Lenten Campaign 2025

This content is free of charge, as are all our articles.

Support us with a donation that is tax-deductible and enable us to continue to reach millions of readers.

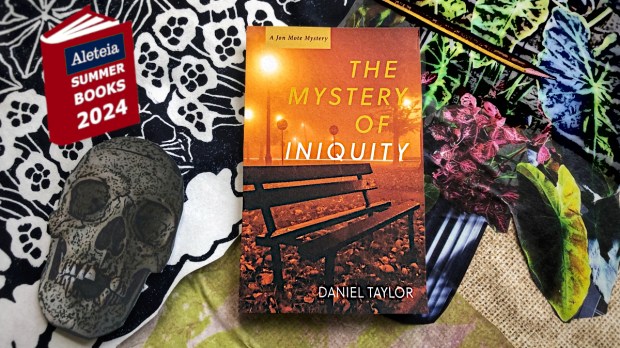

Editor’s note: The Jon Mote mystery series is one of many wonderful reads on Aleteia’s 2024 Summer Book List for Adults. We invited Dr. Justyna Braun, the Dean of Academics at the Chesterton Academy of Buffalo, New York to speak with the author of the Jon Mote series, Daniel Taylor.

A novel entitled Death Comes for the Deconstructionist will either intrigue or intimidate. Author Daniel Taylor quips that including deconstruction — the famously abstruse literary theory — in the title may have doomed sales of his book. Then maybe not. To me, a murder mystery woven out of themes in modern academia proved fascinating. Philosophy met life. And death. It challenged theology. It relentlessly asked how to live.

In the four volumes that make up this mystery series — Death Comes for the Deconstructionist, Do We Not Bleed?, Woe to the Scribes and Pharisees, and The Mystery of Iniquity — amateur detective Jon Mote brushes against unexplained deaths and terrorist organizations. In the first book, Mote investigates the death of a former university professor and intellectual superstar. Book two sees him accompanies a group of other mentally handicapped adults when one of them is accused of murder. Next, when hired to assist a Bible translation project, Mote finds himself following another trail of bodies as one Bible expert after another turns up dead. In the last book, friendship with a refugee family leads him into a dark world of hatred and revenge.

Seeking to expose culprits, exonerate the falsely accused, or safeguard the innocent, Mote embarks on a parallel examination of his own traumatic past, bound up with the life of his beloved mentally handicapped sister, Judy. In each of the novels, crime and suffering reveal a fundamental brokenness of the world, while attempts to solve them set in motion far-reaching inquiries: Is truth knowable? What does it mean to be normal? What is faith? Can forgiveness counter the force of evil? Hard questions, these, requiring patient probing. I asked Dan Taylor how his academic experience shaped the suspenseful and thought-provoking stories he tells.

Here is our conversation:

Aleteia:How did your academic expertise influence your choice of subject for the novels?

Daniel Taylor: I was prompted to write the first novel by decades of teaching and learning from novels, and the realization that, finding them so important in my own life, I ought—even in an ethical sense of “ought”—to try to write one. I have long been a great believer in the centrality of story in how we engage the world. I had told any number of autobiographical stories in my books; I thought I should try to tell an imagined one.

Initially, I didn’t know what I was going to “write about.” I began with a character. I knew he was troubled and trying desperately to make sense of the human condition generally and himself in particular. In short, he wanted to know what was true and good—and maybe beautiful—the old Greek triad. And how to shape a meaningful life around such things. But he was living at the beginning of the twenty-first century and none of those things was settled. In fact, all the traditional answers had long been under attack. So if I was going to engage “truth” and meaning in the year 2000 (the present time of the first novel), I had to deal with postmodernism. This applies even if one is not bookish or interested in ideas at all, because postmodernism (and now post-postmodernism) is the air we breathe.

I decided to make Jon Mote a failed academic/intellectual, maybe because it’s a world I’ve lived in. Literary theory and allusion found their way into the novels. The only way to deal with such without losing readers was to figure out ways to make tangled things more understandable—something I had being doing for many years as a teacher.

How do murder mysteries open up questions about existence and meaning?

I had no idea when writing the first novel that I was writing a mystery in the genre sense. I had, of course, produced a body and a sort of detective, so I guess I should have noticed. Still, my primary contention as a writer and as a reader is that I’m more interested in Mystery than in mystery, more interested in the Big Questions than in “who-dunnit?” I believe that is the starting point of every novel because at the center of the human experience is a rupture in shalom. Something is not as it should be. Characters are reacting to that rupture—some causing and compounding it, others trying to repair it. Out of that rupture and repair effort grow themes, worldviews, values, motivations, and other important things.

Your main character faces profound personal struggles and seems an unlikely candidate for a detective. Paradoxically, his disabled sister offers some of the sharpest insight in the novels. How did you create these characters?

I could say there is a link between Jon’s disability and his crime solving. Because he is so broken himself, he understands how brokenness works in life and is therefore suited to detecting its working out in crime. I thought the meaning of ‘mote’ as bit of dust floating in the air fits Jon’s image of himself as a failure and relates to his attempt to discover some significance to his life.

As for Judy, I consider her the moral center of the entire series and an unexpected source of wisdom. She is trying to keep Jon together — physically, psychologically, and spiritually — and he will not make it without her. She knows the t/Truth and it has set her free. And she wants Jon to know it too. My wife and I ran for three years a group home of eight mentally disabled adults when we were in our twenties. Judy was one of them, and I wanted to honor her and the other Specials by putting them in the novel and showing how successful their lives were despite their challenges. I learned myself in that time that I was not the teacher-protector but the one being taught, and the same proves true for Jon in the novels.

Writing from a Christian perspective, how do you maintain a coherent worldview without falling into didacticism?

It is a common fear among Christian writers to be thought a propagandist rather than a serious thinker or artist. When it comes to writing fiction, there are various strategies for avoiding that perception. One is to include believable characters who articulate opposing views. Another is to satirize both smug belief and smug disbelief. I believe that secularists are willing to consider truth claims accompanied by doses of humility and respect for other ways of seeing and believing. Having Jon Mote as an earnest but troubled seeker for a narrator helps dilute the impression that one is being manipulated. Ultimately, it’s a matter of craft. A good story dare not be mistaken for a sermon, a lecture, or a sales pitch.

Can readers expect to see another novel in the series?

Well, the ending of the fourth novel, The Mystery of Iniquity, makes it difficult to continue with another. But I have left chronological gaps between the novels and may try to wedge another in between the existing ones. I’d be sad to think I won’t meet up with Jon and Judy again on the page.