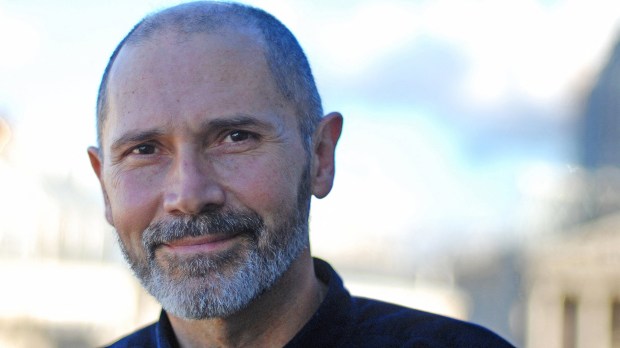

When he was struck by a serious illness six years ago, famous French psychiatrist Christophe André realized his immense need for consolation. “When I was carried on a gurney between different hospital departments, anxious and fragile, a small gesture such as a hand on the shoulder or a kind word to tell me that it was going to be alright made me feel good,” he says.

That’s when he discovered the beneficial power of consolation. It allows you to stand up to the hostile realities when they appear, and not to sink into grief or despair. It is also an “act of loving presence that puts us back in touch with the world.” I spoke with him for Aleteia about his thoughts on this topic.

Aleteia: You say that for a long time you were blind to consolation. You were content with “caring, encouraging, comforting, but not consoling … And it was when you became seriously ill that you opened your eyes to consolation.

Christophe André: Yes, six years ago, I had lung cancer. When I was told about it, everything fell apart in an instant: I went from the world of the healthy to the world of those who are different and fragile. I was sad to think that my life would be shorter than expected. It was then that I realized that I needed consolation.

So, you have experienced the benefits of consolation in your own sick body …

Every time a caregiver saw me in distress and made a small gesture to console me, I immediately felt the biological benefit of consolation. I thought to myself that if we were just cared for by robots, something would be missing, even if they were doing their job perfectly. Every time someone offers a gesture of consolation or comfort, we feel better, and every time they don’t, we feel worse. I felt it physically in my body.

He was a former patient of mine from Toulouse. He was a drug addict and suffered from bipolar disorder. I was having trouble treating him, but he kept coming back to see me; he didn’t want to see another doctor. As I looked back on our sessions, I realized that I wasn’t able to cure him, but I was able to console him almost every time … and without my knowing it!

Healed and back home after your hospitalizations, you found a signed note from one of your patients. He thanked you for your patience and the great trust you showed him during your sessions. Had you comforted him without knowing it?

Of course, as a doctor I was always kind, benevolent, and warm to my patients, but I was mostly thinking about the technical aspect of care. I wanted my patient to get well. I didn’t understand at the time that there was another beneficial experience besides science and kindness: that of consolation. My illness allowed me to discover its power. And I wanted to explore it, because we are constantly in contact with it. At one time or another, we all need to be comforted.

How can we console someone well?

To console is to wish to relieve pain without being able to modify reality. Consolation is not a search for solutions, but it allows us to lighten the feeling of suffering. It does good. It’s a help for the inside and not for the outside. This means that beyond the concrete dimensions of words and gestures, it’s above all a process without visible results. As such, it can be said to be immaterial and spiritual. Consolation often begins with our presence, with an intention, with very simple gestures and words.

Why is it sometimes so difficult to console someone?

When I was writing my book on consolation, many people told me that they were uncomfortable with consoling others. Faced with another person, whether sick or bereaved, we’re afraid of hurting them, of making a mistake that would make their grief even worse. We can even be paralyzed by suffering, or be overwhelmed, as is often the case with me, by our own emotions.

If there’s one golden rule, it’s to take your time, to go slowly, to be satisfied with small things at first: just say: “I’m here,” “I’m thinking of you,” or touch their arm, take their hand … Not long ago, a friend of mine experienced an inconsolable tragedy—the loss of her child. I didn’t know what to do or what to say to her. I just wrote her a text message: “Thinking of you, giving you a hug.” She told me some time later that those simple words had helped her. My text seemed small in comparison to her immense pain, yet it gave her some comfort.

You emphasize that we must be careful not to impose ourselves while trying to console. Why is this?

We often forget this, but consolation is in itself an intrusion. Imagine for a moment a person locked up in their grief: even if it’s an imprisonment that hurts them, they are locked up in their own grief. So, we arrive, and we try to knock on their door. Then we come in, we see them in a dark room with closed curtains and their head under the pillow. A consoler’s reflex would then be to open the windows, let in the light, remove the pillow and encourage the person to get up. But in the end, all of these actions may disturb the person. So, before doing anything, it’s essential to ask the person’s permission to approach them and stay by their side. Consolation is not performing a repair, but offering support. It’s not about being efficient and finding solutions to the other person’s difficulties.

In this delicate alchemy, it is almost necessary to arrive without the intention of consoling (“Here, you’ll see, I’m going to console you!”) and to say to oneself: I’m going to approach gently, to try to understand what the person needs, to do very simple things by saying: “I’m here,” “Can I help you?” Or leave, if the other person doesn’t give permission to accompany them for the moment. Once again, humility, simplicity and gentleness are the qualities of the art of consoling, in which the tenderness of the one who consoles and the acceptance of the one who is consoled are required.

Are there situations where consolation is impossible?

Parents who have lost a child are always inconsolable. When I talk to them, they all tell me that there is a part of them that died that day, and that will remain dead forever. They will never be consoled. And while that part of them will remain wounded forever, what I try to do is to reconnect them with the world. These parents often have other children, so they have to live for them. They also have to know how to live well with the memory of the missing child. This is often a great motivation for them: to keep the memory not of the child’s death, but of his life. It’s very consoling. But it takes a long time for this to emerge in the minds of grieving parents.

You say that faith consoles. You write: “When I pray, I have the strange feeling that I am calling God …”

Like most people, God has never spoken to me directly. But I often have little hunches that I am not alone. I love this phrase from Paul Claudel: “God did not come to remove suffering. He came to fill it with his presence.” Yes, there is indeed something that happens when I pray. It’s as if, at the end of the phone, I hear someone breathing and listening to me in silence. There are no words. There’s just this presence. I, whose faith is wavering, observe that each time I surrender to Him, I feel better, calmed.

We are currently going through a collective trial with the war in Ukraine. Is it possible to console a country, an entire society?

A few days ago, I participated in a special edition of France Inter on Ukraine. There were a lot of listeners who were calling in live to ask how to help the Ukrainians. Some suggested organizing demonstrations and petitions; others, putting Ukrainian flags on social networks. And at one point, I said to myself that all these actions were so derisory compared to the situation: the conflict is going to last and get even worse … However, we all have the intuition that for the Ukrainians, all these signs are signs of consolation. They see that they are not abandoned.

Here again, we are at the heart of consolation. Even if we cannot prevent adversity, we say to ourselves that we cannot leave all these people alone. I think that if I were Ukrainian, knowing that the whole of the West supports Ukraine and is putting pressure on Russia to back down, would console me a little. Even if it doesn’t solve anything, it’s important for Ukrainians to know that the rest of the world is thinking about them. I believe that this consoling outpouring of support can turn their hope into confidence and strength. And again, consolation cannot prevent misfortune from happening, but it is a remedy. Consolation is one of the most beautiful faces of love.