Between Election Day and Inauguration Day, much attention in New York City had been given to the soaring heights of Trump Tower, whose chief resident was welcoming high-profile visitors to his opulent suite, vetting them for administration posts.

Meanwhile, just a few blocks away, officials at St. Patrick’s Cathedral were quietly and humbly preparing for a small miracle deep beneath the ground.

In mid-February, the Archdiocese of New York announced that the historic cathedral, which has undergone a $177 million renovation over the past four years, activated a geothermal plant to heat it in winter and cool it in summer.

The minor miracle is the way they can now transform God’s gift of water into a comfortable atmosphere for the tens of thousands of visitors who pass through the cathedral doors each year, as well as clergymen and lay people who live and work in the iconic church’s adjoining buildings. That would include Cardinal Timothy Dolan’s official residence and a separate house for the cathedral’s parish priests.

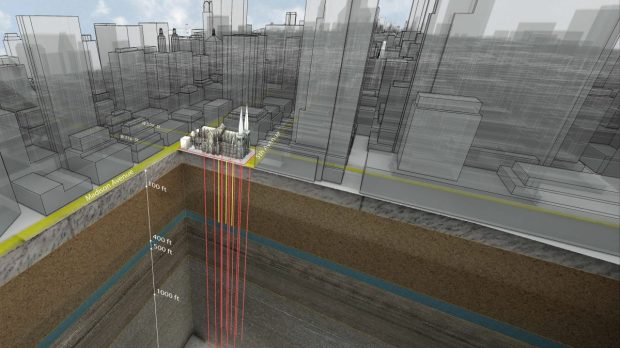

In order to heat or cool the structures, engineers had to drill 10 holes into Manhattan’s bedrock on the outside periphery of St. Pat’s, between 600-2,200 feet, to tap into ground water that, no matter how frigid or how broiling it is on New York’s streets, maintains a fairly constant temperature, between 52-63 degrees.

For sake of comparison, the greatest depth — 2,200 feet — is more than the height of One World Trade Center, or the Freedom Tower — which is 1,176 feet tall.

“The basic principle is that you’re extracting water from the earth, and in the wintertime you’re pulling heat out of that to create heating for the building, and in the summer you’re pulling cooling out of that water and injecting the hotter water back down into the earth,” architect Jeff Murphy explained. “So it’s giving you a higher basis of energy, whether it’s cooling in the summer or heating in the winter.”

Murphy’s firm, Murphy, Burnham, & Buttrick, the cathedral’s design team, worked with PW Grosser, who developed and repurposed the existing infrastructure to harness clean, renewable power from the underground system of wells.

The pumped-up water is sent through one of six heat exchangers that were installed underneath the cathedral. The heating that is extracted is then sent to air handlers and fan coil units that deliver it as needed.

In warmer months, the system will “extract excess heat from the cathedral and pull it into the ground, where the earth absorbs it, serving as a heat sink,” said Mercedes Lopez Blanco, a spokeswoman for the archdiocese.

Reducing carbon emissions

There are very few structures that have geothermal heating plants in the Big Apple, so not much else gets down to the depth of these wells. Other institutions using geothermal technology include Union Theological Seminary, the Brooklyn Children’s Museum, and the Queens Botanical Garden.

The cathedral’s new plant will be able to generate 2.9 million BTUs per hour of air conditioning and 3.2 million BTUs per hour of heating, servicing a total of some 76,000 square feet in the 136-year-old church and adjacent buildings.

Neither Lopez Blanco nor Murphy had specific figures on how much money the new system is expected to save the cathedral, but the architect said they think they have reduced the use of energy needed to heat and cool the church by about 35%.

What Church administrators are crowing about, though, is the way the system will considerably reduce CO2 emissions.

“A consistent ethic of life … prioritizes life and the preservation of life at every level. One of the most basic ways in which we are called to do so is through responsible stewardship of our natural resources,” said Msgr. Robert T. Ritchie, rector of the cathedral. The archdiocese hopes its move will encourage business leaders and institutions to also consider renewable energy solutions.