Several years ago, I encountered the poems of Vittoria Colonna. Colonna was a rare creature, a Renaissance-era woman who became involved in the high arts. She was friends with many visual artists of the day, including Michelangelo, and was highly respected for her talent. I became so excited about what I read that I couldn’t wait to introduce Aleteia readers to her life and work.

The only issue with Colonna’s poems was that finding good English translations was difficult. In conversation with Anna Key, a Catholic poet whose work I greatly respect and who is essentially turning her entire life into a fascinating, living poem, I mentioned how interested I’d become in Colonna. Anna listened to me ramble on and on (and on) in the patient way she has. After our conversation, she disappeared back onto her sailboat located somewhere off the coast of Florida. Radio silence commenced. Months later, a manuscript of no fewer than 100 English recompositions of Colonna’s poems appeared in my inbox.

It was like someone had dug up a buried treasure and left it on my front porch.

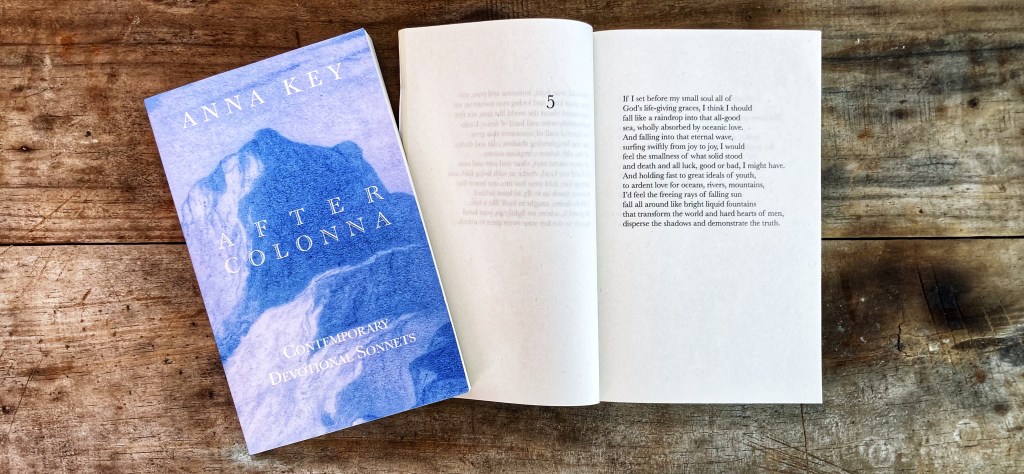

Those poems subsequently became a little book I cannot recommend enough, called After Colonna. It appears on Aleteia’s 2023 Summer Book List.

After Colonna is a gift of beauty to the world. One of my central beliefs is that all of us — no matter who we are or what our station in life is — are meant to contribute beauty to the world by making our lives beautiful. Beauty lifts our eyes to heaven and reveals the truth about God and the human soul. Poetry, music, and the visual arts are specific ways of being attentive to beauty, but really, it’s the whole of our lives that are poetic. This means that everyone is something of a poet. Even our smallest actions are connected to transcendent beauty.

For this reason, I thought it might be interesting to talk with Anna about poetry, both in written form and in the form of living a beautiful life. Here is our conversation.

I’ve already mentioned (shamelessly taken credit) for introducing you to Colonna, but what was it about her work that grabbed your attention?

You did introduce me to Colonna, thank you! I trust in God’s providence in every little movement of life, down to what appears to us the least significant details. It turns out that your discovery of Colonna and kindness in sharing your love for her poetry led me into the heart of the work I’ve been called to do on this earth. Without you, without Colonna, that would not have been possible. I love the way God interweaves our stories, how we can change people’s lives without even realizing it.

True art not only can change us but demands that we change in response to it. Colonna’s poems were a turning point in my life, one of those points where I could say, this was my life before Colonna, and this is my life after. The moment I opened the bilingual edition of the Sonnets for Michelangelo, I was hooked. Colonna’s vision is deep and wide, like the ocean, a thing you could never get to the bottom of.

I’d been thinking about and studying the sonnet form for ages. In graduate school, I had the good fortune to hear Terrance Hayes read from his wonderful book of poems called American Sonnets for My Past and Future Assassin. His sonnets are formally loose and poetically rich, alive with music, freshness of spirit, vitally new. I realized that the sonnet might be alive and well after all, but I was wrestling with the question of whether or not I could write my way toward a sequence of contemporary religious sonnets, which seemed to me at the time all but impossible.

I had written a chapbook of sonnet-esque poems called Leaf-Scraps; the poems in that collection were shaped like sonnets, but they weren’t formally sonnets and made no use of end rhyme. Neither were they explicitly religious. The disintegrating sonnet “Heliotrope,” in my first full-length collection of poetry, Notebook of Forgetting, is the closest I came to a workable form for a contemporary religious sonnet. But it only worked because I let it disintegrate — held together, it was heavy. It accumulated weight. Then came Colonna: she acted like a springboard, helping me to leap into the form I had been seeking.

At first, I thought that you’d written translations of her sonnets from the original Italian. It turns out that what you actually created is more subtle. At least initially, you called these sonnets “recompositions.” What does this mean?

