I’ve never been in La Sagrada Familia basilica in Barcelona. I’ve only seen it in pictures. For someone who has never physically stood in the nave and watched as the sun painted the stone ethereal colors through the stained glass, who has never looked up close and personal at the riot of imaginative figures carved into the stone that seem to spring up organically from the earth, who has never strained his neck to see the very top of the soaring towers, I’m really, really a fan. I love everything about La Sagrada Familia.

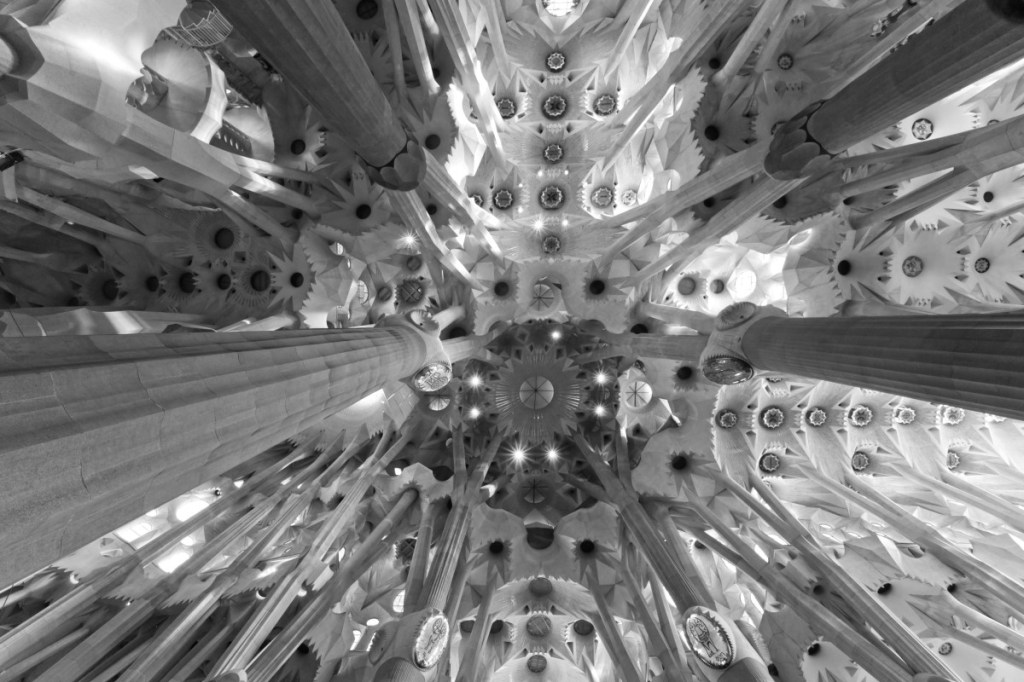

Construction on the church, dedicated to the Holy Family, began in 1882 and still isn’t finished (the main tower will be even taller). There’s enough completed, though, to note that this building, the work of architect Antoni Gaudi, is unlike any other. The sculpture is a riot of living forms. The stone is vibrant and fluid. The great colored windows light up the side aisles in soft green and blue, so the interior is transformed into some hidden glade deep in the forest.

Blurring the lines between earth and sky

I think it’s best to simply let the architecture be what it is and not try to label it, but it’s clear that, even if Gaudi’s work is a unique expression of beauty, he is heavily indebted to the Gothic style. Throughout his work, he plays with light and form. The interior soars, reaching to the heavens. Sagrada Familia blurs the lines between earth and sky, rigid stone form and organic growth, seriousness and whimsy.

Perhaps the idea of Gothic brings to mind the dark ages, oppressive feudal lords, and overbearing clergy. If so, then Gothic brings to mind an architectural style mired in the primitive, unimaginative past, a church edifice designed only to intimidate peasants and make God seem distant. If all this is true, it might seem odd to identify Gaudi’s work as a continuation of the Gothic idea. His modernistic, playful approach seems worlds away from the era I was taught in grade school was the low-water mark of western civilization.

A Gothic celebration

What I was taught in school is wrong. The medieval era, during which the great gothic cathedrals were built, was a wonderful time to live in Europe. A closer look at the churches makes this abundantly obvious. The Gothic style isn’t dark and moribund. Quite the opposite, it’s a celebration of light and life, new progress and happy communities. Towering glass windows represent technological breakthroughs in architecture. The finely proportioned buildings represent a wealth of knowledge in the area of sacred geometry, stonework, and art. The churches aren’t drab and gray. They’re a riot of clashing patterns and colors.

Most of all, the joy of Gothic can be observed in the stone figures carved into the tops of pillars, in corners, and the exterior facade. The carvings, made by anonymous masons, are thoughtful and intricate. They’re also quite amusing. Looking at the talent and whimsicality that has gone into creating the great gothic cathedrals, it’s impossible to imagine they were made by a people who were unhappy. The same whimsicality and joy is stamped all over La Sagrada Familia. In this sense, it’s a direct descendant of the Gothic style.

Living nature carved in stone

In particular, Gothic loves natural forms. Gothic cathedrals are full of pictures and carvings of vines, flowers, and trees. They combine a perfect balance of harmony and form with expressive, over-the-top organic wildness. Gaudi inherits this love of nature and pushes it to the maximum, which is why La Sagrada Familia looks to be so alive you can that, even from looking at the pictures, I almost sense the stones are growing and putting out new leaves and flowers, blossoming a gargoyle here and a saint there.

G.K. Chesterton, when observing this same phenomenon at the cathedral in Lincoln, England, described it as a visual representation of the Church on a march. “The graven foliage,” he writes, “wreathed and blew like banners going into battle.”

Gaudi didn’t carve arboreal beauty into his work for no reason. His architecture speaks through natural forms because, he says, “Anything created by human beings is already in the great book of nature,” and, “Man does not create… he discovers.”

Returning to the origin of beauty

In La Sagrada Familia, everything is providential. Its originality consists of returning to the origin of beauty, which is found in flowers, trees, sunsets, mountains, and oceans. Gothic is an expression of beauty that reaches all the way back to the Garden of Eden. The churches are a reflection of Paradise.

How appropriate, then, that Gaudi’s basilica is dedicated to the Holy Family. The family is life. It is chaos. It is unbridled joy. Families are Gothic, organic expressions of human growth, creativity, and the beauty of existence. Each family is a little paradise, a garden that grows as it will, a profusion of beauty stretching higher and seeking the heavens.