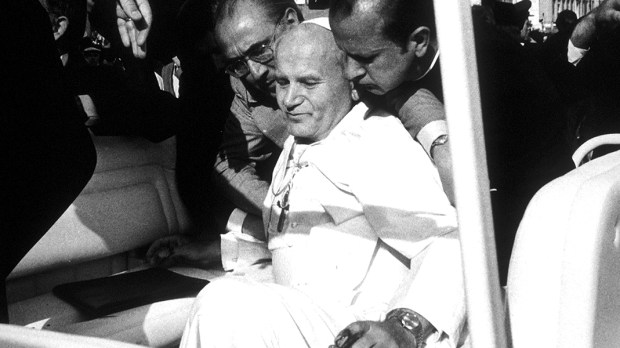

Forty-five years after his election to the See of Peter on October 16, 1978, John Paul II continues to prompt a great deal of historical research, particularly into the assassination attempt that almost cost him his life on May 13, 1981. A conference was held on Wednesday, October 18, at Rome’s Gregorian University by the Polish Institute of National Memory, on the subject of files from the archives of the secret services of several countries regarding this Pope who came from the “Church of silence.”

The attack in St. Peter’s Square was “one of the last convulsions of 20th-century totalitarianism.” This statement by John Paul II himself in his last book, Memory and Identity, published just a few weeks before his death in 2005, opens up vast possibilities for interpreting the scale of the networks set up to try — unsuccessfully — to eliminate the first pope to come from a country governed by a Communist regime.

Going beyond the initial investigation

More than four decades after the assassination attempt against the Pope on May 13, 1981, by the Turkish terrorist Mehmet Ali Agca, there are still many gray areas regarding the forces directly and indirectly involved in eliminating the main spokesperson for opponents of communist totalitarianism.

While in the 1980s the Italian judiciary focused on Mehmet Ali Agca’s personal responsibility, Poland wanted to reopen the case after the death of the Pope. The Polish Institute of National Memory, an institution which was set up in part to analyze the abuses of the regime in power in Poland from the end of the Second World War to 1989, took the lead.

From 2006 to 2014, prosecutors from the Institute carried out a vast investigation to identify the role of the Communist secret services in the attempt to eliminate the Pope. The results, some of which have never before been revealed in such detail, were presented at the above-mentioned conference in Rome along with a book on the topic, published in Italian under the title “Agca non era solo” (Agca was not alone).

Media manipulation and Communist involvement

It shows that numerous agents from the East were involved in the preparation of the attack, as well as in the years that followed, in order to create diversions. A vast media campaign was waged to highlight the link between Mehmet Ali Agca and the Grey Wolves, a far-right Turkish organization, in order to confuse the issue. The East German Stasi was particularly active in this disinformation campaign, notably by sending the Turkish press a forged letter from a Turkish nationalist leader pledging support for Ali Agca.

But it is a fact that the Turkish terrorist, who had escaped from prison in November 1979 after murdering a newspaper editor, was later taken in charge during his stay in Europe by the Bulgarian secret services. This then-Communist country was home to a powerful mafia operating on the border with Turkey, a contact zone between NATO and the Warsaw Pact.

Mehmet Ali Agca also met a KGB agent in Tehran, who later defected to the West. These tangible clues corroborate the theory that this marksman, known for his precision, was recruited by the Communist regimes.

The Polish Pontiff’s enemies envisaged various scenarios, some of which leaked to Western intelligence services, who tried to warn the Pope. The French secret service, which had been informed of a planned attack on the Pontiff as early as 1979, failed to pass on the information to the Vatican.

A Pope “likely to cause many problems” for the Communist regime

Even more troubling are the leads to Moscow. It goes without saying that in 1978, the election of a pope from a Communist country caused astonishment in the Kremlin. A few months later, the irremovable Soviet Foreign Minister Andrei Gromyko — one of the few regime leaders to have worked continuously with every Soviet leader for four decades, from Stalin to Gorbachev — returned shaken from his first meeting with John Paul II.

This experienced diplomat, who had met Paul VI on four occasions, was not likely to be impressed by the Vatican and the figure of the “Pope of Rome,” a relatively distant and anachronistic authority for Soviet leaders, who considered the Catholic Church an outdated and negligible institution.

But Polish archives have revealed his palpable concern about the charisma of this ‘young’ Pope, elected at the age of 58. Traveling directly to Warsaw after his visit to Rome, Gromyko spoke with the Polish Communist leader, Edward Gierek. He described the new Pope as “a healthy, agile man, who has continually taken care of his health,” and is therefore likely to live a long life. He presents him as an “expert” who is likely to “cause many problems in Poland.”

His tone echoes that of the files drawn up on Cardinal Wojtyła by the services of the People’s Republic of Poland before his election, noting the “high intellectual level” and “good tactical sense” of the Warsaw archbishop, whose activities “are ideologically dangerous.”

A direct order from the Kremlin?

Faced with an adversary of this magnitude, the confrontation was not a debate of ideas or a simple intellectual joust. The Soviet leaders understood that John Paul II posed a mortal threat to their communist ideology, and so they engaged in a fight to the death. An analysis of Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev’s personal diary reveals some disturbing facts: between April and June 1981, just before and after the attack on St. Peter’s Square, he met with unusual frequency with KGB chief Yuri Andropov.

On the very day of the attack, May 13, Brezhnev received an African delegation before locking himself away in his office for a long time, alone, as if awaiting important and confidential information, until he left for his personal residence at the end of the afternoon. The attack took place at 5.17 p.m. Rome time, or 6.17 p.m. Moscow time. In the days that followed, Brezhnev met with Gromyko and Andropov. The content of their exchanges remains a closely guarded state secret, but the Soviet leader’s agenda seems to show a certain feverishness in the Kremlin.

In the aftermath of the attack, while the Communist leaders officially sent the Pontiff get-well wishes, the archives show that internal circles of power reacted quite differently. “I can only dream that God will call him back to himself as soon as possible,” said the infamous Polish Minister of the Interior at the time, General Czesław Kiszczak … a cruelly ironic remark from an executive of a regime that advocated atheism!

John Paul II himself “not interested” in knowing more

But the Pope himself, who attributed his survival to Our Lady of Fatima, never sought to incriminate anyone. During his 2002 visit to Bulgaria, he hinted that he had never believed in the existence of a “Bulgarian network” for this attack.

In the 1980s, in a conversation with his friend and compatriot Cardinal Deskur, who was astonished at his lack of interest in developments in the Ali Agca trial, John Paul II delivered a scathing reply. “They don’t interest me, because it was the Evil One who carried out this act. The Evil One can act in thousands of ways. I’m not interested in any of them.”

Through his suffering and his forgiveness of Mehmet Ali Agca, the Pope wanted above all to break the chains of hatred and vengeance, and show the world the radicality of following Christ in martyrdom, absolute trust in God, and non-violence.