Lenten Campaign 2025

This content is free of charge, as are all our articles.

Support us with a donation that is tax-deductible and enable us to continue to reach millions of readers.

It’s a long, ancient-sounding word, but “hagiography” still has much relevance to current-day faith. Works of hagiography (from the Greek for “writing about the holy,” usually referring to biographies of the saints), most of them composed many centuries ago, have helped to shape our understanding of the saints and enable us to appreciate their sufferings and triumphs.

Along with relating personal backgrounds of saints or other individuals of religious importance, hagiographies tend to emphasize holy personality traits, good deeds, and miracles. Persecution and martyrdom are other frequent elements.

The hagiography genre seeks to idealize its subject matter. Some cases might feel excessive, but many can be powerful and uplifting.

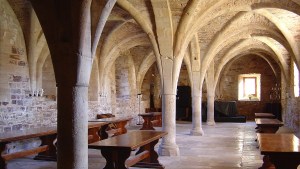

Aside from spiritual inspiration, hagiographies have served to generate interest in a particular region and attract pilgrims to visit local venues of religious significance. Hagiographies have also helped to maintain information about regional history and customs.

Writing in the early 20th century, the Jesuit Fr. Hippolyte Delehaye pointed out that the “hagiography” term “should not be applied indiscriminately to every document bearing upon the saints.” He added that a hagiography should be “inspired by devotion to the saints and intended to promote” such devotion.

Although often linked with the Church, hagiography is by no means the sole preserve of Roman Catholicism. It also has played a huge role in the Eastern Orthodox Church and Oriental Orthodox Church.

Additionally, the Jewish faith has its own rich tradition of hagiography. In modern times, this genre has been especially relevant among followers of the Hasidic movement who often use hagiography to celebrate the memory of prominent rabbis.

Hagiographic writings are also an important part of Buddhism, Hinduism, Islam, Sikhism and other faiths.

Christian hagiographies emerged as a distinct genre in the era of Roman persecution, when martyrdom was abundant and the circumstances bestial.

In the Middle Ages, hagiography was used as a way to enlighten the masses, most of whom were illiterate. During this era, Britain and Ireland were especially active with hagiography. Much of such writing appeared in Latin, but a significant portion appeared in the vernacular.

Organized scholarship of Christian hagiography began in the 17th century, and soon came under the domain of the Bollandist Society, which sought to apply a “firmer basis and a more rigorous application of the principles of historical criticism.”

To this day, the Bollandist Society, now consisting of both Jesuits and lay experts, continues research and scholarly assessment of Christian hagiographies.

And, since 1990, The Hagiography Society has promoted communication among relevant scholars worldwide.

This genre can pose quite the dilemma for scholars of faith: If they uncritically accept every idealized account, then they risk being viewed as ahistorical and unscholarly. At the same time, if they are too skeptical, then they risk being viewed as lacking in religious conviction.

In a secular setting, the terms “hagiography” or “hagiographic” are typically used as a put-down to describe writing with an excessively flattering view of the subject matter. This pejorative use of the word likely surfaces most often in the context of book reviews, with a reviewer contending that the book’s author has made an inferior effort to treat the subject matter with any objectivity.

Arguably worse yet would be the label of “autohagiography.” This would imply that the author seeks to give hagiographic treatment to himself.

Many would likely agree that self-hagiography is a peculiarly vain and unholy endeavor — one that should forever disqualify you from hagiographic consideration.