At some point during a historic pilgrimage to the Holy Land by the Pope of Rome and the Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople, members of the media approached the patriarch, Athenagoras, asking, “Why have you come to Jerusalem?” To which he replied, “To say ‘Good morning’ to my beloved brother, the Pope. You must remember that it’s been 500 years since we last spoke to each other.”

Indeed, the last time a Roman Pontiff and the Patriarch of Constantinople met was in 1438, at the Council of Florence, an attempt to end the Great Schism that had occurred in the 11th century. After Florence, there ensued centuries of what a Catholic priest involved in ecumenism calls an “icy silence.”

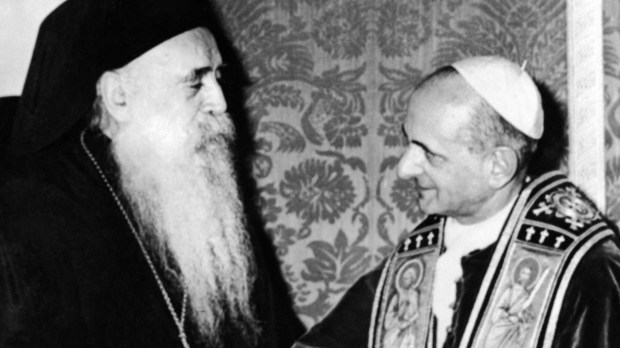

But on January 5, 1964, Pope St. Paul VI met Patriarch Athenagoras on the Mount of Olives in Jerusalem. On this 60th anniversary, their respective successors, Pope Francis and Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew I maintain a close friendship, and an international theological dialogue between the Catholic and Orthodox Churches can look back on decades of growing mutual understanding on the road to a hoped-for restoration of full communion between the Churches.

It was the 1964 pilgrimage to Jerusalem that opened the door for such a formal dialogue.

Paul VI was about six months into his papacy when he announced his intention to make a pilgrimage to the Holy Land. The trip would make him the first Roman pope to use air travel, and the first in over 150 years to travel outside Italy.

“When the Ecumenical Patriarchate in Istanbul caught wind of the fact that the Pope was planning to go to Jerusalem and to the Holy Land, Athenagoras announced that he intended to go as well, in order to meet the Pope,” said Fr. Ronald G. Roberson, CSP, former associate director of the Secretariat for Ecumenical and Interreligious Affairs at the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops. “So the initiative really came from the Greek Orthodox side.”

When Athenagoras arrived at the residence of the apostolic delegate in Jerusalem, where the Pope was staying, Paul descended a stairway, and the two spiritual leaders met at the bottom.

“According to an eyewitness, with tears in their eyes, they spontaneously opened their arms and embraced one another in Christ,” Fr. Roberson told Aleteia. “They held each other tightly as seconds went by full of intense emotion. They then went into the reception hall, where two identical chairs had been prepared for them. They sat together, just the two of them, and spoke privately for 14 minutes. With that, the centuries of silence was broken and a new point of departure began for a new Christian Era.”

Paul VI returned the visit the following day to Athenagoras, who was staying at the residence of the Greek Patriarchate of Jerusalem. “This time, the two men greeted each other as if they were old friends,” Fr. Roberson said.

Rocky road

The priest said that recent historical investigations have revealed much more about the encounter. “In fact, it now appears that Patriarch Athenagoras’s commitment to reconciliation with the Catholic Church was stronger than we knew at the time. Recent research in the archives of Cardinal [Johannes] Willebrands [president of the Pontifical Council for the Promotion of Christian Unity] has revealed that in 1969, the patriarch expressed the desire to concelebrate the Eucharist with Paul VI.”

Cardinal Willebrands told the patriarch that Paul had said, “I would be willing to travel to the North Pole to meet the patriarch and concelebrate with him,” Roberson related. “Athenagoras responded, ‘It is not necessary to travel to the North Pole. St. Peter’s Basilica will do just fine.’”

And yet the historic meeting and what came about because of it were not at all guaranteed. Fr. Radu Bordeianu, an Orthodox priest who teaches theology at Duquesne University and is a member of the North American Orthodox-Catholic Theological Consultation, said the road to Jerusalem was quite a rocky one for both Rome and Constantinople, going back to the planning stages for the Second Vatican Council. Rome wanted to invite non-Catholic observers to the Council, and in order to invite Eastern Orthodox observers reached out to the Patriarchate of Constantinople – considered primus inter pares.

Constantinople started working towards a response to that invitation in September 1961, but a pan-Orthodox conference on the Island of Rhodes apparently reached a consensus that such a response required unanimity on the part of all the autocephalous Orthodox Churches.

