Lenten Campaign 2025

This content is free of charge, as are all our articles.

Support us with a donation that is tax-deductible and enable us to continue to reach millions of readers.

This year marks the sixtieth anniversary of the death of the controversial Catholic writer, Flannery O’Connor. Next year will mark the centenary of her birth. During her life, she suffered greatly from the debilitating effects of lupus, the disease which would eventually kill her at the age of only thirty-nine. In one sense, however, she is still very much alive, because she refuses to let the heathen culture rest in peace. Her ghost still haunts the wayward modern world that she had sought to shock into conversion.

Wildcat, the new film on O’Connor’s life and work, has sought to tame her. It seeks to do so by explaining her works in terms of psychosis and by explaining away her faith in terms of neurosis. The attempt fails. She remains untamed. The cat is still wild. No psychiatrist’s couch will contain her.

The irony, or the joke, is that Flannery O’Connor’s faith was always entirely rational. She saw faith and reason as being indissolubly married, as being one flesh. This was why she called herself the hillbilly Thomist. O’Connor was awash with the wisdom of Thomas Aquinas, and it was with the Angelic Doctor’s insight that she saw so incisively into the world’s psychosis and the neurotic nature of its narcissistic obsession with self-empowerment. She understood the anger and hatred beneath the surface of modernity’s angst and hubris. She knew why “the violent bear it away,” the title of her second novel, and why the heathen rage. In her work she shows them raging, often outrageously. She shocks us into seeing the shocking reality about ourselves.

“Why Do the Heathen Rage?”

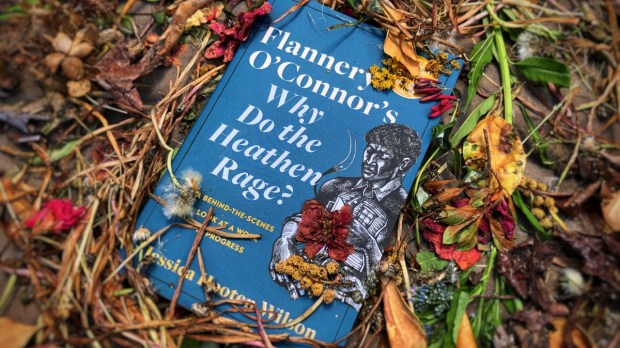

O’Connor’s incisive insight into the human psyche is found in the fragments of her unfinished novel, Why Do the Heathen Rage?, which is newly published by Brazos Press. Subtitled “a behind-the-scenes look at a work in progress”, the book interweaves the narrative fragments with penetrative commentary by the fine literary scholar, Jessica Hooten Wilson.

The Christ-haunted hallmarks of O’Connor’s narrative gifts are as present as ever in this unfinished literary gem. On the surface, there is the pride and superficiality of the flawed human characters; beneath the surface is the unheard truth and the unheeded presence of grace. The latter is evident symbolically in four giant oak trees, which had been named Matthew, Mark, Luke and John, by the previous owners of the farm on which the novel is set.

Blind to reality and faith

The new owner has no time for old trees or old truths, or anything rooted and resolute. “He would sense something larger than himself,” O’Connor writes, “and in his outrage, he would realize instantly that they were potential lumber, sufficient to panel an office or put up a Jiffy Home.”

The trees are spared the axe only because the farmer in his self-centered blindness had not noticed them. “[F]or all those years, he had appeared to notice those four oaks no more than he noticed the ground beneath his feet….”

The farmer’s son, as observed “in stunned disgust” by his mother, was typical of the faithless, faceless and graceless postmodern man, whom T. S. Eliot had satirized so scornfully in “The Waste Land” and “The Hollow Men.” “There was no innocence in him,” the mother laments, “no rectitude, no conviction of either sin or election. The man she saw courted good and evil impartially … Any evil could enter that vacuum. God knows, she thought and caught her breath, God knows what he might do!”

Evil and grace

The scene or the stage being set, the fragments of narrative which follow show the farmer’s son as a protagonist-antagonist. His contempt for others masks a contempt for himself. He hurts others and hurts himself in the process. He is not ignorant, but reads widely and well, including great Christian classics. His arrogance is worse than ignorance, however. It might be said that he cuts off what he knows to spite his faith. The twist is, however, in his untwisting. Ultimately, it is not evil that enters the vacuum of his emptiness but grace. “God knows what he might do,” his mother had thought. She thought more than she knew. It is God who knows what He might do, and it is God who does it!

This aspect of Flannery O’Connor’s work, present in the fragments of her final unfinished novel as it had been present in all her other work, was encapsulated succinctly by Jessica Hooten Wilson: “O’Connor had spent a career depicting … hounds of heaven that chase down and maul the unrepentant sinner.”

In truth, Flannery O’Connor did not merely depict hounds of heaven, she is herself a hound of heaven who chases down and mauls her unrepentant readers. Those who think she is only a wildcat should beware. She is likely to pluck out their eyes so that they are able to see.