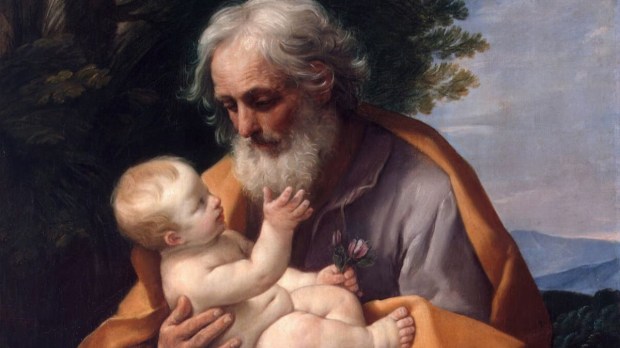

Guido Reni’s St. Joseph Cradling the Infant Christ is one of my favorite depictions of Joseph in the sacred art tradition. As Elizabeth Lev points out in her book The Silent Knight, St. Joseph has gone through numerous artistic changes over the decades. This is why, in your parish, you might have a statue of him as a young strong carpenter or, equally likely, as an older bearded man. Sometimes he’s a distant patriarch, other times he’s a tender father. Joseph is a man of few words and, after the infancy narrative in the Gospels, he no longer appears in an active role, so artists have had freedom to interpret his character.

Reni was an Italian who painted during the counter-reformation of the 17th century in the Baroque style. The Protestants had been attacking the Church as too academic and theoretical. Luther, for instance, made a bonfire in which he burned every book of canon law he could find. His only regret was that he didn’t have any copies of Thomas Aquinas’s books to burn. In response, Catholic religious artists re-emphasized the humanity and closeness of the saints.

Earthy and relatable

A true master of this style of painting, Reni gave us saints who are earthy and relatable even while their souls are visibly luminous with God’s love. In his St. Joseph painting, you won’t see a halo or carefully posed choirs of angels. There’s a highly symbolic and deep meaning to the more formal, traditional iconography of the Church, but Reni is doing something different.

Both forms of artistic expression are beautiful. Both are necessary. One illuminates the heavenly aspect of our faith and functions as a window into Heaven, the other reveals the human perspective and how we are drawn into another life through grace. The one views earth from Heaven. The other views Heaven from earth.

When I contemplate Reni’s picture, here is what I see…

A man lost in wonder

Our eyes fix first on the countenance of St. Joseph. Reni has painted his expression with masterful sensitivity. His gaze is at once tender and protective. He seems lost in wonder, perhaps asking himself how he has become the father of this perfect child, this infant whose arrival was portended by dreams and controversy and angelic intervention.

As a father myself, I know how long the preparatory period is when a new baby is on the way. Nine months unfold into excruciating eons. For me it was always a period of excitement mingled with anxiety. I was excited to finally meet our new little one but also anxious about everything that could go wrong. A father naturally feels protective.

We do our best. Preparations are made, but when the baby finally arrived, I realized none of it was enough. There was no way I ever could have adequately prepared for that child. No plan would have encompassed the reality of what it’s like to hold a baby in your arms as a new father. There’s no way I can love them the way they deserve, protect them from the wounds of living in this world, map out every contingency.

Joseph the protector

In the end, all a father can do is give his child his very best and then commend them to God’s perfect love. Where I fall short, I have faith that God the Father provides.

This is precisely the scenario of St. Joseph in Reni’s painting. You’ll notice the small figures in the background. These are Mary and the Angel Gabriel, who has sent them on a flight to Egypt to escape danger. This is why Joseph seems so protective. The world is out to destroy his child, and he will do all in power to keep him safe.

In the end, though, it’s in God’s hands.

Hands that speak to us

After the expression on his face, the second thing I notice is St. Joseph’s hands. His weathered hands are contrasted against the pure skin of the infant. Joseph’s hands are paternal. He has lived a full life and seen the best and worst it has to offer. These are hands worn with the hammering of ten thousand nails, the sanding of wood grain until it reached perfection. The hands are those of a builder, a maker. They are the symbol that encapsulate the beauty of the ancient world.

This is why, by tradition, St. Joseph was older when he became betrothed to Mary. He is of a priestly family and forms a link with the Old Covenant, representing the promises of God from antiquity to bless his people. The Old Covenant was an agreement born of grace. God loved his people so much that he promised himself to them in the manner a husband promises himself to his wife.

These same priestly hands hold the Christ child, who is the incarnation of the new covenant. In the hands of St. Joseph, the beauty of the old law is fully unveiled, written into the care with which they hold the Son of God.

The hand of baby Jesus

From the hands of St. Joseph, my eye drifts to the exploratory hand of Christ, reaching out to perhaps tug his Joseph’s ear, feel his beard, or fishhook him by the mouth. Children learn through their senses, including the sense of touch. They’re testing out their growing bodies, connecting neurons in their brains for dexterity, and feeling out their ever-increasing strength.

Essentially, babies integrate into the space into which they’ve become empathetic participants. They’re both part of the space and also learning to manipulate it. The space is tactile and embodied, so they pick up objects, bang them, pull at them, and try to move them.

A baby might weigh out a plastic baby toy like a bar of gold, holding it to the sunlight in the window like a jewel in a shop display. The infant, like an awed window-shopper, stops and stares, wondering why no one else has noticed what they’ve noticed, that these objects of color and form emerge like a miracle from the background. Other things are different from me. They have their own existence and integrity. No matter that it’s a cheap plastic toy, if I just reach out and touch it, I’ll know that it’s a treasure.

The Christ Child reaches out to St. Joseph as if to grasp a treasure. The father, for now, holds the child. But soon enough, the child will grow strong and hold his father. In fact, through his perfect sacrifice at the Cross he will hold the entire world, pouring out his life for the sake of saving his treasure.