Much has been written about the troubling and revealing remark made by California Senator Dianne Feinstein to Notre Dame Law School Professor Amy Coney Barrett, who has been nominated by President Trump to the federal judiciary.

Feinstein said, “When you read your speeches, the conclusion one draws is that the dogma lives loudly within you, and that’s of concern when you come to big issues that large numbers of people have fought for for years in this country.”

In short, Senator Feinstein advanced the notion that a Catholic who is committed to the faith (as opposed, presumably, to one who dissents) might not be suitable to public office because their religious dogma would collide with established secular and political dogmas. Feinstein is apparently irony-challenged. I like how Sohrab Ahmari, in a good op-ed at the New York Times puts it as he notes the senator’s illiberal message:

“…it isn’t enough to have won most of the cultural and policy battles of the past several decades. Even the remnants of the other side, in people’s minds and consciences, must submit to maximalist progressive claims… the desire to do so isn’t actually liberal. It is, well, dogmatic. Not all dogmas involve Almighty God.

Emphasis mine.

Senate Minority Whip Dick Durbin of Illinois — who is a Catholic, but apparently, in the eternal words of Archie Bunker, he is “one of the good ones” — used his time questioning Barrett to dredge up memories of the Army-McCarthy hearings. His asking Barrett if she was an “Orthodox Catholic” drew too many memories back to “Are you now, or have you ever been a communist?”

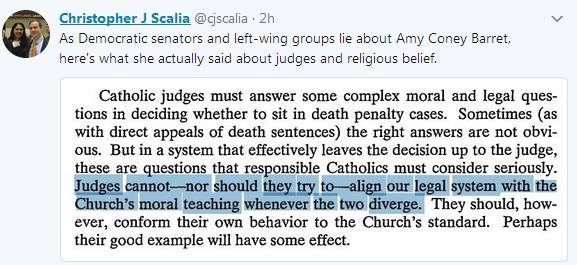

Durbin and Feinstein’s panic over dogma, by the way, seems to stem from a willful misreading and misrepresentation of Barrett’s own bottom line:

In all likelihood, Barrett will be confirmed to the post. Feinstein and Durbin knew that when they made their remarks. In this stubbornly divided nation, every nominee to every post must be subject to political theater for the sake of constituencies and the cameras (and Feinstein had just angered her base a week earlier and needed to do her penance), so some objection had to be found and noisily registered in the matter of Professor Barrett.

That Feinstein and Durbin chose to play the anti-Catholic card (a move which, as Salena Zito rightly reasons could kick them right in the rust belt, next election) suggests that there was simply nothing else about Barrett that could be used against her.

Or, it could be an unsubtle signal that, for some, practicing Catholics need not apply to any sort of public office, because they cannot be trusted to be real, faithful Americans, over servants of Rome. One fears a creeping (or galloping) resurgence of “Know-nothingism” and coming — in yet another irony — from the very faction that once resisted it.

Historian Pat McNamara gives us the background on “Know-nothings”:

On the night of April 6, 1844, a mob of white Protestant males calling themselves “Native Americans” marched toward a Roman Catholic Church on Brooklyn’s Court Street, intent on burning it to the ground. […] From the 1830’s through the 1850’s, such scenes were duplicated in nearly every major American city where immigrants gathered in large numbers… In Massachusetts and Pennsylvania, convents and churches were burned to the ground. From Kentucky to Maine… anti-Catholicism had reached a fever pitch in American life, unseen before and perhaps since.

Do read the whole thing. As McNamara notes, the group’s demise didn’t mean the end of anti-Catholicism, which historian Arthur M. Schlesinger, Sr. called the longest reigning prejudice in American history.

A good deal of the Know-nothing’s energy came from anti-immigration sensibilities, and one reason it died out was because, as McNamara writes, “With Catholic immigrants shedding their blood in defense of the Union, it seemed ludicrous to question their patriotism.” To our modern ears, the jingoistic “Know-nothing” claptrap — and the many anti-Catholic op-eds and political cartoons in its support — echos the nativism of the farthest extremes of the alt-right, or might be thought akin to the rhetoric surrounding “Brexit” in the UK.

It helps to recall that the public service ambitions of people of faith have been on the shoals for a while. Former Prime Minister Tony Blair was told by his own government “we don’t do God”, shortly after 9/11. He waiting until he was out of office to become a Catholic.

Right now in the United Kingdom Jacob Rees-Mogg, a Member of Parliament who seems to enjoy living his Catholic dogma as “loudly” and flamboyantly as possible has been denounced as a bigot unfit for any sort of public office.

For all I know, he might be a bigot — it’s not unheard of for people to use their religion as a license to be uncommonly nasty — but I don’t know enough about Rees-Mogg to guess. He could be every bit as bad as they say, or he could be a “dogmatic Catholic” who — because the Church and our pontiff both recommend it — nevertheless intends on creating an atmosphere of dialogue and true accompaniment.

Either way, the troubling queries made to Professor Barrett, roundly decried among US Catholics, whatever their political leanings, and the downright ghastly and uncharitable political cartoons that are taking off on people of faith should give us a bit of a heads up — that it pays to hear and heed our history, so it needn’t repeat itself.