Old black and white photographs of Father Karol Wojtyła show him with his breviary while seated in a kayak, walking a country road with a backpack, or shaving in front of a tent in the woods. To university students who joined Fr. Wojtyła, these summer excursions not only represented an opportunity to spend several days in joyful rambles through the countryside, but also to draw from the spiritual and intellectual formation Wojtyła invariably built into their vacations.

Some of these students developed life-long friendships with Wojtyła. Even as Pope John Paul II, he remembered their names during audiences at the Vatican, acknowledged important anniversaries, and surprised them with personal Christmas cards. Even those who, like my father, were on the fringes of the core group known as “Swięta Lipka” (named after a village in Poland where they had originally met) still evoke Wojtyła’s profoundly formative influence.

An invitation to seek

When my dad met Karol Wojtyła, the latter had recently been appointed as auxiliary bishop of Cracow, the city where he had co-founded and performed with the Rhapsodic Theatre, written his early plays, and eventually discerned the call to the priesthood. A rising theatre director, my father admired Wojtyła’s spiritual and intellectual authority and felt an affinity with a man who shared his love of the stage.

Wojtyla took young peoples’ personal, academic, and professional interests seriously. And so, during the summer when my dad spent gleeful afternoons playing volleyball with the future Pope, he and the other participants were also charged with delivering formal talks on topics inspired by their fields of study. Gathered around a campfire or during an afternoon break, they listened to and debated each other’s ideas.

Generating such conversations defined Fr. Wojtyła’s educational methods. By inviting students to formulate their own questions and analyze them through focused discussions, he instilled the habit of seeking intellectually sound and morally consistent answers. He championed individual plans and goals yet broadened the young people’s aspirations by bringing them within the ambit of faith. He placed personal choices and achievements in light of moral responsibility and accountability to one’s conscience.

My dad, who indeed went on to build an illustrious career in theater and academia, to this day considers bishop Wojtyła’s influence as foundational for his professional life.

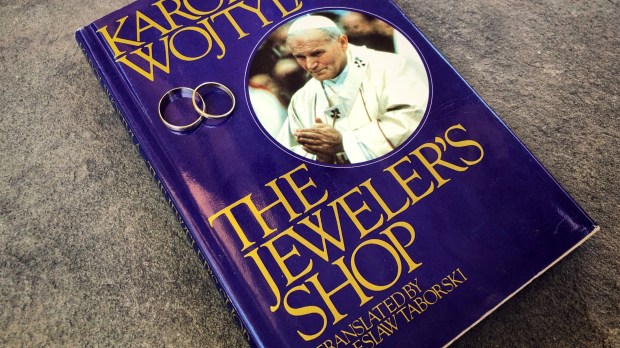

‘The Jeweler’s Shop’

Not surprisingly, The Jeweler’s Shop(1960) echoes the intellectual and pastoral insight that distinguished Wojtyła’s work as a teacher and mentor. The Pope’s most famous play, The Jeweler’s Shop focuses on love and marriage, arguably two of the most burning issues a person will face. Just as he did in direct conversations with students, Wojtyła explores these themes through the double lens of philosophy and pastoral awareness of the complexity of human circumstances. (Incidentally, he published his groundbreaking Love and Responsibility in the same year as this play.)

The play’s English translator, Bolesław Taborski, notes that Wojtyła’s dramas unfold largely through monologues delivered by people who appear together, yet seldom address each other directly. However, their speeches subtly comment on each other and thus advance the plot and clarify ideas. The Jeweler’s Shop adopts the same mode of expression.

Wojtyła writes in free verse. Harkening back to the performance style of the Rhapsodic Theatre, he highlights internal transformations of the characters, privileging the word itself as the vehicle of thought and emotion, uncluttered by fast-moving action, clever repartées, or scenery changes.

Three couples

Subtitled “A Meditation on the Sacrament of Marriage, Occasionally Passing into Drama,” the play follows the relationships of three couples. In Act I of The Jeweler’s Shop, Teresa and Andrew relate the story of their engagement. Although their brief and happy marriage ends with Andrew’s premature death, the couple’s love endures. The bridge of mutual commitment unites them beyond the grave, pointing to a supernatural dimension in which love finds ultimate and lasting fulfillment.

Act II introduces Anna and Stefan, who mourn their broken love, a marriage that never healed the distance created by hurt and disappointment. Anna in particular must choose whether to let her love die out or, like one of the wise virgins in the Gospel, await the bridegroom’s arrival.

In Act III, Christopher and Monica, adult children of the two couples we saw previously, walk their own path toward marriage. Christopher carries the ideal of his parents’ unwavering love; Monica struggles to overcome wounds inflicted by her parents’ rift. Throughout the play, two other figures connect the three couples. One is Adam, who serves as a father figure to Christopher, counsels Anna, and eventually attends the young people’s wedding. The other is the eponymous Jeweler, who not only measures the wedding rings made in his shop, but also seems to weigh each character’s soul as they come to buy or, in Anna’s case, to sell their wedding rings.

The ideal of love and the reality of life

If wedding rings symbolize marital unity and indissolubility, the cross supplies the other central image of the play. Bound by love, each couple also stands at an intersection of supernatural vocation and human limitations. Teresa grieves the loss of her husband whom she loves. Abandoned in her marriage, Anna cries out against the absence of love. Scarred by her parents’ unhappy relationship, Monica wavers between hesitation and trust as she becomes engaged to Christopher.

Each couple’s interaction brings to light tensions between two human temperaments, between their individual past and their joined future, between the desires of the heart and demands of reason, between each person’s own frailty and greatness. Too often, as the play suggests, a disproportion arises between the ideal of love and reality of life, where love and life meet, but also continually fall short of each other. The play resists happy endings. Questions remain, but so does the luminosity of truth which gently and mercifully suffuses human lives.

Revealing John Paul II’s pastoral genius

The play’s relevant themes and uncomplicated technical requirements have inspired countless productions by professional and amateur companies. The late Polish theater director Andrzej Maria Marczewski seems to hold the record, having personally directed The Jeweler’s Shop nine times in mainstream and regional venues. One of the most memorable of these performances took place on a floating dock, with the audience watching from the shores of a lake where Karol Wojtyła and his students had once spent summer vacation.

Marczewski attributed the enduring appeal of the play to the breadth of the human drama it portrays. Drawn with compassion and realism, the life of a single mother, a disillusioned couple, and their hopeful yet faltering children reflect situations as familiar today as they were in the Pope’s lifetime.

Growing out of Wojtyła’s actual encounters with young people, The Jeweler’s Shop bears witness to his pastoral genius, which combined unbending fidelity to revealed truth with caring attention to the most vulnerable and exalted areas of human existence. It is indeed a signpost for those who, like the play’s protagonists, seek to build a sensible structure out of the loves of their lives.