“Then Simon Peter, who had a sword, drew it, struck the high priest’s slave, and cut off his right ear. The slave’s name was Malchus” (John 18:10). Thus reads the account of Jesus’ capture in the Garden of Olives.

In the cathedral in Poznan, a glass case hangs on the wall. Inside is a bladed weapon described on a separate brass plate as the “Sword of Saint Peter – the gift from Pope John XIII to Prince Mieszko I – in the 968 yr.”

Is this the same sword mentioned by St. John the Evangelist?

An ancient gift from a pope

In the display case under the sword there’s a copy of a page from the chronicle of medieval Polish historian Jan Długosz. Here is a translation:

The Pope then announced and appointed for the Church of Poznan a man of known virtue, faith and religiosity, an Italian named Jordan, of noble Roman lineage, from the family and house of Orsini. After his ordination and blessing received in Rome, he was ordered by the Pope in the year of our Lord 966 to go to the Kingdom of Poland to lead the Church there. The same Pope Stephen, in order to make Jordan’s beginnings more pleasant for the clergy and people of Poland, gave him the sword of St. Peter, with which the apostle, as they believe, cut off the ear of Malchus in the Garden of Olives, perhaps the same sword, or perhaps another one instead of that one, and blessed it in memory of such a splendid deed of the apostle; so that the Church in Poland would have a visible jewel to boast of (…). The same sword is also surrounded by fervent veneration today in the church in Poznań.

If you look at the website of the Poznan Cathedral, you will learn that the sword hanging on the wall of the temple is a copy made in 2005. However, the original, the sword that St. Peter the Apostle famously used, is actually in the treasury of the Archdiocesan Museum.

The treasure in the treasury

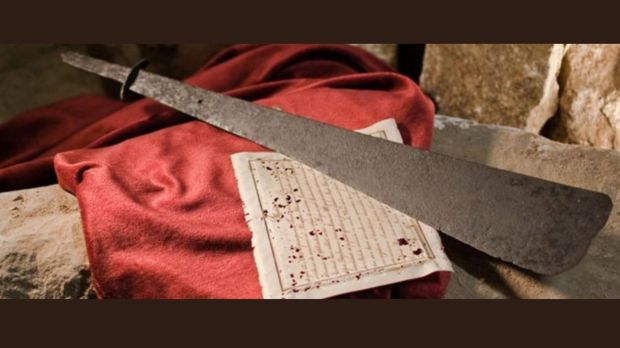

The iron sword — or to be more precise, the cleaver (for this is how this type of blade is formally classified, used mainly for cutting fish and other meat, less often for hand-to-hand combat) — is approximately 28 inches (70.5 cm) long and nearly 4 inches (9.4 cm) wide at its widest point. It widens towards the end of the blade. At one time it probably had a wooden handle, which has not survived to our time.

How is it possible that such a treasure — indeed, a relic — is so little known? The same question was asked by participants of a session devoted to an exhibit held in 2011 in Poznan.

The matter is complicated. The blade has a documented history of several centuries of veneration. For example, in several documents from the 17th and 18th centuries we read that such a relic was kept in the cathedral in Poznan and carried in processions and shown to the people to honor during important celebrations, such as the feast of St. Peter and St. Paul.

Gradually forgotten

However, at the end of the 18th century, Bishop Ignacy Krasicki — probably on a wave of Enlightenment skepticism — banned the sword from public display.

Over the years, it was displayed less and less often, and was somewhat forgotten. The extent to which it was forgotten is evidenced by a photo taken in the cathedral’s sacristy in 1945. It shows the effects of the robbery carried out by the Nazi German forces: emptied and scattered boxes, crates, and tubes from which the occupiers removed various valuable items. Above this disorderly pile quietly hangs on the wall in a display case the sword of St. Peter, which apparently did not arouse the interest of the looters.

Renewed interest

It was not until the mid-1980s that the sword was moved to the museum by its then director, Rev. Canon Stefan Tomaszkiewicz. On his initiative, the object underwent protective conservation treatments.

“It would be good for [the blade] to become an icon of the city,” Aleksandra Pudelska said during the 2011 conference. She noted that it’s the first treasure of Christian Poland and a witness to the nascent Polish state.

“The people of Poznan can be proud of owning this treasure, and every Pole should know about it,” the museum’s website said.

Different opinions

It should be noted, however, that not all historians are convinced of the relic’s authenticity. Admittedly, research done by scientists at the Polish Army Museum in Warsaw on the shape and type of alloy used to make it indicates that the cleaver was forged in the first century AD on the eastern borders of the Roman Empire. However, representatives of the Greater Poland Military Museum are more cautious in assessing the age of the weapon and are more inclined to assume that it is a medieval copy.

Even if St. Peter’s sword might not date back to the first century, but to the 10th or 14th century, it is an edged weapon that, next to the coronation sword of the Polish kings (kept at Wawel), has the longest documented history in the country. So it’s hard not to agree with the author of the post on the museum’s website that the historical artifact deserves much more attention than that which it currently attracts.

Sources: “Miecz św. Piotra z katedry poznańskiej. Losy zabytku” in “Ecclesia. Studia z Dziejów Wielkopolski,” vol. 6, 2011; Archdiocesan Museum in Poznań; Wikipedia.