“It truly seems that today’s science, suddenly going back millions of centuries, has succeeded in witnessing this primordial ‘Fiat lux,’ when a sea of light and radiation burst forth from nothingness with matter, as the particles of chemical elements split and assembled into millions of galaxies.” On November 22, 1951, before the members of the Pontifical Academy of Sciences, Pius XII proposed an analogy between the “Big Bang” — a hypothesis formulated a quarter century earlier in 1927 — and the original beginning described in the opening lines of Genesis.

Faith and science

His speech remains as memorable as it is controversial. Among his opponents, the famous astrophysicist Georges Lemaître, a priest, requested a private audience to correct the head of the Catholic Church. For the Jesuit scientist, there was no question of his Big Bang theory confirming the Bible, since theology and science represent two quite distinct fields, two parallel planes that don’t intersect and don’t have the same object.

Subsequently, Pius XII seems to have learned his lesson. A few months later, he addressed the participants in the World Astronomical Congress he hosted at the papal palace in Castel Gandolfo on September 7, 1952. His speech was no longer based on a “concordism,” according to which scientific truths were hidden in Scripture. Without expecting any eventual “scientific proof” of God’s existence, he panegyrizes the human spirit, which “has succeeded in taking hold of the immense universe, surpassing all the perspectives that the feeble power of the senses was, at first sight, able to promise.”

A promoter of both peace and science

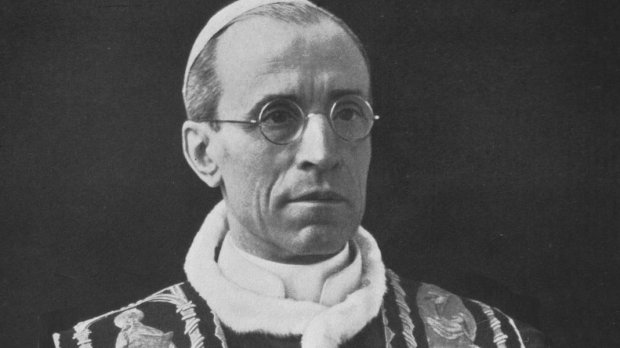

Pius XII was elected to the See of Peter (1939-1958) a few years after the transfer of the Vatican Astronomical Observatory from the Vatican Gardens to Castel Gandolfo (1935). Pope Pacelli left his mark on the Observatory at its then-new location in the Castelli Romani region south of Rome. A marble plaque salutes Pius XII as “an eminent promoter of both Peace and Science.”

The memorial recalls that in 1942, in the third year of his pontificate, he ordered that the “map of the sky” astrograph — with which the Vatican had participated in cataloging and mapping the positions of millions of stars, alongside observatories around the world — be transferred from the Vatican’s Leonine Tower to the Lazio hill, and that another tower, “as suitable as possible for astronomical observation,” be built there. The Latin inscription reads: “A work of peace while war raged throughout the world.”