Lenten Campaign 2025

This content is free of charge, as are all our articles.

Support us with a donation that is tax-deductible and enable us to continue to reach millions of readers.

The main source of persecution of the Church has changed over recent decades, but the response of Christians under pressure has remained constant, says the new executive president of the international Catholic charity Aid to the Church in Need.

Regina Lynch became one of the first women to head a pontifical foundation when she was appointed executive president last June. She now oversees the work of ACN International and its network of 23 national offices.

She began work with the foundation when its founder, Fr. Werenfried van Straaten, was still alive. His vision was to assist displaced Catholics in the wake of the Second World War, when widespread destruction included the loss of churches in Western Europe.

But the organization soon was called to respond to a new challenge.

An eye-opener for an Irish youth

When in September 1980 Lynch began a job as a secretary in the headquarters of ACN, in Königstein im Taunus, Germany, “it was the beginning of the end of Communism.”

“The first witnesses started coming” to the West, she said in an interview with Aleteia – “bishops, priests who had been in the gulags, who had been imprisoned in solitary confinement for working in the underground. It was a real eye-opener for me.”

ACN responded by trying to support the persecuted Church behind the Iron Curtain.

Lynch admitted that although she had been a practicing Catholic in her native Northern Ireland, where her family “lived between the priest’s house and the church,” her faith life did not go much beyond Sunday Mass.

“I wasn’t really aware that there were in the modern day people ready to die and to suffer imprisonment for their faith,” she recalled.

“I wasn’t really aware that there were in the modern day people ready to die and to suffer imprisonment for their faith,” she recalled.

She felt a longing to go back home, but every time she was about to resign, ACN offered her a higher position. She was put in charge of projects for Africa, and her first trip to the continent consisted of stops in Guinea, Benin, and Ghana.

“At that time, there was a whole wave of Marxism in Africa in the 1980s,” she said. “We spent a week touring through Guinea-Conakry, and that was the time when the now Cardinal [Robert] Sarah [retired Prefect of the Congregation for Divine Worship] was the young Archbishop of Conakry. All the missionaries had been expelled, and they were left with a handful of local priests and sisters. Ahmed Sékou Touré was the Marxist dictator,” and he had put Archbishop Raymond-Marie Tchidimbo in prison.

Sarah was appointed to succeed him at age 34, and in Sékou Touré’s Marxist dictatorship had put a price on his head, Lynch said.

“We just spent a week with him, and I listened to him talking about the many challenges for him as a young archbishop but also leading a flock through a time of persecution when it could have ended up with his death,” she recalled.

New challenge

Fast forward to the 2010s and 2020s, and Marxism largely has been replaced by another threat in the danger Christians face.

“I think a great area of concern for us today is the growth of a form of Islam which is very radical, where you have jihadists,” said Lynch, 66, who as ACN’s project director from 2008 to 2023, was responsible for 6,000 projects in more than 140 countries.

She cited a number of specific examples of radical Islam’s challenge for the Church: the great decrease in the number of Christians in the Middle East, or believers being treated like outcasts in places like Pakistan, where many are wrongfully accused of blasphemy and where girls are prey to being kidnapped to marry older Muslim men.

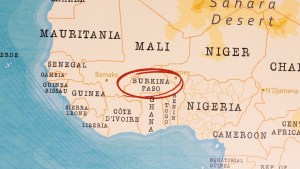

“But where we see a growth in this extremism is in West Africa,” she said. “So the Sahel region of West Africa, starting with Nigeria, Niger, Mali, Burkina Faso, even countries like Northern Benin and Togo – countries that maybe we would have difficulty finding on the map, but it’s a huge area.”

Reports of attacks come in from Nigeria now on an almost weekly basis, she said, and there are about 2 million internally displaced persons in Burkina Faso.

She clarified that some of the trouble comes from bandits and those seeking to profit from kidnapping. And jihadists attack not only Christians, but anybody who doesn’t share their ideology, which is opposed to anything connected to the West.

“And they equate Christianity with the West, even though we know it didn’t start in the West,” she said. “But there certainly is, I believe, an anti-Christian move really to drive the Christians out of a lot of these countries.”

The life-giving cross

Nevertheless, Christians living under conditions such as these often seem to live stronger lives of faith than before:

“Isn’t it the mystery of our faith somehow that God gives us this cross to carry but somehow it strengthens us in our faith,” Lynch pondered. “And I’ve been so privileged over the years to meet people in different countries where they’ve shown themselves to be really strong in their faith. … These people don’t abandon their faith. They really see Christ as their salvation.”

She pointed to the tiny Christian community in the Gaza Strip as an example, where 2 million Palestinians have been under bombardment since last October’s Hamas attack on Israel. ACN reported the other day that some 30 members of that Christian community have died in the war. A religious sister there told Lynch recently that the community is having trouble finding food and clean water.

“But they move forward in this Lent, carrying their cross with a certain joy and knowing that God will not abandon them. I think we’re very lucky to have a faith where, in the suffering of Christ, in the cross, we can still see the hope of resurrection, that it didn’t all finish on Good Friday. And that’s, I think, what carries a lot of Christians along who are suffering terribly for their faith.”

Likewise, in Nigeria, the bishops are not afraid to speak out against persecution and a lack of government protection.

“The Church stays with its people,” she said. “It’s always there to help the people when maybe governments, politicians abandon the people completely. They turn to the Church and, well, we do what we do as Christians – we show the face of Christ; we show through charity, through mercy. We help anybody in need.”

Future growth

Lynch said she hopes to see ACN continue to grow, not only in its assistance to Chritian communities that are struggling to evangelize but in the foundation’s advocacy for the suffering Church.

“We have the two reports, the Religious Freedom Report and in the alternate year the report on the persecution of Christians,” she said.

“We would like to grow more and become even more professional at doing that, and to be an important source for our donors, for Catholics around the world, and also, I would hope, for decision makers in governments, that they have reliable, well researched information on what is happening to Christians in countries that are far away and where people don’t have a voice.”

She added, “And I think we are also very good at looking at the signs of the times and what is happening worldwide in the Church and that we can be ready to react quickly to situations like when ISIS invaded the Christian villages [in northern Iraq], we were there three, four days after the refugees, the displaced arrived in Erbil. We were able to react very quickly.

“And our response to the war in Ukraine: We were in the starting blocks because we knew from our partners, our bishops, that it was going to happen and how they had planned to come to the assistance of the people. So we were able to react very quickly to that as well.”

Said Lynch: “I feel very privileged – along the road I’ve met people who have challenged me in my faith and opened my eyes really to the fact of what lengths people are ready to go to, in order to not reject their faith, not to give in and to give up.”