The Crusaders fighting the troops of Saladin may have had the upper hand thanks to their diet. A group of scientists specialized in extracting traces of protein from archaeological and historical objects in general found significant differences between the pottery used by the Crusader forces led by Richard the Lionheart, and those used by soldiers loyal to the sultan Saladin during the Third Crusade (1189-1192). In short, Crusaders kept fit by sticking to a relatively keto-ish diet.

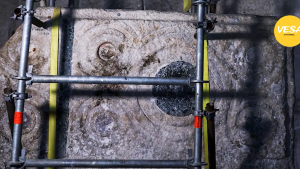

According to the scientific article, published in Heritage Science Journal, the analysis of food remnants “confirmed that the Crusaders’ diet consisted mostly of pig and sheep meat (together with cheese), with a minimum of carbohydrates (what today would be termed a “ketone” diet) whereas the Muslim army consumed mostly carbohydrates (wheat, triticum durum, hordeum vulgare), together with fruits and vegetables, with minimal levels of sheep meat and cheese.” The scholars then suggest that this difference in dietary habits meant that the Crusaders were slimmer (more “cardio”) than their Muslim counterparts, which might help explain why some historical accounts of the famous battle of Arsuf claim that Saladin’s army lost 10 times as many soldiers as Richard the Lionheart’s did.

The Battle of Arsuf place on September 7, 1191. It ended up in a Christian victory, after the forces led by Richard I of England, The Lionheart, defeated a larger Ayyubid army led by Saladin.

According to some accounts, the battle took place just outside the city of Arsuf, when Saladin met Richard’s army while moving from Acre to Jaffa, following the key Crusader capture of Acre by Guy de Jerusalem. During their march from the city, Saladin launched a series of unsuccessful attacks on Richard’s army. As the Crusaders crossed the plain to the north of Arsuf, Saladin sent the whole of his army into battle. The Crusader army kept a defensive formation while still marching ahead, waiting for the moment to mount a counterattack. The Knights Hospitaller launched a charge at Saladin’s troops, and Richard was forced to support them. Once he managed to regroup his army, victory followed. The battle resulted in Christian control of the central Palestinian coast, including the port of Jaffa.

As the scientists in charge of the study claim, “shrewdness of leaders, soldiers’ equipment and willingness to fight are of course the main ingredients of victory.” But “diet too might not have a secondary role and help to tip the balance.”

Now, not all specialists agree that diet might have played even a secondary role. As read in an article published by Jack Malvern in The Times, Suleiman Mourad, co-author of Muslim Sources of the Crusader Period and a professor of religion at Smith College, Massachusetts, said this new information would surely help understand the world the Crusaders lived in, but would not explain why or how they won battles. In fact, professor Mourad noted that historical sources were ambivalent about whether there was a significant battle at Arsuf at all. Accounts of the events found in the Near East suggested that each side avoided prolonged battles after the Crusaders captured Acre, betting on rather small skirmishes to avoid the kind of full-on attacks that could end in a decisive defeat.

“The strategy of both parties was not to engage in a full-fledged battle that would destroy them,” he added. “The minute the Crusader army made the charge at Saladin, most of Saladin’s army took flight and Saladin had to stand his ground until his soldiers returned. The soldiers ran approximately a mile. Some sources say that there was nothing there, not even a battle,” professor Mourad told The Times.

A strict, healthy, powerful diet

Be that as it may, the truth is that Crusaders often lived past the age of 60, which was rather exceptional in their day and age. These researchers believe their longevity can be explained from their rather uncommon Crusader diet. For example, Jacques de Molay, the order’s final Grand Master, was executed when he was already 70. Geoffrei de Charney, who was also executed in the same year, is said to have been around 63. This longevity seems to have been almost commonplace. As Natasha Frost rightly points out in her article for Gastro Obscura, “fellow Grand Masters Thibaud Gaudin, Hugues de Payens, and Armand de Périgord, to name just a few, all lived into their sixties. For the times, this would have been positively geriatric.” Modern research suggests that the Order’s strict dietary rules may have contributed not only to their military success, but also to their long lives and good health.

It was St. Bernard de Clairvaux who helped create the Primitive Rule of the Templars, based on both the Rules of Augustine and Benedict but also on practices that were already existing in the Order way before the Rule was finished. Frost goes on to explain that “the knights were to protect orphans, widows, and churches; eschew the company of ‘obviously excommunicated’ men; and not stand up in church when praying or singing […] habits were one color alone, though on warm days between Easter and Halloween, the rules decreed, they were allowed to wear a linen shirt.” The rules, of course, also determined how, what, when, and with whom they ate.

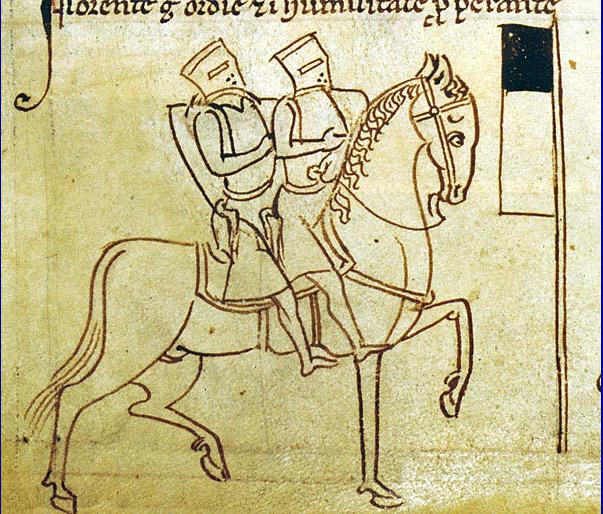

The knights’ emblem showed two men sharing a horse. In a like manner, they were meant to eat together, silently, even sharing bowls, making sure everyone ate their fair share; no more, no less. Their diet was a delicate balance between the kind of fasting and abstinence one would expect from monks, yet with the added protein that active, military life demands, somewhat similar to the diet Jesus himself probably kept, which allowed them to stay fit. They were allowed to eat meat (basically roasted animals, including ham or bacon) on Tuesday, Thursday, and Sunday.

On Mondays, Wednesdays, and Saturdays, Frost explains, the Crusaders’ diet included “more spartan, vegetable-filled meals. Although the rules describe these meals as ‘two or three meals of vegetables or other dishes eaten with bread,’ they also often included milk, eggs, and cheese. Otherwise, they might eat pottage, made with oats or pulses, gruels, or fiber-rich vegetable stews […] In their gardens, they grew fruits and vegetables, especially Mediterranean produce such as figs, almonds, pomegranates, olives, and grains. These healthy foodstuffs likely also made their way into their meals.” Fridays were reserved for a kind of Lenten fast, consisting mainly of salted fish and almond milk.

Make sure to visit the slideshow below to discover seven healthy foods Jesus ate.