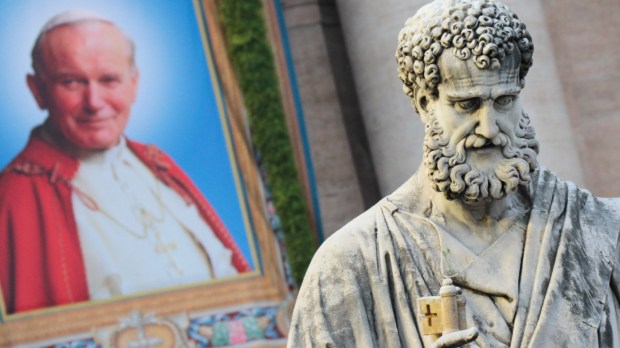

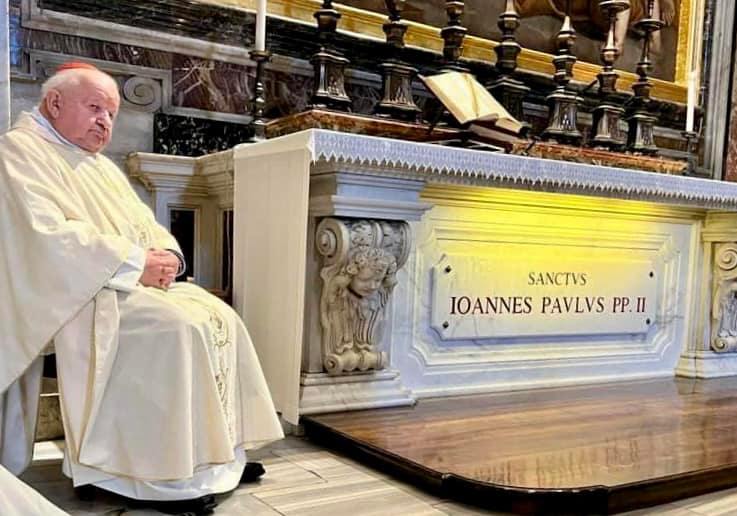

Their numbers vary from a few dozen to a few hundred depending on the week, but the rite is immutable. Every Thursday morning at precisely 7:10 a.m. — so that it can be broadcast on Vatican Radio — the Poles at the Vatican and those on pilgrimage to Rome gather for a Mass at the tomb of John Paul II, “their” pope, the man who restored dignity to a people crushed by the Communist yoke.

“I remember very well the reaction of the people in Poland, in the streets, when they learned of the election of the archbishop of Krakow on October 16, 1978,” recalls a Pole now living in France. “The regime-controlled media reported it quite briefly, and there was no great mass demonstration of joy, but in the way people stood, walking down the street, there was an energy, a new-found pride. They stood up straight. John Paul II had restored hope to an entire people. That moment is unforgettable,” he says.

A constant flow of pilgrims

To situate the legacy of John Paul II in Rome, one must first recognize the red and white flags of the many Polish groups, visible every day and at every Angelus and general audience. For millions of Poles of all generations, the pilgrimage to Rome is an unmissable experience. Even people of modest means save up for several years to make this journey in the footsteps of their pope, who reigned for over a quarter of a century.

The Thursday morning Mass at John Paul II’s tomb is often celebrated by Cardinal Konrad Krajewski, currently Prefect of the Dicastery for the Service of Charity. He served the Polish Pontiff very closely as papal master of ceremonies during the last years of his life, when his illness required great care and ingenuity in getting him into his liturgical vestments and physically supporting him at celebrations. Krajewski’s attentive, concerned gaze is still visible in many photos from that period.

Popularity beyond his compatriots

But this affection extends beyond the confines of Polish nationals alone, and sometimes reveals itself in more unexpected profiles, such as the young priest from Benin who I met at Thursday morning Mass. Without ever having set foot in Poland, he took it upon himself to learn the Polish language out of a passion for this mystical and intellectual pope, whose thoughts he wanted to grasp in their original text.

