Lenten Campaign 2025

This content is free of charge, as are all our articles.

Support us with a donation that is tax-deductible and enable us to continue to reach millions of readers.

Japanese society remained in a state of psychic shock in the early 1950s. Prior to World War II, military conflict had been seen as a glorious endeavor. The bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki made it clear that war was actually a horror that could literally unleash the Apocalypse. Even though Japan was modernizing following the Occupation and Reconstruction, the sense of impending doom lingered.

This trauma is expressed with spellbinding clarity in Japanese kaiju movies. When Gojira (better known to us as Godzilla) appeared in 1954, audiences flocked to theaters and a new film genre was born. There followed a whole spate of movies about giant monsters attacking humanity. They reflected Japan’s – and the world’s — nuclear nightmares and the persistent sense that on any given day the forces of chaos might be unleashed.

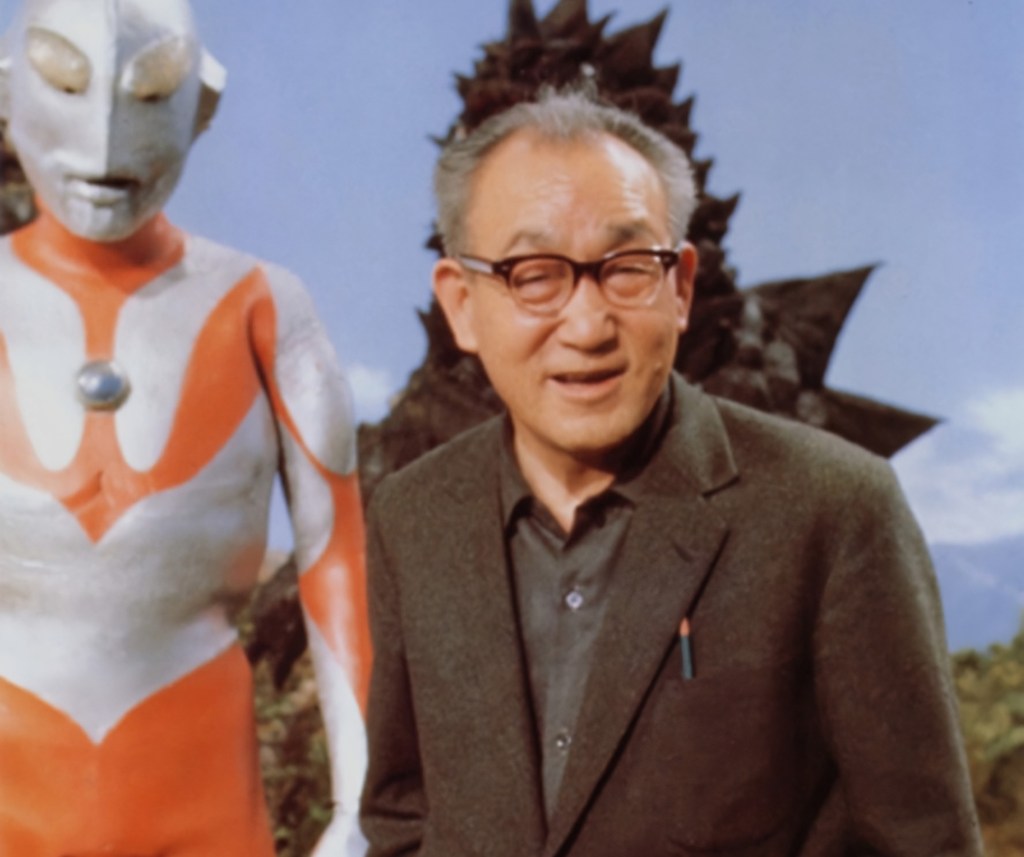

Eiji Tsuburaya, maestro of magic

Eiji Tsuburaya (1901-1970) was one of the pioneers of the kaiju genre. A special effects whiz, he invented new ways to film men in monster suits and make them look cinematically compelling. The results are in no way realistic the way CGI effects strike us today. Yet the “suitmation” effects Eiji Tsuburaya created for his monster epics are no less spectacular and, in my opinion, much more magical.

Though raised in a Buddhist family, Tsuburaya’s wife was Catholic, and he would eventually become a convert. By all accounts, he was a devout believer. His faith is clear in his film and TV work, though you may not immediately recognize the Christian references amid all the miniature cityscapes and rubber monster suits.

