Lenten Campaign 2025

This content is free of charge, as are all our articles.

Support us with a donation that is tax-deductible and enable us to continue to reach millions of readers.

It seems absurd to say that a man who died nearly 1,600 years ago in a city that today lies in ruins remains relevant to our contemporary world, yet it’s true. Two selections from Aleteia’s 2023 Summer Book List show us why St. Augustine will always be modern. One of them is a moving historical novel, the other a delightful intellectual autobiography.

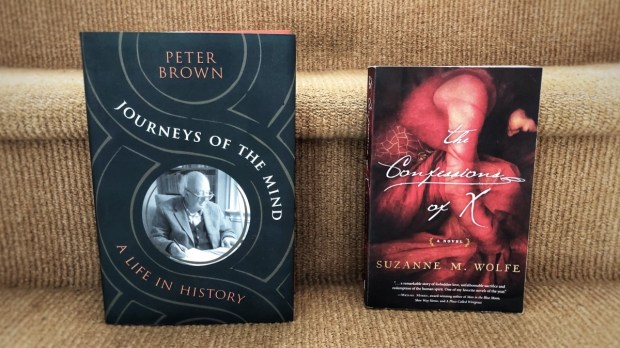

Journeys of the Mind

Journeys of the Mind: A Life in History by Peter Brown, Princeton University Press, 2023

Princeton University professor Peter Brown is one of the preeminent historians of our time. He pioneered the field of Late Antiquity studies, an undertaking that he recounts in his autobiography, Journeys of the Mind. Prior to Brown’s research, many scholars thought of the 3rd – 8th centuries A.D. as a period of ruinous decline. In their view, Rome fell, and a long and disastrous Dark Ages ensued.

The general consensus was that nothing much of interest had happened during that time.

Peter Brown showed that, to the contrary, the period that he relabeled Late Antiquity was a time of lively transition. Inspired by the relatively new Christian religion and various other influences, new ideas and cultural forms had begun to be explored and take root. It was also a period of impressive intellectual achievement, epitomized by the works of St. Augustine.

Keeping close to Augustine

Augustine of Hippo was Brown’s first book. It is still considered to be the finest biography of the saint ever written. Many chapters of Journeys of the Mind are devoted to the years when Brown undertook the formidable task of writing about a man who penned more than a million and a half words in his lifetime. It helped that Brown felt a natural affinity for Augustine. As he states in Journeys of the Mind,

What struck me most about Augustine was the care that he took to make his ideas intelligible to his readers. Here was someone who had grappled, throughout his life, to express himself – to drag his thoughts into the open, ‘through the narrow lane of speech.’ Augustine once wrote in 399 (when he was at the height of his powers as an author) to console a deacon who was anxious about his catechism classes. The young man should not worry: ‘For my own way of expressing myself almost always disappoints me… I am saddened that my tongue cannot live up to my heart.’ I found that, as a young author, I could identify my own ache to communicate with Augustine’s constant awareness of the hiatus between himself and the outside world. I knew instinctively that I myself would grow as a communicator (as well as in many other ways) by keeping close to such a person.

The adventure of a scholarly life

In Journeys of the Mind, Peter Brown convincingly portrays a scholarly life as something adventurous and romantic. The book is proof that the humanities still have a vital role to play in our time. It is also surprisingly fun, and a potent reminder that, even if the work can sometimes be lonely, good scholarship is never really a solitary endeavor. Just as in St. Augustine’s experience, it is the fruit of human relationships, of discussion, of debate, and — most importantly — of friendship.

The Confessions of X

The Confessions of X by Suzanne Wolfe, TNZ Fiction, 2016

Suzanne Wolfe is another writer haunted by St. Augustine, and even more so by the unnamed woman who bore him a son. Augustine’s concubine has been “lost to history,” as Wolfe explained in an interview with Aleteia.

As nothing is known of her—not even her name—my only way to do this was to research Augustine and his works and build up a picture of him. The blank space in the picture was the concubine.

The Confessions of X brings this woman alive for us. Though she remains nameless in the novel, we experience her pangs of longing for Augustine, her joy in her little son, and the agony she experiences when she is parted from both of them.

St. Augustine mentions the relationship in his Confessions. “It was a sweet thing to be loved, and more sweet still when I was able to enjoy the body of a woman,” he writes. At the time, Roman law strictly regulated marriage and it is likely that, as in Wolfe’s novel, class differences made it impossible for Augustine to take the woman as his wife. Concubinage was considered to be a socially acceptable way to live a monogamous relationship under these restrictions.

Humanizing what seems perplexing

Being ambitious, however, Augustine reluctantly agreed to break off the relationship fifteen years on. His mother, Monica, convinced him that for the good of his career, he should contract a legal marriage with a young heiress. All these centuries later, those events may sound perplexing and somewhat unsavory to us, but Wolfe does a wonderful job of humanizing the characters’ actions and making them understandable — though they sometimes remain frustrating.

A skillful novelist, Wolfe also brings the world of Late Antiquity to vivid life. She makes you feel the oppressive heat of Carthage on a late summer afternoon and how terrifying it must have been to flee in distressed confusion while an army of Vandals closed in.

Of course, in the end, Augustine did not marry the heiress. Instead, at the age of 31 his heart was conquered by Christ. We know the rest of the story well because St. Augustine gave us a blow-by-blow account of his soul’s struggles. Still, by the time you reach the harrowing, holy conclusion of Confessions of X, you realize how much of the story he had to leave out. Every human life is so full and beautiful, so complex and mysterious, that it cannot possibly be contained in any book, not even one as magnificent as St. Augustine’s Confessions.