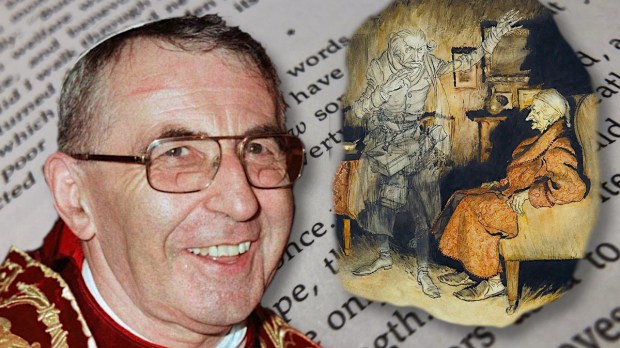

During his brief pontificate, John Paul I was known as “the smiling pope.” His characteristic warmth is evident throughout the collection of letters published as Illustrissimi (To theIllustrious Ones).The letters were written between 1971 and 1975 for the Catholic newspaper Messaggero di S. Antonio when he was still known as Cardinal Albino Luciani and served as the Patriarch of Venice.

There were 40 letters in all, written to historical figures like Hippocrates, to saints like Teresa of Avila, and even to fictional characters like Pinocchio. There are also letters to famous authors. In fact, the first letter in the collection is addressed to Charles Dickens, the author of Oliver Twist and Great Expectations.

Why Dickens? As he explains at the beginning of the letter, John Paul I had loved Dickens’ Christmas Books since he was a boy. “I … enjoyed them immensely,” he wrote, “because they are filled with love for the poor and a sense of humanity.”

Dicken’s love for the poor

Charles Dickens (1812-1870) knew the plight of the poor firsthand, as the letter points out. When Dickens was just 12, his father was forced to enter a debtors’ prison. In order to support his family, young Charles had to work in a blacking factory – which produced bottles of liquid shoe polish. For 10 hours a day, Dickens would seal the pots of paste-blacking and stick labels on them.

The months that Dickens spent in these inhuman conditions made an indelible mark upon him. Many of the scenes and characters in his fiction have their roots in the misery that Dickens witnessed and experienced in Warren’s Blacking Warehouse. “This is why all your novels are populated by the poor,” the future pope explains. Later he remarks:

These are the oppressed, and all of your compassion is poured out on them. On the other side are the oppressors, whom you stigmatize, your pen driven by the genius of wrath and irony, capable of shaping typical characters as if in bronze.

The ghost that fascinated a pope

It is interesting that the character that John Paul I seems most impressed with in A Christmas Carol, Dickens’ most famous yuletide story, is not Ebeneezer Scrooge, but his ex-partner, the ghost of Jacob Marley. He recalls the chilling speech that Marley gives when he explains to Scrooge why he is bound in heavy chains:

Business! Mankind was my business. The common welfare was my business; charity, mercy, forbearance, and benevolence were all my business … Why did I walk through crowds of fellow-beings with my eyes turned down, and never raise them to that blessed Star which led the Wise Men to a poor abode? Were there no poor homes to which its light could have conducted me!

Christmas is about the forgotten

John Paul I’s letter to Charles Dickens is a wakeup call that there can be no true celebration of Christmas without an active, engaged “love for the poor.” Our Lord was born in a manger, and He also said that “whatever you did for one of these least brothers of mine, you did for me.” Like Dickens, we are called to respond to the most vulnerable and forgotten in our world.

Though conditions have improved for many since the 1800s, the future pope tells Dickens that poverty still exists in 1971 (the year the letter was composed), though in new forms. Society suffers from dwindling resources, a damaged environment, and a growing “fear and concern” about where the future is headed. That rings just as true 50 years on.

A boat on rough seas

The letter ends with a call to solidarity and trust in God that must have resonated with Pope Francis over the years:

We are all in the same boat, filled with peoples now brought closer together both in space and in behavior; but the boat is on a very rough sea. If we would avoid grave mishaps, the rule must be this: all for one and one for all. Insist on what unites us and forget what divides us.

And then John Paul I comes back to the wretched figure of Jacob Marley who “wished that the Star of the Wise Men might illuminate the houses of the poor.” Our world, a “poor abode,” remains in need of illumination. In this reading of Dickens’ classic story, A Christmas Carol is not just a holiday ghost story, but also a prophetic call to action and a prayer.

Editor’s note: Aleteia will be looking at the letters published in Illustrissimi in the coming weeks.