I was reading Colonna’s Sonnets for Michelangelo, immediately taken with the passion and clarity of her vision, but also put off — as I always am — by the lack of poeticity in translations that try to stay very true to the original, especially when that original is from a long time ago. Staying true to the original is of course a goal of every translator, and there’s a place in the world for such translations: they help us see into the specifics of life in another time and place. But I’m a poet, and I want the poetry more than the history or the accuracy.

We need scholars to preserve these things so that future translators have faithful versions to help guide them in their efforts; but I’m always looking for a poem that can speak to me now, in this time and place. I think there’s some truth to Frost’s famous quip that poetry is what goes missing in translation; and also, to the observation of the Japanese poet character in Jim Jarmusch’s film Paterson, who says, “Reading poetry in translation is like taking a shower with raincoat on.”

I began to ask myself how I could reach into Colonna’s poems, find the spirit that gave rise to them, make it present and visible today, in English. Thinking of the living poems-in-translation of poet-translators like W.S. Merwin and Robert Bly, I started by asking myself if I could translate Colonna as effectively. I had attended a weekly Dante reading group in college for years with a professor who required us to begin by reading aloud and discussing the Italian first. That gave me enough exposure to the language to plod my way through with a dictionary, a grammar, and Brundin’s translations — but also enough distance to give myself space to search out fresh forms of expression.

Problems began to emerge from the start: Colonna’s language and culture are very far from our own, and she says things in ways our ears simply can’t hear. The first sonnet is the closest I came to something like a translation. It stays very close to the original images and ideas but takes enough liberties that I realized early on I’d be uncomfortable calling these “translations.” I began to search out different ways to envision what I was doing. I thought of the lovely piece of music called Recomposed by Max Richter: Vivaldi’s Four Seasons and wondered if I might not take his idea of recomposition and apply it to Colonna: re-compose the poems, re-imagine them, make them new.

As I began to send some of the sonnets out into the world, I was still thinking of them as recompositions. Several of the poems were published individually under the title, “Vittoria Colonna’s Sonnets for Michelangelo, Recomposed by Anna Key.” But as I spent more time with them, and had occasions to hear people discussing them in conversation and in print, it became clear that the recomposition idea was creating ambiguity as to who had written them: were they Colonna’s sonnets, or mine? I’d see quotes from the poems show up in print that were ascribed to Colonna, from sonnets in my sequence that diverged so completely from Colonna’s originals that it seemed somehow wrong to put my words in her mouth, as it were. I became uncomfortable with ascribing things to her that she manifestly didn’t say. I neither wanted to understate nor overstate the degree to which her poems made mine possible.

In the end, I decided to abandon the idea of recomposition and to call the collection After Colonna, because even the poems that stayed close to Colonna’s sonnets became something different. Some of my poems have almost no discernible points of contact with Colonna’s. There are often anachronistic references to more contemporary poems and figures (Eliot, Dickinson, etc.) and even some poems that refer directly back to Colonna, addressing rather than translating or recomposing her. I wasn’t systematic in staying faithful to the specific content of her poems, only determined in my efforts to remain true to the spiritual journey they contain.

On a practical note, I decided to retain the rhyme scheme of the original sonnets (Petrarchan: abba abba cde cde and its variations), but I allowed myself play in the meter (it’s not regular) and in the line length: the decasyllabic line formed a base from which I deviated a bit, running between nine and 12 syllables (rarely more) as the writing demanded. Of course, retaining the rhyme scheme had the effect of often pushing me farther and farther away from the content and images of the originals—but this proved a blessing, as though Colonna were reaching down and untying the dock lines, saying, “Go, go where you need to go, find your own way.” She really did set me free, while remaining with me in all the ways that matter.

Every writer has a unique style of writing, what we might call her voice. The way we communicate arises from somewhere deep within ourselves and carries with it a specific perspective. Everyone sees the world through their own eyes. With Colonna’s poetry, was it difficult to capture her voice?

Insofar as I had abandoned early on the idea of translating the poems, the real difficulty I faced wasn’t capturing her voice but finding my own. Even as I was thinking about the sonnets as “recompositions,” the point was to re-write the sonnets, to write them in a fresh, contemporary idiom, in a contemporary voice. What I found compelling about Colonna’s voice was the boldness and directness of her faith and her forms of expression. Her faith runs deeper than mine, and she has a wider range. So I wanted to bind myself to her, to follow her lead and allow her to guide me into that deeper faith, to help me find the bold, direct, clear forms of expression I had been seeking for so long but was still unable to reach. Her words gave me the courage to find my own.

A perfect example of the way this worked in the composition process is Sonnet 97, where Colonna says something like “my faith is like a rock.” It’s a strong poem, warrior-like, humble in that it boasts only in Christ, as St. Paul says, and I admired it deeply; but it has a confidence that I lack and could not adopt without artifice. So I started there, with the admission that my faith didn’t feel like that, and wrote the first line: “I cannot now say: my faith is like a rock”—and then, somehow, a different vision began to emerge, one that pulsed with the life-force of Colonna’s sea images but took a different tack; and the resulting poem, at once bound to Colonna’s images but so very different in its directionality, felt true, where it could not have been had I tried to speak as Colonna speaks, to say what she said.

Part two of our interview with Anna Key will appear in Wednesday’s edition of Aleteia.