Lenten Campaign 2025

This content is free of charge, as are all our articles.

Support us with a donation that is tax-deductible and enable us to continue to reach millions of readers.

For many, the terms “Hebrew Bible” and “Old Testament” seem interchangeable — simply two ways of referring to the same sacred texts. But while they largely contain the same books, they are not identical. The differences are not just in terminology but in order, interpretation, and even the format in which these texts were preserved and transmitted.

A matter of edition

At its core, the distinction between the Hebrew Bible and the Old Testament is one of edition. The Hebrew Bible — what Jewish tradition calls the Tanakh — is organized into three sections: the Torah (Law), the Nevi’im (Prophets), and the Ketuvim (Writings). Its final book is Chronicles(at least according to Talmudic tradition), which ends on a note of hope, looking toward the rebuilding of the Temple..

The Christian Old Testament, however, rearranges the books, closing instead with Malachi, a prophet who speaks of a coming messenger—a passage often understood by Christians as a foreshadowing of John the Baptist and Jesus. This restructuring alters the theological emphasis: while the Hebrew Bible’s arc is centered on the history and covenant of Israel, the Christian Old Testament is arranged to lead into the story of Christ.

Additionally, Catholic and Orthodox traditions include several books (such as Wisdom and Maccabees) that are not found in the Jewish canon. These books, known as the Deuterocanonical books, were part of the Greek Septuagint—the version of the Hebrew Scriptures widely used in Late Antiquity, even by Hellenized Jewish communities in the Levant and elsewhere. Protestant editions of the Old Testament, influenced by the Jewish canon, do not include these texts.

How editing changes meaning

Editing is never neutral. The way a story is told — where it begins, where it ends, and which details are emphasized — shapes how it is understood. For example, in the Hebrew Bible, 1 and 2 Samuel are part of the Prophets, framing Israel’s monarchy as a theological drama. In the Christian Old Testament, they are classified as historical books, shifting the emphasis toward a chronological account.

These editorial choices influence interpretation, and over centuries, they have shaped Jewish and Christian theological traditions in distinct ways. The texts are the same, but their arrangement guides the reader differently.

Scrolls vs. codices: A radical shift

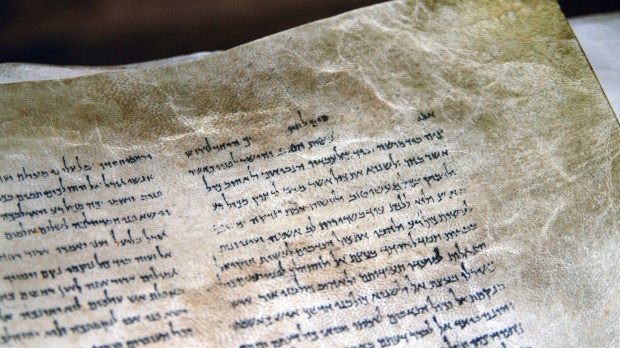

Beyond content, there is also a striking difference in format. The Hebrew Bible was traditionally written on scrolls, a format that encouraged reading one section at a time and reinforced the oral tradition’s importance. Scrolls were sacred objects, carefully preserved, and often stored in synagogues.

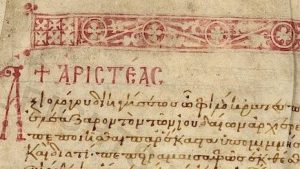

Early Christians, however, quickly adopted the codex — the ancestor of the modern book. A codex is bound, with pages that can be flipped, making it easier to reference different passages and compare texts side by side. This shift was more than practical; it symbolized a new way of engaging with scripture, one that emphasized study, cross-referencing, and missionary dissemination.

While Jewish tradition remained somehow attached to the scroll (at least for liturgical purposes, and particularly for the Torah) Christianity’s embrace of the codex helped shape the way the Bible was transmitted, studied, and interpreted in the centuries that followed.

The importance of understanding these differences

Recognizing these distinctions is not about division but about deeper understanding. The Hebrew Bible and the Old Testament share a foundation, yet their differences reveal how sacred texts are living traditions, shaped by history, interpretation, and even the way they are physically read. Whether on scrolls or in codices, these texts continue to speak across traditions, inviting readers to engage with them in all their richness.