Lenten Campaign 2025

This content is free of charge, as are all our articles.

Support us with a donation that is tax-deductible and enable us to continue to reach millions of readers.

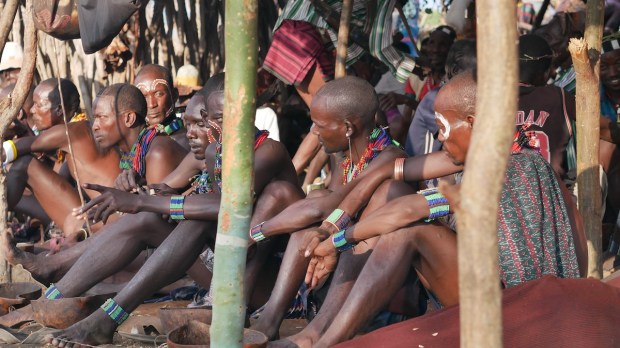

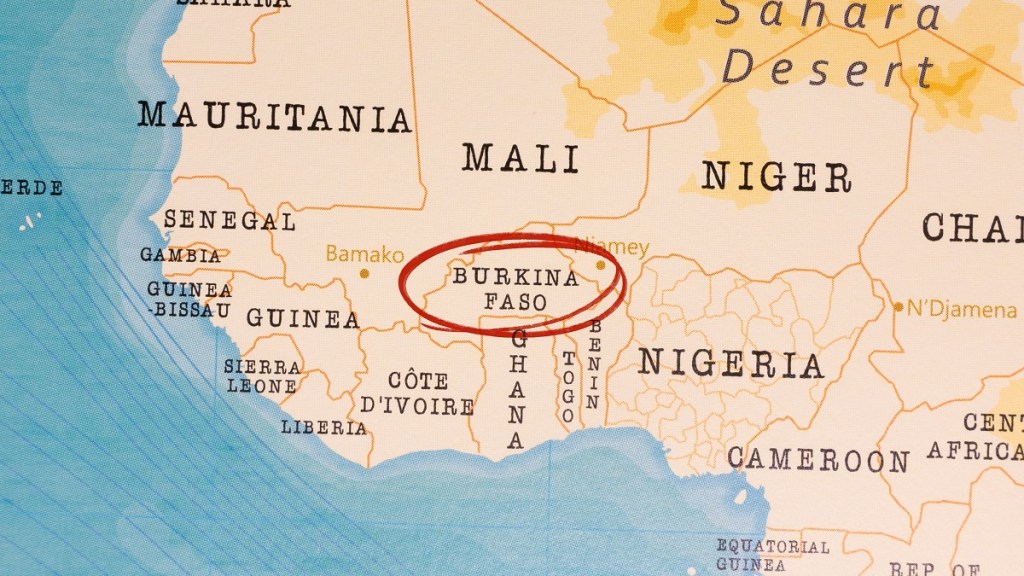

The way a bishop from Burkina Faso describes it, the modus operandi of Islamist groups that are attacking Christians in his country is similar to what has been experienced in other parts of Africa. Marauders come into a village on motorbikes, gather people in the center of the village, and give them parameters by which they should live. Only Islam should be practiced, they tell the people. Certain foods should not be eaten and certain clothes not worn. Women’s faces are to be covered. Men are to grow beards.

In some places, they might be more lenient: Christians can pray in their churches, but there is to be no catechism of children.

Those who don’t agree should leave, they often say. Sometimes, to intimidate people into conformity, a man will be plucked from the crowd and shot dead on the spot. Sometimes the attackers give villagers 48 hours to leave the village.

Such attacks in the former French colony in west Africa started around 2015. Already there are martyrs, said Bishop Justin Kientega of the Ouahigouya Diocese in Burkina Faso’s northwest. In one place, a Marian procession was attacked, resulting in several deaths. Many catechists have been killed or kidnapped. A priest presiding at Mass was killed. Another was kidnapped “many years ago, and we don’t know where he is.”

Bishop Kientega, 64, addressed journalists and others in an online press conference Wednesday organized by Aid to the Church in Need.

“We don’t have problems with Muslims”

Indeed, many Christians are resisting the pressure to give up their faith, refusing to remove the crosses they are wearing, for example, Bishop Kientega said.

“They always try to find other ways to live their faith because they are convinced of their faith. So they always find ways to pray.”

The latest horror occurred this past Sunday, February 25, when 47 people were gathered in a church in Essakane, in the Diocese of Dori.

“The faithful were gathered for prayer with the catechist, because we don’t have priests everywhere,” Bishop Kientega said.

In the end 15 people were dead – mostly men, according to Kientega.

The bishop said that in general he doesn’t know who the attackers are or who is backing them.

Aid to the Church in Need said that the violence in Burkina Faso can be seen as part of a wider conflict that involves several countries in the Sahel region, including Mali, Chad, Niger and Nigeria.

Also on Sunday, a mosque was attacked, apparently by the same set of terrorists. It might be that the Islam practiced there was not radical enough, in the view of the terrorists. Bishop Kientega said that most Muslims in his country are moderate, and some families even send their children to Catholic schools, where they take part in prayers.

“We don’t have problems with the Muslims,” the bishop said. But the terrorists are radicalized.

“We ask ourselves: Who is supporting them? Who is giving them money?” he said. “The big question is why? Why are they killing and kidnapping? Why are they taking the goods of the people? Why are they burning villages?”

Young people lured by promise of work

Speaking in French, through a translator, the bishop said that most of the time the attackers are young people who are “instrumentalized” and are taking drugs. Most of them don’t have work and are lured into this movement by people promising them jobs.

In a May 2021 Factsheet, the United States Commission on International Religious Freedom said that over the previous five years, violent Islamist groups had gained ground in the central Sahel region of West Africa.

Like other countries of the Sahel, Burkina Faso is a Muslim majority country, with 62% of its populace following Islam — mostly of the Sunni variety.

“Both Islamic State and al-Qaeda affiliated armed groups control territory and conduct attacks in the tri-border region between Mali, Niger, and Burkina Faso,” the Factsheet said. “Among these groups, Islamic State in Greater Sahara (ISGS) and Katiba Macina are responsible for grave violations of international religious freedom in their areas of control, including executing individuals based on their beliefs and imposing a strict interpretation of Shari’a (Islamic law) on Sahelian citizens.”

Bishop Kientega said that state authorities are doing their best to help people, organizing convoys to bring food into towns and villages that were affected and to “ensure the security of the people.”

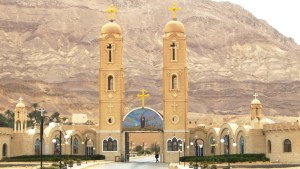

How the Church is responding

The Church, he added, is responding to the crisis in a number of ways: adjusting the schedule of Masses (moving Midnight Mass to the afternoon, for example) or using radio to proclaim the Word of God. In cities, the Church tries to welcome those who are displaced from their villages.

It also works on ways to help people get out of poverty, “because poverty is a ground where this terrorism will grow.”

Kientega said that the presence of the Church in the midst of the troubles is a sign of hope for many people, and he has heard even from leaders of indigenous religions express their appreciation. One told him, “We are happy that the priest stayed, because the priest is a strength for us. All of the help that the parish priest has he shares with everyone, without distinction: Christians, Muslims, people from the traditional religions.”

In some villages the Catholic rectory has become “the house of everybody,” the bishop said. People go there seeking assistance. “Some people even want to get crosses because it is a sign of hope.”

“The main thing is to pray that the Lord will touch the hearts of these people,” he concluded, “so they may be converted.”