In the autumn of 1940, an 18-year-old named Marcel was walking with his dog, Robot, outside a French village when he spotted a fallen tree. Beneath the tree’s exposed roots was a hole that led into a cave. Marcel entered it with three of his friends.

The young men were stunned to discover paintings of strange animals inside the cave – including images of prehistoric deer with enormous antlers, bison, and an extinct species of woolly rhinoceros. The figures all possessed a primitive, magnetic beauty.

Lascaux Cave was later determined to be at least 17,000 years old. Older cave paintings and figures carved from mammoth tusks also exist, dating back 40,000 to 65,000 years. It seems that for most of humankind’s existence we have created and cherished art.

What is art?

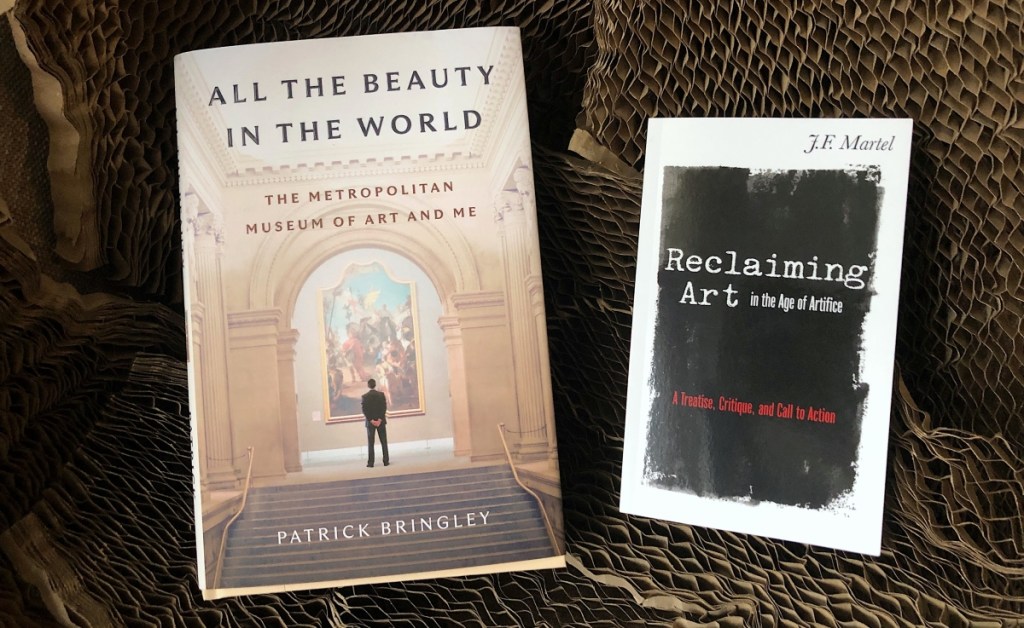

We might start by asking, what is meant by the word art? Author Patrick Bringley has a straightforward answer, proposing that art is “something that is better than it has any right to be.” For 10 years, he worked as a guard at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, an experience he shared in his acclaimed book, All the Beauty in the World.

Bringley spoke at a New York Encounter panel on February 17 titled “What beauty can do to the soul.” The former museum guard recalled being surrounded by objects made with “more care and skill and diligence … than we would have any right to reasonably expect.”

In need of the useless

It is the very uselessness of art that makes it so necessary, added J.F. Martel, lecturer, host of the Weird Studies podcast, and author of Reclaiming Art in the Age of Artifice. Martel said that art “pulls us out of the pragmatism that would insist that everything we do has to a have a use.”

This sense of art as something that transcends the pragmatic can be traced all the way back to caves like Lascaux and the even more spectacular Chauvet Cave in the same region “… where you find ancient artworks that were apparently made for no one to see because they’re in such deep and difficultly accessed recesses of the cave.”

Using physical materials like hair, bones, and minerals that had previously been utilized as survival tools, the first artists repurposed them. They took “something that has a very clear causal function” and gave it a “new function.” Our ancient ancestors needed stone tools in order to survive; not so, carvings and cave paintings. These early artworks brought something new into the world in response to a human thirst not for possession, but contemplation and communion.

Something “fundamental”

What then is the purpose of art? For Bringley, art exists for its own sake. It is an encounter with something “fundamental.” Looking at something truly beautiful gives one a feeling akin to “a bird fluttering in your chest.”

As a guard at the Met, he saw countless visitors have this experience while standing in front of paintings:

I would see someone approach a picture and they clearly felt that the thing was beautiful. And you could almost feel them being sort of infused with this thing…

Objective beauty

Furthering the point, Martel brought up the philosopher Immanuel Kant:

(Kant) said that the experience of beauty is paradoxically probably the most subjective experience (…), but it manifests itself as an objective fact. You experience beauty as something that’s outside of you, something that’s utterly other.

A work of art “elicits from us a kind of evangelizing response. We want to tell other people about it.” Martel gave the example of going to see a beautiful film by yourself. When you leave the theater “you’ve got to tell someone about it” so that they can also experience this film “that’s there, that’s waiting for people.”

Like the poet and artist William Blake, Martel proposed that “beauty is the quality of things seen for what they really are.” He explained:

If we could see without the veil of utilitarianism, of habit, of reflex — if we could just see the world as it is — perhaps it would all strike us as being sublimely beautiful. Maybe art is just a matter of framing little bits of the world and polishing them a bit so that the beauty that was inherently there can be available to others.

Looking at art

Bringely said museum visitors may benefit from becoming “more naïve” when looking at works of art. Setting aside all the information gleaned about an artwork from textbooks, etc., he suggests having “an element of passivity in yourself and later you can then bring your intelligent mind to the process.”

He added: “Give this thing the space to operate on me, to sort of work on me. It’s a never-ending process.”

The entire one-hour conversation between Patrick Bringley and J.F. Martel, moderated by composter Jonathan Fields, can be viewed below.