Lenten Campaign 2025

This content is free of charge, as are all our articles.

Support us with a donation that is tax-deductible and enable us to continue to reach millions of readers.

It started with a pocket watch.

In 1994, after my mother’s funeral, my sister, an aunt and I spent a few days in my mother’s apartment sorting through her things and dividing up what would go where. We came across a jewelry box, buried in a dresser drawer. I popped it open and inside was a small round object in a velvet bag. I looked inside; it was a silver pocket watch. Inscribed on the back were the initials: “Bro. J.” I showed it to my aunt. “Any idea where this came from?,” I asked.

She nodded. “That was your father’s,” she said. “I remember when he got it. They were gifts for all the brothers one Christmas.”

Now, I had known that my father had been in the Christian Brothers for a few years shortly before the start of the Second World War. But the details were always sketchy. “But why does it say ‘Bro. J.’?,” I asked her.

“That was his name,” she replied. “Brother Jerome.”

Well. I turned the watch over in my hand and processed that bit of information. Brother Jerome. I wound the stem. It began ticking. It still kept perfect time. I slipped it back in the velvet bag and stashed it away with my things. I wanted to keep it.

And I wanted to know more about the mysterious life my father had led back in the 1930’s. What was it like to be a brother back then? How did he live? And why was a man born “George” known for several years as “Jerome”?

And I wanted to know more about the mysterious life my father had led back in the 1930’s. What was it like to be a brother back then? How did he live? And why was a man born “George” known for several years as “Jerome”?

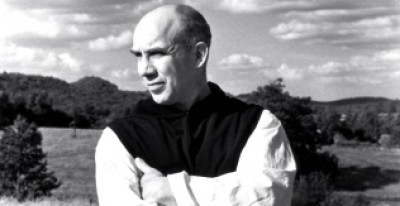

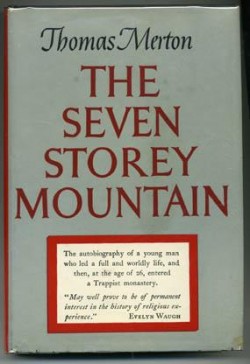

A few days later, over coffee, I mentioned the story of the pocket watch to my father-in-law, and he asked me if I’d ever read “The Seven Storey Mountain” by Thomas Merton. I told him no. He explained that he had read it in high school, back in the 1950s. It described this swinging young bachelor’s conversion to Catholicism and how he finally decided to become a monk. “He was even a communist for a while,” my father-in-law said. “It’s a great read.” I told him I’d check it out.

Well, he decided to make it easier on me. A couple weeks later, he sent me in the mail a paperback edition of “The Seven Storey Mountain.” Not long after, I sat down started the first page.

“On the last day of January 1915, under the sign of the Water Bearer, in a year of a great war, and down in the shadow of some French mountains on the borders of Spain, I came into the world. Free by nature, in the image of God, I was nevertheless the prisoner of my own violence and my own selfishness, in the image of the world into which I was born.”

I was hooked. I continued reading. And in some ways, I’ve never stopped.

Nearly 20 years later, the book remains a touchstone in my life, and I’ve read and re-read and marked up that copy of the book at least a dozen times. Every reading brings me something new, throws a bright light on some other corner of my life, and puts my own faith journey into context.

Now, I’m happy to see it’s been included in the compendium of “25 Books Every Christian Should Read,” now being discussed in thePatheos Book Club. Thomas Merton thus joins such lofty company as St. Augustine, C.S. Lewis, Blaise Pascal and St. Benedict.

Now, I’m happy to see it’s been included in the compendium of “25 Books Every Christian Should Read,” now being discussed in thePatheos Book Club. Thomas Merton thus joins such lofty company as St. Augustine, C.S. Lewis, Blaise Pascal and St. Benedict.

Why does Merton’s book have such a hold on me? Part of it, I know, is because his story is so modern and so relatable. I’ve told more than a few people: “Under only slightly different circumstances, that could have been me.” The book recounts how this jazz-loving, girl-chasing pseudo-intellectual hotshot was climbing the literary ladder and working on his Master’s at Columbia when he discovered, to his astonishment, the writings of William Blake. He began delving more deeply into the Catholic Church. In 1939, he converted, and two years later, he joined the Trappists – giving up everything to live in a world with nothing, embracing as he put it “the four walls of my new freedom.” He never thought he’d write another word again. But he did – beginning with the story of his conversion, “The Seven Storey Mountain.”

The book became a sensation – the first religious book to hit the New York Times bestseller list – and spawned hundreds if not thousands of vocations in the 1950s. I am convinced it also helped ignite my own vocation to the diaconate, spurring me to discover more writings by Merton and take some private retreats at Trappist monasteries, where I began to hear God’s whispering call with greater clarity. The rest, as they say, is history.

The book, I think, came into my life at a moment when God knew I was ready for it. It just speaks to me. And I’ve been only too happy to listen.

Merton has fallen out of favor with some Catholics these days, who see him as a little too eager to do things like converse with Buddhists and study Zen. But the fact that his landmark memoir is included in the “25 Books Every Christian Should Read” gives me hope. He will endure. His voice will continue to be heard. He may even inspire more vocations like my own, stirring undiscovered yearnings and shocks of recognition among young men who encounter in Merton someone very much like themselves.

Thank you, Thomas Merton. Thank you, also, to the editors of “25 Books.”

And thank you, of course, Brother Jerome.