For pilgrims from Italy, France, and the USA, the tomb of John Paul II is also a must-see on any visit to the Vatican. It’s not uncommon to hear children born well after 2005, and therefore having never known him, ask their parents about this figure whose importance they perceive by noticing the number of people praying in front of his tomb.

A pope who remained popular with the Romans

Around the Vatican and in the city of Rome, the face of John Paul II still appears in many souvenir stores, religious communities, and parishes. For instance, Fr. Stefano Cascio is the dynamic parish priest of St. Bonaventure parish in a difficult district on the periphery of the Italian capital. He proudly displays photos of John Paul II blessing the church under construction in the late 1970s, when the Communist municipality of Rome was threatening to prevent its construction: a story that echoed the pope’s own struggles as archbishop of Krakow.

“As long as his health allowed, he was very attached to his role as Bishop of Rome, visiting almost every parish in his diocese,” recalls Fr. Stefano, who admires his physical and spiritual courage. He entered the seminary under John Paul II’s pontificate, before being ordained a priest by Benedict XVI in 2008.

For some Romans who are more detached from the Church, however, the succession of three non-Italian popes remains a difficult reality to assimilate. This was demonstrated by a scene recently observed in a restaurant near the Vatican. Pointing to the paintings of contemporary popes on the restaurant’s walls, an elegant woman said, “Quello è il Polacco, e quello il Tedesco” — “That one’s the Pole, and that one’s the German.”

This way of referring to John Paul II and Benedict XVI by their nationality is relatively common in Rome, and shows how difficult it is for the inhabitants of the Eternal City to “adopt” a pope from elsewhere, even though this reality has been part of the life of the local Church for over 45 years.

Pope Francis: rupture or continuity?

Coming from Argentina, with a way of expressing himself that is naturally different than his predecessors, Pope Francis sometimes shocked Polish visitors by giving the impression of being annoyed by a form of “cult of personality” around John Paul II. His short homily at the canonization in April 2014 disappointed many pilgrims. On a more academic and intellectual note, the change of leadership at the head of the John Paul II Institute for the Family, which took place during the summer of 2019, appeared to some as a way of liquidating the Polish pontiff’s legacy.

This interpretation is rejected by the current president of this institution, now renamed the “Pontifical John Paul II Institute for Studies of Marriage and Family.” Interviewed by I.MEDIA in 2023, Monsignor Philippe Bordeyne explained that “what we use today to think about marriage and the family is both a personal and conjugal ethic, and a social ethic. This is what doctrine is about. But it goes hand in hand with a detailed understanding of today’s difficulties and opportunities. This work corresponds to Pope Francis’ wish for the John Paul II Institute. I try to take into consideration the extent of current changes, and to draw resources from doctrinal tradition, but also from philosophy and the human sciences, to show that the relevance of the Gospel remains astonishing today.”

From this point of view, it would be a disservice to John Paul II’s personalist philosophy to see it as permanently fixed thought, without updating its intellectual heritage to take account of today’s challenges.

“Rehabilitation” of John Paul II?

This debate on the Polish Pontiff’s legacy will be revisited in April 2025, on the 20th anniversary of John Paul II’s death. In the context of the Jubilee, this commemoration will certainly provide an opportunity for his most senior collaborators and the reigning pope to pay him a heartfelt tribute, after numerous media attacks on his handling of abuse cases, which have weakened the perception of his pontificate, with some even calling his canonization into question.

Is it time for a sort of rehabilitation of John Paul II? The recent document Dignitas infinita quotes him 12 times. And at last Wednesday’s general audience, in his words to Polish pilgrims, Francis saluted the memory of the man who made him a cardinal in 2001.

“Looking at his life, we can see what man can achieve by accepting and developing in himself the gifts of God: faith, hope and charity,” the Pontiff said, asking everyone to remain “faithful to his legacy” and therefore to “promote life and not allow ourselves to be deceived by the culture of death.”

The promotion of the “civilization of love” against all forms of polarization and egoism thus remains a topical and living legacy of the Polish pontiff.