In the opening theme of Fiddler On The Roof, titled Tradition, a young man queries a Rabbi about an appropriate blessing for the Tsar. The Rabbi amusingly responds, “A blessing for the Tsar? Of course! May God bless and keep the Tsar … far away from us!”

Similarly, within Catholic tradition, blessings encompass a wide array of requests and items. Indeed, the Rituale Romanum includes blessings for virtually everything and anything, from beer to lard (or bacon), from cheese to wine.

The etymology of the word blessing is as interesting as it is revealing. The modern English word “bless” derives from the Old English term blaedsian. The term, scholars agree, referred to the act of making something “sacred” (that is, set apart) through sacrificial customs, often involving the marking with blood. The practice is linked etymologically to the Anglo Saxon blōd – that is, blood.

The evolution of the term took a transformative turn during the Christianization of Old English, where the Latin term benedicere, meaning “to speak well of” — bene (well) with decire (to speak) — was “translated” into blessen. This linguistic shift influenced the modern meaning of bless and changed the “sacralizing” connotations of the pagan blaedsian into the more nuanced “speaking well of” and, by extension, “wishing well.” Obviously, Christian preaching played a pivotal role in shaping these linguistic nuances.

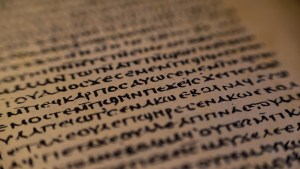

In the Bible

Blessings are more than linguistic matters, but words matter. In Rabbinic Judaism, berakhot (blessings) are recited during specific moments – especially before and after consuming food. These blessings serve to acknowledge God as the ultimate source of all blessings. The recitation typically begins with the words, Blessed are You, Lord our God, King of the universe. Expressing gratitude to God is seen as the most essential aspect of acknowledging the divine provider.

The rabbinic concept of berakhot is also integral to the teachings found in the Gospels. In Christian Scripture, blessings also point at the recognition of God’s presence in everyday life and, as importantly, in human action. But the Gospels use two different words for “blessings” and “blessed.”

One of the most renowned passages where blessings are prominently featured is the Sermon on the Mount, as recounted in the Gospel of Matthew (Matthew 5:1-12). In this sermon, Jesus presents a series of blessings known as the Beatitudes. The word used in these passages is makarios – the closest word in Greek to the English happy. These blessings describe the qualities and attitudes that are not only pleasing to God, but that directly proceed from Him – thus bringing joy to the world. The Beatitudes highlight a counter-cultural perspective, emphasizing spiritual values over worldly success as the source of all joy.

Throughout the Gospels, Jesus is often portrayed as bestowing blessings upon individuals, announcing God’s grace. In these situations, a different word is used. His interactions with the marginalized, the sick, and the outcasts reflect a compassionate disposition, and through his words (blessings) and actions (performative blessings, if you will), God’s presence is revealed – or, even better, recognized.

This recognition of the divine presence naturally leads the believer to praise God. If the Hebrew berakhot derives from the word barak (meaning to kneel and, by extension, “to praise”), the Greek eulogos literally means “to speak well of.” The Latin benedicere is a direct translation of this original Greek. In more ways than one, preaching is equivalent to blessing: Those who have seen God’s presence (those who are witnesses) cannot but speak well of what they have seen.