Lenten Campaign 2025

This content is free of charge, as are all our articles.

Support us with a donation that is tax-deductible and enable us to continue to reach millions of readers.

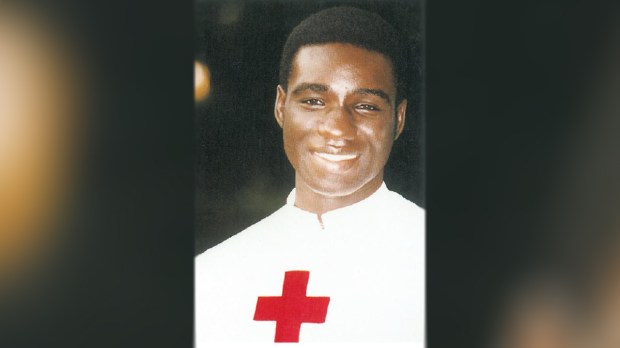

There isn’t an empty seat this Friday in the narrow third-floor courtroom of the Lateran Apostolic Palace. Religious men and women in white and black habits, adorned with the large red cross of the Camillians, have flocked to attend the official opening of the beatification process for Alexandre Toé.

The first step in the Burkinabè’s cause of beatification and canonization was taken in this intimate setting, to the sound of tom-toms and songs. The juridical proceedings to open the cause, presided over by Bishop Paolo Ricciardi, delegated by the Cardinal Vicar of Rome Angelo De Donatis, were admittedly a little dry. But not so the reminder of the short life of Burkina Faso’s first “Servant of God.”

Servant of God Alexandre’s early life

Alexandre Toé was born in 1967 in Boromo, Burkina Faso, to two particularly pious parents, Samuel and Judith. “It was in this family that my faith and convictions grew by leaps and bounds,” he wrote in his spiritual diary.

With his parents as role models, young Alexandre established himself as a bright child at school, helpful at home, and particularly fervent.

It was in high school that he first felt the call to follow the Lord. During a spiritual retreat he attended, he was impressed by the charism of a priest from the Order of Ministers of the Sick, known as “Camillians” after their founder, St. Camillus de Lellis. He came into contact with this congregation and decided to join it in 1987, after graduating from high school.

He continued his training in Ouagadougou, devoting himself intensely to study and the pursuit of his ideal of holiness. His quest took shape first and foremost in prayer, in which he sought to be “simple with the Lord, like a friend at his side,” but also in his devotion to love and fraternal service.

He wrote that “the love we receive makes us exist, but the love we give elevates our existence.”

“A poor Burkinabè in rich Rome.”

But his health weakened, and after his ordination as a deacon, he fell ill with hepatitis, prompting his superiors to send him to Rome in 1991 for treatment and to complete his training. It was as a “poor Burkinabè in rich Rome” that he made this journey, never breaking the bond that united him to his people.

He made his final profession in Rome in 1994, then returned to Ouagadougou where he was ordained in 1995. However, he was sent back to the Eternal City, where he was put in charge of his order’s postulants. He died of cancer the following year.

He passed among us “like a ripe fruit that has left a fragrance of holiness,” says Fr. Pedro Tramontin, Superior General of the Camillians, with emotion. He praises the intrinsic link to suffering of “his short and intense religious life,” entirely given to God and neighbor.

The postulator, a young Italian Camillian priest named Fr. Walter Vinci, emphasized how much Fr. Toé’s testimony “speaks to young people today,” especially the many African students who come to Rome for training.

“He didn’t do anything extraordinary, but he lived the ordinary in an extraordinary way,” says Fr. Vinci.

The pride of the people of Burkina Faso

In the presence of the Archbishop of Ouagadougou, Prosper Kontiebo — also a Camillian religious — several Burkinabès came to the opening of the cause. Such was the case of the Camillian provincial of Burkina Faso, Fr. Pierre Yanogo, who recalled this “very simple, joyful, and determined companion in his vocational discernment” with whom he had the good fortune to rub shoulders in his youth.

The event even had an echo in the “country of men of integrity” (the meaning of the name Burkina Faso) where the ambassador to the Holy See, Régis-Kévin Bakyono, is currently based. The opening of Fr. Toé’s case “is a source of pride for the entire Burkinabè people,” he says, praising the testimony of a man who “devoted himself body and soul to the service of the sick” and his enduring attachment to his country.

Going forward, the procedure will include an investigation to establish a file on Fr. Toé in order to prove his “heroic virtues.” He will then be considered “venerable,” and subsequently, if a miracle is recognized, blessed. A second miracle would eventually lead to his canonization.

Burkina Faso is a majority Muslim country (about 65%) but with a notable Catholic minority of some 20% of the population. Some 10% of the population professes indigenous beliefs.

Fr. Toè’s native Diocese of Ouagadougou has over 1M Catholics, served by around 280 priests, giving them a Catholic-per-priest ratio of 3,852.

By comparison, the Archdiocese of Seoul, South Korea has about 1,400 Catholics per priest. The Archdiocese of New York has about 2,300 Catholics per priest. The Archdiocese of Mexico City has about 3,400 Catholics per priest. The Archdiocese of Kinshasa in Democratic Republic of Congo has a whopping 10,600 faithful per priest.