Lenten Campaign 2025

This content is free of charge, as are all our articles.

Support us with a donation that is tax-deductible and enable us to continue to reach millions of readers.

Life in 16th-century Venice was not easy. After years of expansion, the Republic of Venice was starting to lose power in the region. The city was also hit by one of the worst plague epidemics in history. During a time of crisis, many people found strength by praying in front of a painting believed to have miraculous attributes.

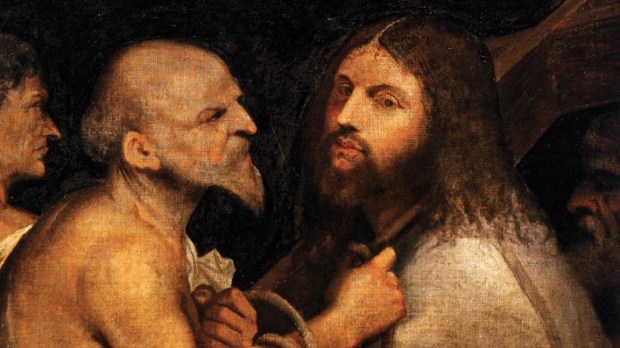

Attributed to Titian or Giorgione, “Christ Carrying the Cross” was praised by art historians like Vasari for the “great powers the painting had over its public.” The painting — currently kept at its original location in Venice’s Scuola Grande di San Rocco, the building that hosted the seat of the Confraternity of St. Roch — was one of the first examples of a “close-up” style of representation.

Jesus is portrayed with the cross on his shoulder on his way to Mount Golgotha while an executioner holds a noose on his neck. The two main subjects are rendered with a sfumato technique that adds a sense of realism and their vivid colors stand out against the dark background. The painting does not seek to recreate a historically accurate depiction of the moment in which Christ is carrying the cross, but rather to “zoom in” on the two main characters.

The main figures seem to be involved in a dramatic scene that involves the viewer. The executioner tries to grab Christ’s attention, but Christ is looking at the viewer rather than at him.

As noted by E.J.M. van Kessel, Jesus seems to ask viewers to follow him in his suffering. According to van Kessel, it is thanks to this intimate connection between the figure of Christ and the viewer that the painting came to be known as miraculous — by following Christ’s suffering, viewers felt they could count on Christ’s support in their own suffering.

For years, people would come from across Europe to pray in front of this artwork. Pilgrims would pray in the church at a side altar where the painting was hung, lighting candles, making offerings and touching the painting. Accounts of people healed from severe injuries, spared from death sentences, and recovering after dangerous falls were reported. Van Kessel lists at least 17 stories of miraculous healing, of which 14 were related to men suffering injuries after being attacked in the streets.

This was not the only miraculous object held at the Scuola Grande di San Rocco. The seat of the confraternity also held the relic of St. Roch and a wooden crucifix believed to be miraculous. But it was this painting more than anything else that drew people to the confraternity building.

As detailed by Van Kessel, news about God’s healing power for those who prayed before this image soon started to circulate, and copies of the painting were made, including one that ended up as part of the collection of Cardinal Alessandro Farnese.

In the meantime, the reputation attributed to the original work led people to appreciate its creator, probably Titian, as a messenger between God and the people. As Van Kessel notes, the artist was not really seen as an inventor but rather as an “intermediary” who could pass God’s grace to the people.