Lenten Campaign 2025

This content is free of charge, as are all our articles.

Support us with a donation that is tax-deductible and enable us to continue to reach millions of readers.

Mary Flannery O’Connor was an American writer steeped in the richness of Catholicism, with Southern Gothic sensibilities highlighting how epic human failings give way to a higher morality.

A devout Catholic, whose Irish émigré paternal great grandparents hailed from County Wexford, she gradually discovered that all God asked of her was to write. She was not meant to give great alms or pour herself into a cloistered supplication, that, like incense rising, brings the world closer to the Divine. No, she would warm the world with his love by painting with words, pioneering “Christian realism” — the divine infusing the human, the human taken up in the divine — on her way to winning Heaven at only age 39.

Born in Savannah, Georgia on March 25, 1925, the Feast of the Annunciation, Flannery was the only child of Edward Francis O’Connor, a real estate agent and World War I veteran, and Regina Lucille Cline. Her father’s grandparents had settled in Savannah shortly before the birth of their first child, on the Feast of the Assumption, 1868. Regina’s maternal grandparents, hailing from Tipperary, Ireland, had settled in Milledgeville, Georgia, on the eve of America’s descent into Civil War.

The small family lived on elegant Lafayette Square, directly across from the Cathedral of St. John the Baptist — the precursor church built by La Congrégation de Saint Jean-Baptiste, French émigrés seeking refuge from the Haitian revolution (1791-1804).

A desire to be left alone

Flannery, though gracefully attractive, never considered herself a beauty, her pigeon toes and weak chin engendering in her a desire to be left alone, or else! Perhaps given angelic hovering as a child, she had what she coined Freudian “anti-angel aggression,” as portrayed in a scene from Wildcat (2023), with fellow writer Robert “Cal” Lowell. Ah, but the angels were guiding her along fruitful paths.

When Flannery was 15, the family, suffering through her father’s final battle with systemic lupus erythematosus, moved to the “Cline mansion” in Milledgeville, just before his death on February 1, 1941.

After completing her postsecondary studies at a Georgia state college, she matriculated, in the fall of 1945, at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, two years later winning the Rinehart-Iowa award, based on her Wise Blood short story from The Geranium collection. That June she earned her Masters of Fine Arts and by summer 1948 was accepted at the Yaddo artists’ colony in Saratoga Springs, New York.

Moving to Manhattan, then Connecticut, the following spring, each day she attended early morning Mass followed by four hours of work on her novel. Christmas 1949, she fell ill with Dietl’s crisis, only to recover and continue writing. The following Christmas, however, while visiting Georgia, she fell ill again, spurring the family’s move to Andalucia Farm on the town’s outskirts.

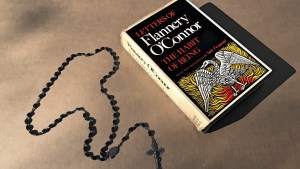

With the time she had left Georgia, she wrote a total of 600 letters to her mother along with Cal and other literary lights she befriended. Her collection of letters, The Habit of Being, published in 1979, reveal her to be a defender of the Faith.

She also sent continual letters to the heart to God, telling Him she wanted “to write a novel, a good novel,” and praying,

“Dear God, please, I can never seem to escape myself unless I’m writing. But strangely I’m never more myself than when I’m writing … Lord, please grant me grace. Let me be a typewriter. Please give me one good story.”

By 1952, she was formally diagnosed with the disease that took her father’s life.

Another novel and short stories

Her output until her death on August 3, 1964, in spite of, and/or because of, her illness, was prodigious, including completion of Wise Blood (1952), along with a second novel, The Violent Bear It Away (1960), and two collections of short stories, A Good Man Is Hard to Find (1955) and, the posthumously published, Everything That Rises Must Converge (1965).

While she was suffering and writing, she shared her feelings with Cal, at one point opining that this illness was better than a European vacation.

“It’s a lot harder to believe than not to believe,” she told a guest of Cal as dramatized in the film Wildcat (2023). “What people don’t understand is how much religion costs. They think that faith is a big electric blanket when, really, it’s the cross.”

One day, perhaps her cause of canonization will be formally submitted to the Vatican. For now, Flannery is a great literary saint who all writers can look to for strength and light.