The lily-covered pond in his garden inspired Claude Monet over the course of his life to make almost 300 paintings. One of those water lily paintings has subsequently made its way to the wall of the St. Louis Art Museum, where I’ve spent many hours looking at it. Entrance to the museum is free, so it was easy for an art-obsessed teenager to visit often. I would stand and look at the painting, lost in wonder.

The canvas is about 13 feet in width. Standing in front of it, the scene filled out past the edges of my vision. All I saw was the water, the lilies, the reflections. The rest of the world was pushed from sight. The painting has no horizon, no boundary. It’s the same sensation as lying down, looking up into the night sky, and feeling you’re about to fall upward into the stars.

Popularity and dismissal

There was a time when it seemed like a print of the water lilies was pinned to the dorm-room wall of every college freshman. Monet has enduring popularity because his art is so very beautiful. The images are easy to love, but as often happens, there was a backlash. Art aficionados, for the very reason of this popularity, dismiss Monet as un-serious.

While he was alive, Monet was aware of this phenomenon. He knew that his work, which in his youth was considered groundbreaking, had come to be dismissed by subsequent art movements. As the 20th century took hold, artists and critics became cynical and jaded. They began to like highly theoretical, scandalous, ironic art. Monet, meanwhile, was dismissed as a washed-up has-been who painted pretty pictures of gardens.

There’s far more to Monet, though. The paintings speak for themselves. The way to understand the water lilies, as is the best way to understand any painting, isn’t to extract and verbalize a high-level philosophical theory from the work. The best way to understand a painting is to look at it.

The best way to understand a painting is to look at it.

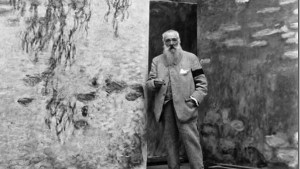

Monet the man and artist

If we had no backstory, if we didn’t know who Monet is or why he painted the water lilies, we would still fall in love with the paintings simply by looking at them. But I want to say more, because the water lilies have a fascinating history that adds to the depth of our appreciation.

Monet first burst onto the Paris art scene in the 1860s. At the time, the established artists didn’t care for his experimental method of painting, which came to be called Impressionism because it emphasizes the play of light on form, creating impressions of light-filled, beautiful moments. Critics didn’t think the paintings looked finished, they were mere impressions. Over the decades following, however, Monet became immensely popular.

After a career that spanned decades, Monet’s popularity began to wane. In the beginning, his work was considered too experimental, but by the end he was considered out-of-date and uninspired. He even claimed himself that he was tired of art and only wanted a nice, painting-free retirement in his country house in Normandy.

Worse yet, by the year 1914 when he was 73 years old, his beloved wife had recently died, his son died, he was going blind from cataracts, and Europe had descended into a vicious war.

The water lillies

This is when the really big paintings of the lilies start. Off and on for decades, Monet had been painting his garden, including the water lilies that he himself had planted. But now, in his old age, in the face of personal disappointment, the death of loved ones, failing health, and a nation in the throes of immense violence, his canvases become bigger than ever. It’s almost as if the lilies (some of the new paintings forming a series intended as a war memorial) expand and grow until their serenity overcomes all the pain in the world. The delicate beauty of his lilies is how Monet reacts to the ugliness life had thrown his way.

In his garden, Monet painted a limitless new world. “What is lost in life we find in art,” he said, and the paintings are his discovery of Paradise — a landscape of water gently floated with flowers, curving willow branches, and reflections of clouds. The lack of definition in the landscape is intentional, creating, “the illusion of an endless whole, of a wave with no horizon and no shore.”

It’s almost as if the lilies … expand and grow until their serenity overcomes all the pain in the world.

A weakness transformed into beauty

The cataracts that were slowly blinding him tinted the world with a yellowish tone. Monet compensated by adding blue pigment to his paint mix, which is why the paintings from this period take on a blue-green tone. His failing eyesight, a weakness, is present in the paintings visually as a limited color palette, but through the skill of the artist the weakness is transformed into beauty.

The light suffusing the painting isn’t sentimental. Yes, the paintings are beautiful to look at, but that doesn’t mean they don’t possess deep, heartfelt meaning. In Europe, war was tearing the landscape to pieces. Rural fields were scarred with trenches, trampled to mud, and the trees were blasted to rattling skeletons by unrelenting artillery barrages. In response, Monet turns to his garden.

Heaven reflected

His artistic gaze goes to the soul, to the peace underneath all things that passes understanding. The lilies float on the water, fleeting and yet somehow permanent. The surface of the water and the shape of the lilies is only suggested as the physical forms give way to interior form. The artist looks down to the water and sees a reflection of Heaven.

We do not know why suffering happens. All we know is that we carry suffering and peace and sadness and happiness with us everywhere we go. This is what it means to be human.

This world we have been given is a foretaste of Paradise. God is planting his garden. At times we feel like seeds dry and cracked, captive in damp soil. At other times we float like flowers on a glassy blue pond. Monet accepts it all and transforms it to beauty. Even when looking down into the water, we’re looking up.