What was Judas’ sin and how is it relevant to us in the 21st century — especially in an election year?

There is a lot of speculation about Judas recently. College campuses are staging “The Last Days of Judas Iscariot,” a play that imagines Judas being put on trial, featuring witnesses including Sigmund Freud and Satan. And in the run up to the release of the 5th season of The Chosen, the filmmakers are revealing more about how Judas’ betrayal will be portrayed.

The Catechism mentions Judas three times, sharing important truths.

First, Judas’ sin reveals something of the violence of all sin, says the Catechism.

All sin is violent because it is from the devil. Satan, having rejected God, set his sights on undermining him — but he can do nothing against the all-powerful God. So the devil does violence to God’s creation instead. All sin shares the character of Satan’s sin — and Judas’ explicitly so.

Jesus says, in John 6, “one of you is a devil,” referring to Judas. In Luke and John, the devil enters Judas before he leaves Jesus’ company to betray him. But you can’t blame the devil exclusively. Judas is the betrayer.

The devil doesn’t cause us to sin; he plays upon a weakness that already exists. Just as angels fill us with courage and energy, the devil fills us with fear and dissipation. When we see the world through the devil’s perspective instead of God’s, it looks like a threatening place we have to conquer and control, instead of a blessed place with a creator who will take care of us if we allow him.

As Pope Francis put it: “The devil entered into Judas; it was the devil who brought him to this point. And how did his story end? The devil pays badly. He is not trustworthy. He promises everything, he shows you everything, and in the end he leaves you alone in your desperation to hang yourself.”

Second, we can’t know Judas’ (or anybody else’s) culpability in his sin, the Catechism says.

Even when it comes to the Passion, “the personal sin of the participants (Judas, the Sanhedrin, Pilate) is known to God alone,” says the Catechism.

Nonetheless, Judas is a cautionary tale as to how much our sin defines us. Whatever his level of fault, Judas is never mentioned in the Gospel without being identified as the one who betrayed Jesus. The same thing happens to us: Our evil choices, regardless of what rationalization we have, will be associated with us.

In Western history, this has often meant that Judas is portrayed as a caricature of evil, as a barely human monster. But even a nuanced writer such as Dante Alighieri depicts Judas as the epitome of sin: A man who would betray his divine friend, stuck forever in Satan’s devouring mouth.

Indications are that The Chosen will be easier on Judas,like Franco Zeffirelli’s film Jesus of Nazareth was. Luke Dimyan, who plays Judas in The Chosen, said, “I hope people realize that he’s not a villain but that he is a tragedy.”

While not exonerating the betrayer, he said, “He is a broken, sad story of failure … that failure is a reflection of what we can be … what any of us are capable of.”

He’s right. Any of us is capable of what Judas did — even at Communion, says the Catechism.

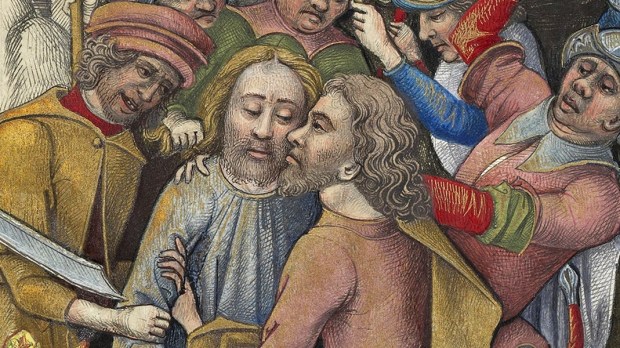

In telling us to approach the Blessed Sacrament with reverence and care, the Catechism quotes the Divine Liturgy of the Eastern Churches, in which communicants promise that the act will be reverent, and not like Judas’ kiss.

This is because of those two Gospel passages that associate Judas’ sin with the Eucharist. But there is one other passage that speaks of Judas’ motivation.

Judas objects in the Gospel of John when Mary, Lazarus’ sister, anoints his feet with costly perfume.

“Why was this ointment not sold for three hundred denarii and given to the poor?” he asks. John is quick to point out that he wanted the money not for the poor, but because he was stealing from the money box.

This is another typical human sin: To focus on the horizontal dimension of life, our concern for other creatures, instead of the vertical dimension — our devotion to God. No matter how noble it seems, to put love of neighbor over love of God is idolatry, as surely as worshiping any created thing is idolatry.

This is where Judas is relevant to politics.

In November, 2022, Pope Francis drew attention to the political aspect of Judas’ story, saying the betrayer “confuses Christ’s mission with political messianism.”

The idea is that Judas expected, like several other apostles, that Jesus had come to defeat the earthly powers of the enemies of Israel. He won’t. Politics is critically important. Evangelization is even more so.