There are a few things that symbolize “Christmas” all around the world. In many countries, people trim trees, celebrate with Christmas carols, and create intricate Nativity scenes to herald the coming of the baby Jesus.

But to Italians, Christmas would not be the same without Panettone, the iconic dome-shaped Christmas cake. Dating back to Roman times, this soft, sweet loaf cake stuffed with raisins, nuts and candied fruits owes much of its development to Catholic figures.

We know from historical evidence that ancient Romans used to bake a type of leavened bread (panem triticum) with eggs, honey and raisins for celebrations. But it’s not until the Renaissance that we have proof of a Panettone recipe akin to that of contemporary patisseries. Sixteenth-century cookbooks by Bartolomeo Scappi, a chef who served Pope Pius V, show that a loaf cake filled with raisins was part of the refined menu he put together for the Head of the Church. Panettone, made up of the words “panetto” (loaf) and “one” (big), was also featured in a 16th-century painting by Pieter Brueghel the Elder.

Thanks to these historical clues, we know that an ancestor of today’s Panettone was common during the Renaissance. But when did it become a Christmas cake? As with many iconic foods, legend and myths have developed about the origin of Panettone as a Christmas cake. The most popular legend has it that Panettone was invented on a Christmas eve of the 15th century at the court of Ludovico il Moro in Milan. The chef had prepared a Christmas pudding that got burned. But the dinner was saved by the ingenuity of a servant, Toni, who stuffed a loaf of bread with raisins, sugar and nuts. Ludovico il Moroliked the bread so much that he called it “Pan de Toni” (bread of Toni).

Whether true or not, the legend seems to be rooted in some reality. Thanks to records kept by a Catholic boarding school, the Borromeo school of Pavia, we know that by the 1500s Panettone had become a Christmas tradition.

Founded by Milanese Cardinal Saint Carlo Borromeo in 1561 and defined as “the palace of knowledge” by art historian Giorgio Vasari, the Borromeo College hosted promising students of disadvantaged backgrounds. Students were housed and trained by Catholic priests and professors and many notable theologians, doctors and lawyers graduated from this school. The meticulous records kept by its administrators show that in 1599 students were served a “Christmas bread” made with butter, raisins and spices.

Moreover, records dating to the 16th century show that Milanese bakers used to make Panettone in the weeks leading to Christmas. Breaking from the traditional habit of baking white bread for rich customers and millet bread for poorer ones, Panettone was distributed to rich and poor alike.

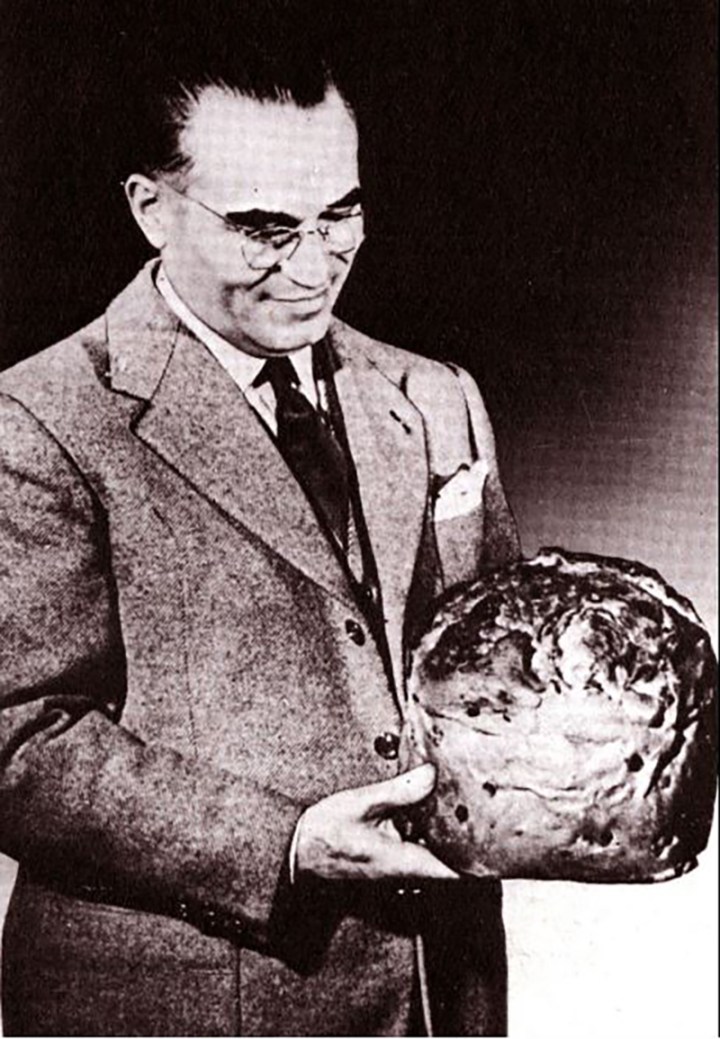

During the 18th century, Panettone was named by Pietro Verri as a typical Christmas tradition in his “History of Milan.” But it wasn’t until the 1920s that the famous cake got its current dome-shaped look. We owe that to Milanese baker Angelo Motta, a member of the The Equestrian Order of the Holy Sepulchre of Jerusalem, who mimicked the kulic, a traditional Russian cake usually baked for Easter.

Today, as many as 54 million Panettones are bought during the holidays in Italy alone, and Pope Francis has become a fan of the tradition. Since his papacy began in 2013 he has been receiving a special Panettone, created for the pope by Sicilian chef Nicola Fiasconaro. It is baked with “manna,” the famous biblical substance found in the bark of ash trees.