Lenten Campaign 2025

This content is free of charge, as are all our articles.

Support us with a donation that is tax-deductible and enable us to continue to reach millions of readers.

In July 2016, Dallas Police Chief David Brown and the city he loves endured an unforgettably horrific day. Seeking revenge for the deaths of unarmed black men at the hands of white police officers in other parts of the country, a sniper murdered five cops before being killed himself.

As an African American and a 33-year police department veteran, a heartbroken Chief Brown navigated the aftermath of that tragedy with strength and grace, bringing healing to broken families and comfort to a wounded nation. He was only able to do so because of the trials he himself had endured over the course of his life – and a long-ago act of kindness that changed his view on race relations.

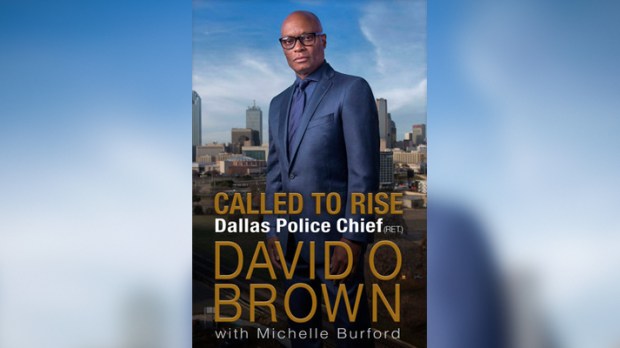

During an interview about his memoir “Called to Rise,” Chief Brown recalled growing up poor in a “black neighborhood in Dallas.” His mother, Norma Jean, emphasized the importance of education, so she made sacrifices to send him to a private Catholic school for pre-K, kindergarten and first grade.

That decision, said Brown, set him up for academic success that eventually included a full scholarship to the University of Texas in Austin: “The nuns made sure you were at grade level with reading – and then we got above grade level…They structured [school] in a way where getting behind or misbehaving wasn’t accepted.”

As a result of desegregation, Brown was bused to an all-white public school in 1971 when he was in sixth grade. After growing up surrounded by predominantly black children and adults, this was a completely new experience that, initially, left him with a bad taste in his mouth.

“No one speaks to me,” said Brown. “I’m looked past as if I don’t exist. That was my first introduction to how whites treat me differently.”

A few months later, Mike Shillingburg entered the picture: “He’s a popular white kid in my class. One day, Mike decided to invite me home for dinner after school. He and I became friends. His mom was real nice to us. We ran for class president and vice president, and we got elected. All the other white and black kids begin to interact more and become friends. That one act of kindness that you think doesn’t mean a lot, it changed everything about my views, especially about race and people in general.”

The impact of kindness and getting to know people as human beings instead of judging them by the color of their skin also worked its way into Brown’s police work. He joined the department in 1983 because he wanted to fight the crack cocaine epidemic that had taken hold of his old neighborhood. “Let’s put ’em in jail and let God sort ’em out,” was his attitude.

Eventually, Brown was reassigned to a community policing unit in a housing development. The unit required officers to get out of their patrol cars and interact with the people in the neighborhood.

“I’m thinking it’s a waste of time,” said Brown, “until I bump into someone that reminds me of my great-grandmother Mabel. We talked and became friends, and I got introduced to her family. They have been existing in this housing development because of generational poverty since it began…These people have made a connection with me, because I’m from poverty. There but for the grace of God go I.”

Brown started rethinking his opinion on community policing and asking himself how cops could make positive connections while still making the neighborhoods they patrolled safer.

He said, “In my opinion, community policing has a simple definition: it’s interaction with people when there’s no crisis in order to build trust. It’s hard to use excessive force on someone you’ve met and [with whom] you have a relationship. It’s hard to think about using your firearm when you know their family and the kids and grandkids. It humanizes and creates a connection that, I think, yields benefits downstream and makes not only the cops safer, but makes citizens safer. And it also reduces crime significantly more than the traditional mass incarceration the war on drugs did.”

As he moved his way up the ladder to become Police Chief, Brown supported and implemented those ideas with much success, including the lowest murder rate since 1930. In fact, not a single police officer was killed during his tenure as chief until the assassinations in July 2016.

“When you get the call that one officer’s down, then another – and you get that call five times in a span of five minutes, it shocks the soul. You feel there’s evil involved, and it’s going to take everything you have to confront it.”

But confront it, Brown did, largely because he was no stranger to tragedy. Years earlier, his son developed bipolar disorder and wound up killing two people before being killed himself. In addition, Brown’s brother was murdered by a drug dealer, and his first police partner, Walter Williams, was killed in the line of duty.

Williams’ death was the first major loss Brown experienced in his life, and it shook the faith in God with which his mother and great-grandmother had raised him. The Wednesday after it happened, he attended a prayer meeting at a local church. But he didn’t go to find spiritual sustenance.

“I go to tell the Lord goodbye,” recalled Brown, “that religion doesn’t protect us from these types of tragedies. So I was gonna quit, and I was gonna do it in church and walk out the door and leave. The older women in the church that were in that prayer meeting all got up and gave testimonies about how they had gone through tragedies and the Lord had sustained them. Person after person recounted their testimony to me. And then I came back the next Wednesday and the next Wednesday, and my faith was restored. I don’t know that I made a mental decision to stick with my faith. I think my faith wouldn’t let me go. When I wanted to quit, the Lord wouldn’t quit me. He would give me that reassurance, that grace and mercy, that unmerited favor to keep me going.”

Though Chief Brown is retired from the police department, he has found other meaningful ways to serve others and share his blessings. He is now a member of the ABC News team offering a balanced perspective about policing, race, and social justice stories. He also serves on the boards of foundations that help with mental illness, drug treatment, and early childhood education funding.

Because of the triumphs and tragedies of his life, Chief Brown believes in the Christopher ideal of lighting a candle rather than cursing the darkness. He concludes, “It has been the resonating theme in my life only upon reflection. When I’m going through the ups and downs and the ebbs and flows of life, it makes no sense…I would encourage people to reflect and look back at how they got through [challenges] and became better, how that helps them in another area of their life even though it was painful and negative. I think the purpose of our faith is that we will take our experiences with the Lord and be a benefit to somebody else. That was my policing for 33 years, and upon reflection, that’s been my life.”

(To listen to my full interview with Chief David Brown, click on the podcast link):