I recently sold a guitar that I had owned since I was a teenager. For years I’d held onto it because I was emotionally attached to it. I’ve moved it from house to house over the decades, always keeping it in storage because I have another guitar I prefer to play. I realized, though, that my poor guitar in storage was developing a crack in the wood. I wasn’t playing it enough to maintain it and it was slowly falling apart.

Rather than see it go to pieces, I finally sold the guitar so someone else could care for it and enjoy it. It’s ironic; my desire to keep it was destroying it, but my willingness to part with it will bring more joy into the world.

Possessions sure do have a strange relationship to joy.

An extreme poverty

St. Francis of Assisi ended his life with no possessions whatsoever. He owned a patched brown robe and, well, that’s about it. There’s a whiff of romance connected to the life of Francis, as if he spent his days skipping through the forest, singing with birds and eating nuts and berries. In fact, his poverty was extreme and, in a superficial way, quite ugly.

As G.K. Chesterton writes in his biography about the great saint, “In plain fact he was ready to live on refuse; and it was probably something much uglier as an experience than the refined simplicity which vegetarians and water drinkers would call the simple life.” There’s an inner beauty to the way Francis emptied his hands so he could grab hold of Christ, but this doesn’t change the fact that his renunciation of material possessions went far beyond what seems reasonable.

The fact that Francis died with nothing is surprising because he began life with a great deal. He was born into a well-to-do merchant family and had every material possession a person might possibly want. After his decision to seek extreme poverty, he famously gave away many of his father’s possessions, thereby drawing his ire, before stripping off all his expensive clothing and disappearing into the forest. For Francis, the decision to live with nothing wasn’t forced upon him by unfortunate circumstances. It was a deliberate decision.

Emptied hands and emptied heart

St. Bonaventure believes the renunciation went much deeper than leaving behind material comfort. He calls Francis “the poor man of the desert,” who also desired spiritual poverty. He wanted to live with the constant knowledge that, in relation to God, humans are humble creatures indeed. He wanted not only empty hands but also an empty heart that God could fill with divine love.

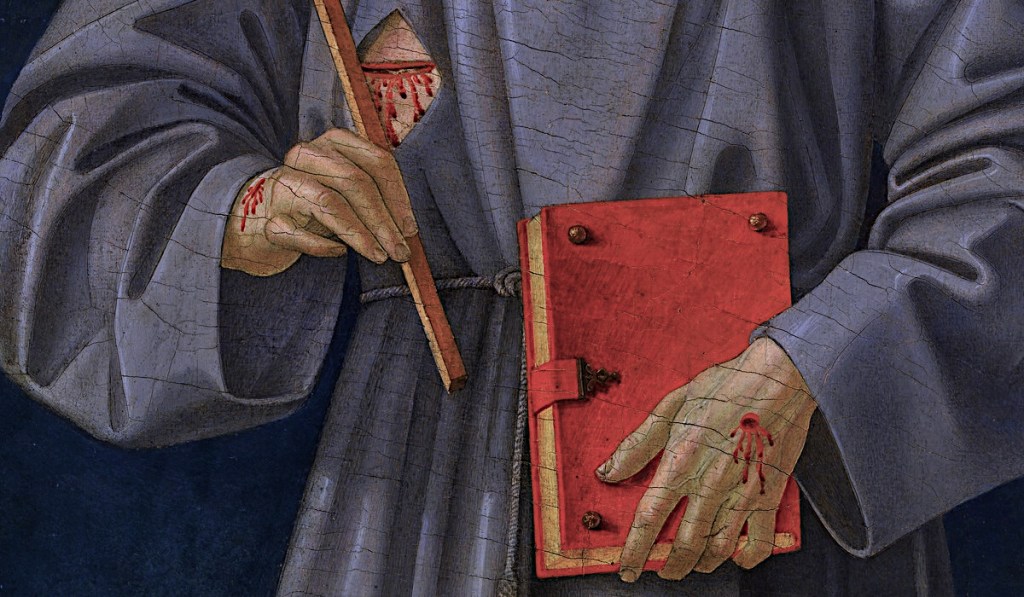

A few weeks ago, on September 14, we celebrated the Exaltation of the Holy Cross. This is the day that St. Francis received the stigmata when, in 1224, he climbed Mount Alvernia for a 40-day fast. There, he saw an angel with six wings descend from the sky carrying the crucified Christ. Bonaventure says that, from that moment until the end of his life, Francis exuded unshakable peace and inner joy.

Why would the ultimate renunciation, the physical pain of carrying the wounds of Christ, make Francis so happy?

Part of the solution to the riddle is that by that point in his life Francis was already happy. He had already given away everything he owned. He was already practicing fasting and penance. These renunciations were the beginning of his happiness. Receiving the stigmata was a broadening and deepening of that same happiness. He had finally been given the opportunity to give himself away entirely. This is why, for the last few years of his life, it was said that his soul shined through his body.

Is renunciation sad?

One myth about doing without possessions or giving up a pleasant-but-bad habit like smoking, or really any type of voluntary renunciation, is that giving things up automatically makes us sad. We have the conception that doing more with less might somehow be “good” or “healthy,” but simultaneously it will make our life more dour.

I remember something as simple in my own life as giving up soda and junk food. I did it because I wanted to be healthier but never expected that I would actually start to enjoy food more because of it. I began to taste a more subtle and broad range of flavors. Now when I drink soda or eat candy, the taste isn’t nearly as good as I remember. Not only am I healthier now, but I’m happier. The same holds true for spending less time on my phone, which has freed me up to read and spend more time with my children, or committing to regular exercise, which at first can feel like torture but is now an activity I genuinely crave.

Chesterton notes a common saying among the Franciscans; “A monk should own nothing but his harp.” He comments on the phrase, writing, “he should value nothing but his song … the song of the joy of the Creator in His creation and the beauty of the brotherhood of men.”

Desiring a greater good

It’s clear that Francis renounced goods not because he wanted to punish himself or had low self-esteem and didn’t think he deserved nice things. He did it in order to attain a greater good. Even though renunciation requires discipline, the end result is great joy.

It’s interesting that Francis has become famous because he responded to a vision in which Christ told him to build the Church. Even as he was doing with less in his personal life, he was becoming, almost accidentally, ever more productive in his public efforts. The less he personally possessed, the more he was able to give to his vocation.

As a deacon, Francis worshiped in beautiful churches that contained expensive marble altars and artwork. No expense was spared for the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass. Even as he spent his days in a tattered robe, his vestments for Mass had intricate embroidery on them. The glorious clothing was a sign of gratitude. He was so happy to be alive, so joyful, that he made his existence a gift to God.

Joy in giving

God deserves our best efforts. Our most prized possessions are for him. As Chesterton points out, “all goods look better when they look like gifts.” This has been my experience, too. The times I’ve managed to break through my own selfishness and be generous with someone else, I experience inner joy.

Perhaps the most personal example is my decision to be open to fathering a large family. My children absorb the bulk of my salary and my time. Without them around I would have more freedom and income for my own use. I would be wealthier and have more possessions, but there is no possible way I’d be happier without them around. My money, given away as a gift for my little ones, has become a source of great joy. Technically, my salary puts me in the middle class, but I know I’m a rich man.

Gaining more by possessing less

So often, we believe that more is more. The more money we have and the more possessions, the better. More experiences, more personal indulgence, and more treating ourselves makes us happier. We’ve even fallen into the trap of thinking that throwing more and more money at social problems is the only way to create a more just society, as if we need more programs, more resources, and more funding in order to make a difference.

Francis changed the world by having less. By having less, he was able to offer more of what really mattered — himself. He offered his love.