Nowhere is Tsuburaya’s Catholicism more evident than in his TV series Ultraman.

Spaceships collide and a savior is born

The premise of the show is delightfully wacky and innocent. Hyata, a space pilot working for the Scientific Investigation Agency, is on a reconnaissance mission when his ship collides with a glowing, anomalous object – a UAP in today’s lingo. The object is really an alien spacecraft from Nebula M78. Hyata is killed in the crash, but the alien pilot gives his life to save Hyata. Human and alien are joined. Going forward, whenever Japan is threatened by a rampaging monster, Hyata will activate his Beta Capsule and transform into the 40-meter-tall hero known as Ultraman.

While Ultraman remains a huge cultural phenomenon in Japan, it never really enjoyed the same “monstrous” popularity elsewhere. I fondly remember watching the series as a child, however. To say I was obsessed with the show would be an understatement. There remains something oddly therapeutic about watching colossal monsters smashing our civilization into ruins, especially when you know Ultraman will eventually fly to the rescue.

Malevolent forces prey on humanity

The monsters Ultraman faces are not just expressions of destructive rage, something the 10-year-old me found easy to relate to. Baltans, Giant Ragons, and Antlars (yes, those are all real Utraman villains) also represent all those malevolent forces that constantly prey on our fears — war, the threat of nuclear Armageddon, pandemics, and unnamed disasters both natural and unnatural. Like kaiju monsters, these forces seem far too enormous for us puny humans to deal with. Sooner or later death and destruction must inevitably win out.

A voice within tells us that if we are going to avoid annihilation, we will need a miracle. We yearn for a savior to appear and say to us what the alien says to Hyata moments before they are joined: “There is nothing to fear.”

Christian imagery with a kaiju twist

As in some of this other kaiju projects, Eliji Tsuburaya peppers his show with Christian imagery. It’s quite clear that Hyata/Utraman is meant to be a Christ-like figure who is willing to sacrifice himself for the salvation of others. The metaphor is made explicit when a demonic monster asks Ultraman if he is an alien or a human. “I am both,” Ultraman replies.

And when Ultraman defeats his foes, he makes a cross with his arms and shoots out a beam that obliterates the evil monster-of-the-week. I’m reasonably sure that Jesus never did anything like that in the Gospels, but since this is a fantasy series, we can appreciate the moment for its symbolic value: the cross as a symbol of the victory of love and goodness over evil and destruction.

My wish is only to make life happier and more beautiful…

David A. King, a professor of English and Film Studies, penned an interesting essay for The Georgia Bulletin in which he said of Tsuburaya:

In many ways, the attempt to recover both his sense of childhood innocence and his Catholic sense of meaning represents the guiding principle of his life and work. As Tsuburaya said a few years before his death, “My heart and mind are as they were when I was a child. Then I loved to play with toys and to read stories of magic. I still do. My wish is only to make life happier and more beautiful for those who will go and see my films of fantasy.”

This brings to mind the passage in Orthodoxy when Chesterton says that “the things I believe in most now are the things called fairy tales. They seem to me to be the entirely reasonable things … I knew the magic beanstalk before I had tasted beans; I was sure of the Man on the Moon before I was certain of the Moon.”

Battling giant monsters = walking on water?

That sense of wonder is something the characters in Utraman feel strongly. In innumerable episodes there are shots of onlookers with mouths agape, staring in awe as Utraman thwarts yet another nightmarish creature. The Apostles probably wore similar expressions as they watched Jesus walking upon a stormy lake or raising Lazarus from his tomb.

Of course, the parallels between the Gospels and a kaiju series only go so far. Ultraman isn’t meant to be a work of Christian apologetics, but an entertaining kids’ show. We never see Hiyata or Utraman being baptized or reciting the Nicene Creed. Still, I feel very confident in asserting that Utraman is indeed Catholic in the same way that The Lord of the Rings is Catholic and The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe is Christian.

Lewis, Tolkien, and Tsuburaya

Like Tolkien’s Middle Earth or Lewis’ Narnia, the world that Tsuburaya created in Utraman is a fantastic, larger-than-life sub-creation that is nonetheless reflective of the Christian understanding of reality. It expresses, in mythological (and very playful) terms a truth that humankind only became aware of with the coming of Christ.

Yes, the world can be a dark and dangerous place, but there is always hope because we have an ultra-incredible Friend who loves us and has sacrificed himself to save us.