The Russian Orthodox Church, however, was not entirely forthcoming.

“Moscow – at that time, remember, it was during communism – regarded Patriarch Athenagoras as an American appointed tool, because Athengoras did spend some time in the United States [as Greek Orthodox Archbishop of North and South America],” Fr. Bordeianu told Aleteia. “And basically, there was this ideological war between Moscow and the Eastern Bloc and the Western world, which included the Vatican. So the Moscow Patriarchate really influenced a lot of the Churches in its sphere, like Romania, Bulgaria, Serbia, Georgia, not to send observers.”

The Vatican, he continued, became dissatisfied with the lack of persuasive power of Patriarch Athenagoras with other Orthodox Churches, “which is really not fair because the Orthodox Churches are, to use a technical term, autocephalous.” There was only so much that Athenagoras could do to get other independent Churches on board; he couldn’t order them to cooperate.

Nevertheless, the Vatican initiated dialogue with several other Churches without the assistance of Athenagoras. Cardinal Willebrands traveled to Moscow, and after Athenagoras announced that no Orthodox Church would send observers to the Council, two Russian Orthodox observers arrived in Rome soon after the opening of the Council in 1962.

“You can imagine the public humiliation that Athenagoras felt, because he announces publicly on behalf of the entire Orthodox [world] that Orthodox observers aren’t coming, and in fact the Vatican and Moscow worked behind his back, and observers are coming,” Fr. Bordeianu said.

Athenagoras was so hurt that when Paul VI was crowned pope on June 21, 1963, he did not send a congratulatory message or representatives to the ceremony.

“Sister Churches”

Why and how the patriarch recovered from the hurt and humiliation is unclear.

“We do not have precise historical evidence to show what healed the relationship between Athenagoras and the Vatican,” said Fr. Bordeianu. “As far as I can tell from the sources that I read, the election of a new pope (Paul VI) and his desire to repair the relationships had a significant role in that regard. Moreover, the Vatican really wanted Constantinople to send observers to the Council. The Vatican knew that Constantinople occupies the premier place within Orthodoxy and their absence — while Moscow was present — was imbalanced.”

Athenagoras’s voyage to meet the pope in Jerusalem would reinforce “Constantinople’s place as the first in the East or the ‘Second Rome,’ as they like to call it,” Fr. Bordeianu said. “And so now the relationship is going upwards to the point at which the Ecumenical Patriarchate actually sent observers to the last two sessions of the Council.”

Those observers made “significant contributions” to Vatican II, the priest said. Not only that, Athenagoras started making plans, which never materialized, to visit the Council as the head of a pan-Orthodox delegation. In his correspondence to Paul, he referred to Rome and Constantinople as “sister Churches,” a phrase he had used in his correspondence with Pope John XXIII. The expression was used later in Unitatis redintegratio, the Council’s decree on ecumenism.

Then Athenagoras expressed to Paul that they “need to make some more significant gestures towards rapprochement, towards coming together,” Bordeianu said. “And Athenagoras has this initiative to lift the excommunications of 1054. That was a significant issue because 1054 became this symbolic date of the separation between East and West, but Athenagoras says that ‘No, it was between the Vatican and Constantinople. It doesn’t need the approval of the other Orthodox Churches.’ You understand what’s happening here: He’s basically no longer limited by what Moscow wants to say.”

In simultaneous ceremonies in Rome and Istanbul, on December 7, 1965, the Pope and the patriarch lifted the mutual anathemas issued in 1054.

The genesis of that action and the theological dialogue that has been undertaken ever since can be traced back to even before the Jerusalem encounter, to Pope John XXIII, who, as apostolic delegate to Turkey had become enamored of the Byzantine liturgy he experienced in Istanbul. As Paul VI told Athenagoras in the city of Christ’s death and resurrection, “The present meeting was desired from the time of our Predecessor of immortal memory, John XXIII, whom indeed you openly followed with esteem and love, and to him, not without sharp perspicacity of mind, you applied the words of St. John the Apostle: ‘He was a man sent by God, whose name was John’ (Jn. 1, 6).”

Pope John’s death prevented him, his successor said, “from carrying out these wishes of his soul,” a meeting between the Pope of Rome and the Patriarch of Constantinople.

“Nevertheless, the words of Christ: ‘That they may be one,’ uttered again and again from the mouth of that dying Pontiff,” Paul said, “show without a doubt where he looked at one of those goals which were most pressing to him and for the accomplishment of which he offered the long agony of death and his precious life to God.”