Lenten Campaign 2025

This content is free of charge, as are all our articles.

Support us with a donation that is tax-deductible and enable us to continue to reach millions of readers.

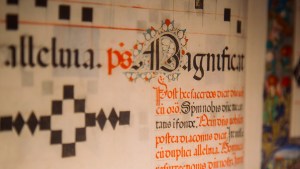

A new data project will soon catalog Catholic plainchant, also referred to as Gregorian chant, from libraries and collections all over the world into a digital platform. Along with the convenience of having so many early musical manuscripts in one easy-to-navigate page, the platform will help researchers trace the evolution of chant and provide insight into the way different cultures approached the Christian faith.

It is an undertaking of musicologist Dr. Jennifer Bain of Dalhousie University, who spoke with the university’s newspaper about the project. She explained that tracking minute changes to the music as it proliferated through different cultures can help to identify how the liturgical expressions (i.e. how they lived and worshiped) of a culture would change over time. This puzzle, however, must be put together using pieces that rarely match.

Bain said there are tens of thousands of manuscripts that bear the history of the Catholic musical tradition and, while many may consist of the same chants, no two works are ever the same. This is because manuscripts of the medieval and surrounding eras were hand-written. Changes to the manuscripts could happen for a variety of reasons, from scribal errors to changes brought about by religious reform, or even to suit a change in dialect.

Missionaries would also make minor changes to musical manuscripts if they felt such changes could help the people they sought to evangelize better connect to the message of the piece. Bain noted that the glorification of God can look different depending on who is penning the text, and this is why a platform in which researchers can place two manuscripts from opposite sides of the world back to back to better observe the evolution of the plainchant is so valuable.

Giving an example, Bain told Dalhousie that when priests first arrived in Nova Scotia, about 400 years ago, they quickly set about translating their plainchant into Mi’kmaq language to bring the Christian faith to the First Nations people of the Northeastern Woodlands. She explained that her research illuminated details about how the Mi’kmaq people adopted Christianity, as well as providing insight into the Mi’kmaq culture and language.

“Thinking about what vocabulary they used to describe these Christian ideas can tell us a lot about the Mi’kmaq worldview. The way that they describe God, and Jesus and St. Anne, and all of these things tells us something about how they understood these spiritual concepts that were being introduced.”

The project is expected to take seven years for a team of 23 co-investigators and 24 collaborators to complete the database. It is supported by a $2.5 million partnership grant from Canada’s Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council, with further funds coming from 20 partner organizations in Canada and around the world who have committed more than $3.5 million in in-kind contributions.