This past Lent, I gave a few spiritual retreats based on the poetry of T.S. Eliot. I’ve always been a big fan of his because he was born in my hometown of St. Louis, living here until he left for Harvard just after the turn of the early 20th century. A few months ago, as I was preparing for the lectures, I went by his old house just to look at it and get a sense for the place where he grew up. It’s a beautiful old Victorian home that appears to still be occupied.

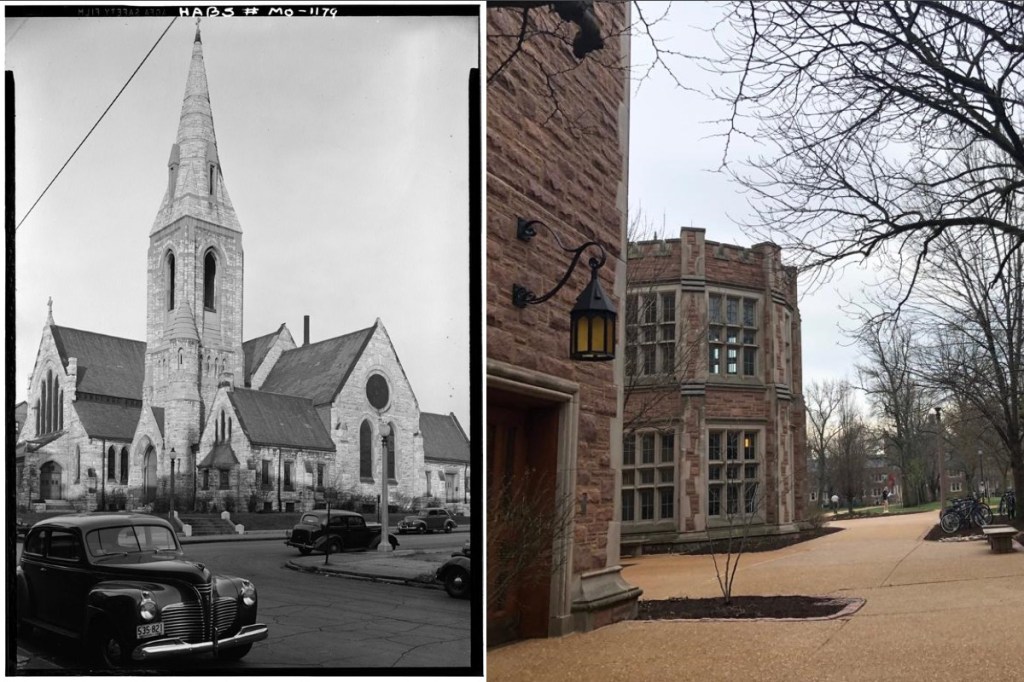

Later that day, I researched the estimated value of the house because I had the temporary fever dream that I could purchase it and live in the T.S. Eliot house. The house is “slightly” out of my price range. Like, hundreds and hundreds of thousands of dollars out of range. So now the dream is over. The Eliot family, suffice it to say, were well off. In fact, they were major movers and shakers in 19th-century St. Louis. William Greenleaf Eliot, the poet’s grandfather, was the minister of a well-to-do Unitarian church here in town. He founded a prep school for girls that is still in operation, as well as a college that has grown into a major, well-respected university.

The move to England and toward God

T.S. Eliot eventually ended up in London, where he established a literary magazine and worked with a local publisher. It was here, in 1922, that he published “The Waste Land” and became famous. I’m not entirely convinced by this, but some literary critics think that the rhythms of St. Louis ragtime (think Scott Joplin, who lived and worked in St. Louis for a few years right around when Eliot would have been a teenager), can be found in “The Waste Land.”

In any case, the poem certainly has its own particular modernist form. It’s a fragmented piece of writing meant to reflect a fragmented era. It was Eliot’s cry for help. He felt like, in the midst of modern life, he had become lost.

Several years later, he began to put the pieces back together. In a move that shocked the literary world, he became a Christian. Many of his friends thought he’d made an impulsive decision that he would quickly regret. Soon enough, they thought, he would forget all about spiritual faith and regain his senses. He never did. Eliot lived the rest of his life as a sincere believer.

Searching for meaning amidst the horrors of war

During the Second World War, he remained in England and was subjected to the danger of German air raids. Once again, the world seemed to be going to pieces. This time, however, because of his religious faith Eliot had a source of strength and didn’t fall back into the melancholy of “The Waste Land.”

Instead, Eliot wrote the “Four Quartets,” four poems in which he meditates on time and timelessness, memory and hope, nostalgia and exploration. He doesn’t sugarcoat the horrors of modern warfare or pretend that having become a Christian had erased all his problems, but neither does he throw his hands up in despair. Instead, he searches out the deeper meaning of our existence in the midst of chaos.

Water and life

One of the four poems, “The Dry Salvages,” begins with a memory of the Mississippi River which as a young boy he would have observed flowing past St. Louis; “I think that the river/ Is a strong brown god — sullen, untamed and intractable.” The poem goes on to make an extended meditation on the miracle of water, the way it carves through landscapes, creates and destroys, gives life and drowns. Water becomes a metaphor: “The river is within us, the sea is all about us.”

Eliot is asking, essentially, will we be able to bear up under the weight of eternity that is placed in our hearts? Or will we give up? Perhaps he’s thinking of his own baptism and how the water that was poured over his head saved him from despair. He submitted to a symbolic drowning, a death in water, and the result was rising to new spiritual life.

Getting our attention

The job of a poet is to get our attention. Eliot has a unique way of saying things that, when we read them, are obviously true but that we never would have been able to formulate for ourselves. His words are simple but loaded with depths of meaning. By pointing out the importance of water, a fact we all know but take for granted, he’s trying to get us to pause for a moment take stock of our own spiritual condition.

The Dry Salvages are a series of rocks in the ocean off Cape Ann, Massachusetts. The sea is beautiful to behold in the daylight, but dangerous to sail at night. You never know what rocks are lurking in the waves to capsize your boat. This is what buoys are for. They wobble on the waves and their bells clang — a warning to sailors — danger lurks here. As Eliot puts it, the buoys, “Clamour of the bell of the last annunciation.”

A “calamitous” Annunciation

That word, annunciation, is one that no poet can use without his readers immediately thinking of the Blessed Virgin Mary and the Angel Gabriel. Each year on March 25 (this year it’s moved to April 8 because of Holy Week), we celebrate the meeting of Mary and Gabriel in which Mary learns that she is to give birth to Christ. The Annunciation upends the course of her life. It changes everything. The writer Thomas Howard, commenting on the “Quartets,” calls the Annunciation “calamitous,” because it, “upset every single one of her expectations as to how her life on this earth was to play itself out.”

Then Howard makes a point that has stuck with me ever since I first read it. He says, “Eliot’s poem is itself just such an annunciation.” Like the voice of an angel, it summons us to consider the direction of our lives. Like a bell clanging loudly, it rings and rings and rings again, warning us to sail with care.

We are the recipients of ceaseless annunciation, not only through a single poem but every time we pause and attend to the beauty of the world around us, the presence of eternity saturating time and space like an ocean of water. God is constantly announcing himself to us and directing us towards our proper end. He has purposes in us and is ever calling us onwards.

Every day, I listen for the clanging of the bell. These are deep waters, and I don’t want to carelessly wander. If anything, Eliot’s poem is a call to action: don’t let precious time slip through your fingers. Redeem the time. Search out the Lord of time. As Eliot would have it, “Not fare well,/ But fare forward, voyagers.”