Italy, 510. Benedict has been walking for several hours now, his eyes empty and his thoughts bitter. A few meters further on, between rocky and perilous slopes, the monk found the cave in which he had lived as a hermit for three years. If he is relieved to find his improvised cell, where he feels closest to God, his heart is still heavy with sadness.

After having refused many times to take the place of a deceased Father of the Vicovaro community, Benedict had finally given in. But as soon as he arrived, he realized that he had been chosen for his reputation as a holy man and that the monks were living too comfortably, enjoying alms and forgetting asceticism. And in trying to straighten out the corrupted morals, his brothers had tried to poison him. Wounded, Benedict had left Vicovaro.

By choosing God, should not the monks observe poverty, obedience and humility? How did his brothers come to poison their fellow man in order to preserve material comforts that have no value for the life of the soul? How can one so quickly forget the sacrifice of God for mankind? Benedict weeps loudly and offers a prayer for the debauched monks.

Manual labor as a path to humility

Some time later, when Benedict had resumed his life as a hermit, he found a young monk outside his cave, out of breath. Benedict asks him what he is doing here.

“Master, make me your disciple and teach me the life of prayer!” he begs.

Benedict blessed the young monk but sent him away. The next day, three other monks came to him. The next day, there were twenty. The following week, a group of a hundred monks came to the grotto. The number of requests continued to grow. Benedict finally accepted, seeing in their supplication the will of God. He settled down near the lake of Subiaco with his disciples.

Benedict divided the monks into twelve groups of thirteen. For Benedict, the watchword is “balance.” If asceticism is an important part of monastic life, manual work must not be forgotten. There is no better way to find humility. Especially in a time in history when manual labor was often left to slaves. If there is one thing Benedict disapproves of at all costs, it is excessive penance and mortification.

“It is not my place!” protested one of the monks who came from the aristocracy. “I cannot stoop to that.”

“Is your pride more important than God? In that case, go away!”

The other monks follow Benedict with gusto. The little community shines and delights the people of the area, who abandon the local churches to attend the monks’ Masses. Jealousy made the priests of the region try to slander the monks. Benedict even escaped being poisoned a second time. After about twenty years, the malicious attacks were such that the monks decided to leave Subiaco around 529.

The masterpiece of the Benedictine Rule

Benedict led his disciples to Monte Cassino, where there were the remains of a pagan temple dedicated to Apollo. The monks quickly broke down the idols and began work on the new monastery. Around 534, Benedict began to write the Rule.

A simple phrase guides it: “Ora et labora”. The balance that Benedict seeks is a perfect harmony between prayer and work. The Rule also allows the monastery to be self-sufficient, since the monks work the land. Benedict warns the monks against excessive mortification.

“Servants of God are to fast often and never abuse the good things, but not to neglect the necessary.”

Monks should renounce worldly living and observe obedience, humility, piety, silence and poverty. Prayer times are shortened because, according to Benedict, length is not synonymous with quality. A revolutionary thought for the time! He insists that fervor and goodness of intention are far more important. Thanks to this new thinking, there is an infinite gentleness in the monastery of Monte Cassino.

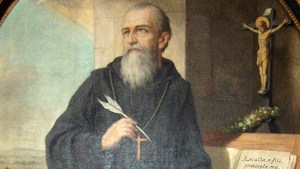

Benedict died in 547 at Monte Cassino. In his desire to find a model for a life that is at once humble, rigorous and simple, St. Benedict came to write the Rule that still serves as a model for many consecrated persons today.