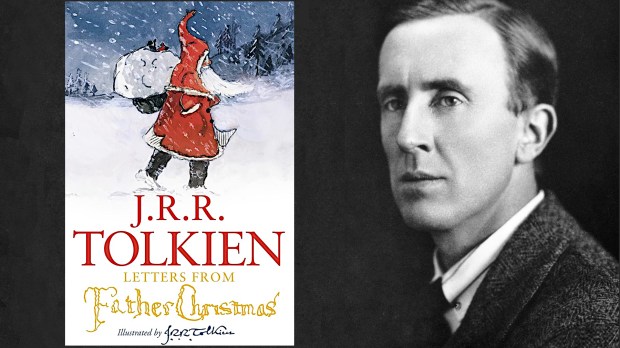

Long before J. R. R. Tolkien told stories about hobbits, elves and orcs in Middle-earth, he was telling stories about snow-elves, gnomes and goblins in the North Pole. He told these stories to his own children as he told stories about hobbits to his own children, long before they were told to the public after his books were published.

A lifelong practicing and devout Catholic, Tolkien and his wife Edith had four children: three sons and a daughter. In his role as paterfamilias, father of the family, Tolkien amused himself and his children every year with stories of the adventures of Father Christmas. As a talented artist and gifted storyteller, he wrote illustrated letters to his children which were purportedly sent to them personally from the North Pole every December by Father Christmas himself.

Father Christmas’s first letter

The first letter was written by Father Christmas in 1920 from his home address (Christmas House, North Pole), when Tolkien’s eldest son was three years old:

Dear John,

I heard you ask daddy what I was like and where I lived. I have drawn ME and My House for you. Take care of the picture. I am just off now for Oxford with my bundle of toys – some for you. Hope I will arrive in time: the snow is very thick at the NORTH POLE tonight.

Each subsequent Christmas, as John grew older and other children were born, the letters from Father Christmas became ever more elaborate and imaginative. New characters were introduced to the children as Father Christmas recounted his adventures.

There was the Polar Bear, Father Christmas’s helper who was, more often than not, more of a hindrance than a help; there was the Snow Man, Father Christmas’s gardener; Ilbereth the elf, his secretary, as well as snow-elves, gnomes and evil goblins.

News from the North Pole

Disaster struck in 1925 when the Polar Bear climbed to the top of the North Pole to retrieve Father Christmas’s hood. The North Pole broke in the middle and landed on the roof of Father Christmas’s house with catastrophic results. The hapless Polar Bear was also to blame the following year when he turned on the Northern Lights for two years in one go. As one can imagine, this shook all the stars out of place and caused the Man in the Moon to fall into Father Christmas’s back garden.

One letter arrived “by gnome-carrier” in an envelope with a hand-painted North Pole postage stamp. One letter had evidently been left personally by Father Christmas because he had left a muddy footprint on the carpet. In other years, it was delivered by the postman himself. Sometimes the letters were written in Father Christmas’s characteristic shaky handwriting; sometimes in the Polar Bear’s rune-like capitals; and sometimes in IIbereth’s gracefully flowing script.

Lessons from two fathers

Lettersfrom Father Christmas would be published in 1976, three years after Tolkien’s death and half a century after they were written. Their considerable charm is accentuated by the fact that they were composed solely by a father for his children and were never intended for publication. They also offer a cosey fireside foreshadowing of the familiar homeliness of hobbits and hobbit-holes.

As for the moral which we can glean from this charming friendship between Tolkien and Father Christmas, we can see it in the connection between fatherhood and Christmas. As a Catholic called to the married life, Tolkien was, first and foremost, the paterfamilias. His primary vocation, ahead of his calling as a scholar or as a storyteller, was to fatherhood. As a good husband to his wife and a good father to his children, he sought to emulate the life and love of the Holy Family in the life and love of his own family.

In this, as in so much else, the author of The Lord of the Rings is an inspiration to us all.