Adapting great books to the big screen is a notoriously ill-fated task. And Flannery O’Connor — a pivotal player of Catholic history and master of Southern Gothic storytelling — is among the greatest of our modern writers. Only a few filmmakers have been daring enough to try to bring her work to cinemas, the most prominent being John Huston with his 1979 adaptation of O’Connor’s first novel, Wise Blood.

Ethan Hawke and his daughter Maya have risen to the challenge anew, dramatizing several of O’Connor’s stories in their new film Wildcat. But the Hawkes take on an added challenge: weaving the stories in and out of the very first Flannery biopic. This utterly captivating film explores the strained relationships, physical suffering, and above all, spiritual longing that made this young woman the force of nature that she was.

The Hawkes have their own artistic perspective on all this, and such an ambitious undertaking isn’t without the occasional misfire, but the overall result is brilliant as a peacock’s tail — the best of all possible Flannery biopics and a decisive victory for the intersection of art and faith.

For those new to O’Connor (played by Maya Hawke), the film’s epigraph from one of her essays — which, like her letters, are helpful to read together with her stories — says it all: “I’m always irritated by people who imply that writing fiction is an escape from reality. It is a plunge into reality” — and, she goes on to add, “it’s very shocking to the system.”

O’Connor’s writing is all about these shocking plunges — both for her characters and her readers. One typically finds the same set of words trotted out wherever O’Connor’s stories are discussed: grotesque and gothic, dark and disorienting, violent and comic — in a word, unsettling. “To the hard of hearing you shout,” she wrote, “and for the almost-blind you draw large and startling figures.”

For almost a century, O’Connor’s strange stories of misfit fundamentalists, atheists, prophets, and criminals — two novels and 31 short works in total — have fascinated readers, and their influence is felt all over popular culture, from the music of Bruce Springsteen to the films of the Coen Brothers. But they’ve also left many others — especially religious readers expecting a conventional spiritual uplift from a devout Catholic writer — feeling bewildered and scandalized.

Leaning in

Rather than shy away from this modus operandi, the Hawkes lean into it. Wildcat is— from the opening frames riffing on “The Comforts of Home” — a Flannery-esque presentation of both O’Connor and her stories. Its dark and disorienting quality will pose a challenge to those unfamiliar with O’Connor, but also keep her fans on their toes: an early scene inspired by “A Good Man Is Hard to Find,” for example, doesn’t quite line up with the story — and in fact, draws on dialogue from The Violent Bear It Away (“The world was made for the dead. Think of all the dead there are . . .”). The Misfit’s pointed gun — spliced with O’Connor’s clacking typewriter — draws fans back into the shock of what they’ve become accustomed to seeing.

But such deviations are rare, and the Hawkes have clearly done their homework. Fans will delight in the many lines from O’Connor’s essays and letters strewn throughout the dialogue. (Even her famous appearance in a Pathé newsreel as a young girl in Savannah comes up.) And the stories themselves — including classics like “Parker’s Back” and “Good Country People” — are executed with deft and dutiful strokes, each one like a wave rising and falling and shaking us around in turn.

One of the key motifs emerging throughout the film, especially in “Revelation” and “Everything That Rises Must Converge,” is that of race. On this matter, too, Hawke has done his homework, and Wildcat thankfully cleaves to the “knotty but extremely important” witness of O’Connor, who understood racism from the inside out and remains a powerful weapon for combatting it. One particularly jarring but instructive moment in “Revelation” is Ruby Turpin’s imagined conversation with a domesticated, soft-focus Jesus, who parrots her own racist and classist garbage back to her. But Hawke, like O’Connor herself, means to show us that Turpin — like so many to this day — has fashioned Jesus in her own image and likeness; it’s only in the titular “revelation” turning her world upside down that Christ’s grace truly seizes her.

We enter and exit all these stories via O’Connor’s own mind and typewriter, and when we first meet the fledgling writer, she is pitching her first novel, Wise Blood, in New York. After discussing the fallout with her friend, the poet Robert Lowell (“Cal”), she journeys back to Georgia to her mother, Regina (played by Laura Linney). O’Connor’s romantic tension with Lowell (which was only obliquely hinted at in letters) and personal tension with her mother (Linney also plays all the grating mother figures of the stories, and Maya plays the mother’s child, challenger, or both) may be artificially dialed up for effect, but the point is clear, and noble: O’Connor’s art did not emerge in a vacuum, but out of her ordinary dealings with fallen people in a broken world, where she found herself something of a misfit everywhere she turned.

Grief … and wonder

It emerged, too, out of her own acquaintance with grief. After her journey back home to Georgia, she finds out she has lupus — the same disease that overtook her father, and would eventually overtake her at just 39 — and back home in Georgia is where she will stay. We watch O’Connor collapse in a weakness compounded by agony: “The reality of death has come upon me and a consciousness of the power of God has broken my complacency like a bullet in the side. A sense of the dramatic, of the tragic, of the infinite, has descended, filling me with grief, but even more than grief, wonder.”

But far from being dissuaded from writing, she allows it to shape her life as a writer that much more, persevering on crutches to and from her typewriter, where she presents readers with the lame, the blind, the deformed, and other “temples of the Holy Ghost.”

“A sense of loss is natural to us,” she would later write. “The freak in modern fiction is usually disturbing to us because he keeps us from forgetting that we share his state.”

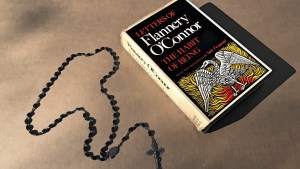

But the most prominent aspect of O’Connor’s life in Wildcat is her Christianity. The Hawkes do not tuck away O’Connor’s faith; on the contrary, they give it its proper place — which is to say, center stage. From the very beginning of the film, signs of O’Connor’s Catholicism — rosary beads, statues of Mary, churches, the sign of the cross, and references to luminaries like Thomas Merton and Thomas Aquinas — are everywhere.

But these are all tangible signs of an intangible relationship: throughout the entire film, we are drawn into O’Connor’s inner monologue of prayer, drawn from the posthumous Prayer Journal of her younger years. The focus of her prayer is consistently on honoring and channeling God with her writing, on finding herself yet getting herself out of the way — an ongoing spiritual struggle deeper and far more agonizing than any physical struggle. “Creativity,” she prays at one point, “is you inside us rising. Writing is dead without you. Oh Lord, please rise in me. Make this dead desire living.” And far from a private preoccupation, her life of prayer spills outward: we see O’Connor’s famous challenge to a symbolic view of the Eucharist at a fancy dinner party (“If it’s a symbol, then to hell with it”), and a powerful heart-to-heart with a priest (played by Liam Neeson) rich with insights about prayer, authenticity, faith, service, and the tensions of the Catholic soul.

O’Connor famously called herself a “hillbilly Thomist,” and once said about the Eucharist: “It is the center of existence to me; all the rest of life is expendable.” The Hawkes have admirably taken her at her word, even if they don’t totally see eye to eye with her: the Catholic faith was the key to understanding Flannery O’Connor. It was also the key to understanding her art. As she herself attested time and again, her writing wasn’t bleak or nihilistic; on the contrary, it was almost always about a “moment of grace” breaking into the world — a grace that was “usually rejected.”

In drawing together O’Connor’s concrete struggles and visionary prose, Wildcat is an important monument to what Pope St. John Paul II called “the special vocation of the artist,” especially the vocation of the writer, and a fitting tribute to one of the greatest and most valiant to ever live it.