkable and unexpected convergence of English illumination of the closing decades of the 12th century with the Catalan, Italianate tradition of the second quarter of the 14th century.”

Peter IV of Aragon was crowned king of Aragón in 1336. Bassa had already returned to Catalonia after studying in Tuscany, where he had been in contact the workshops, artists, and craftsmen of the early Italian Trecento.

He produced several works commissioned by the king (he had already worked for the crown of Aragon under Alfonso IV) in his Barcelona workshop. A splendid, unfinished English psalter came into his hands, including the sketches for seven miniatures and allocated blank spaces. It is highly likely that the crown asked Bassa to complete this psalter.

The seven paintings drawn by the Canterbury masters and painted by Bassa a century later are “the result of a unique combination of the Anglo-Byzantine culture close to the 1200 and the pictorial forms of the 1300 Italianate Gothic. They constitute a remarkable fusion of cultures,” Alcoy concludes.