Lenten Campaign 2025

This content is free of charge, as are all our articles.

Support us with a donation that is tax-deductible and enable us to continue to reach millions of readers.

A priest and a church musician have teamed up to produce a tragic opera concerning civic unrest during the Roman Republic and the lives sacrificed to bring about peace in the Eternal City.

The opera, Gracchus, will have its world premiere in Connecticut this weekend, with a cast of nine soloists, a chorus and orchestra, as well as ballet scenes interspersed throughout the two acts, helping to tell the tragic story.

One climactic moment might remind theater-goers of a much-discussed event in recent American history: the January 6, 2021, mob uprising in Washington, D.C., related to charges against former President Donald Trump of working to overturn the results of the 2020 election. But any similarity between the historical incident in the opera and the attempt to stop the certification of the election of President Biden is purely coincidental.

“Just when the tragic hero – Gaius Gracchus – just before he crashes and burns, he attempts to lead the Roman mob to the Senate, and the oligarchs are inside,” said Fr. Richard Munkelt, the opera’s librettist. “He bangs on the doors and demands a reform, with the mob in tow to back him up. It’s a bizarre January 6th parallel, but I wrote the scene years before Donald Trump was president.”

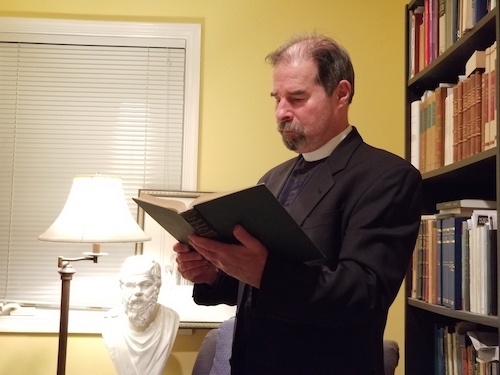

Indeed, the opera has been in the making for a long time, including seven years to set the work to music by composer David Hughes. Fr. Munkelt, a diocesan priest in residence at the Oratory of St. Anthony of Padua in West Orange, New Jersey, has had a lifelong interest in the classics, at least since his undergraduate days at Kenyon College in Ohio. The Connecticut native holds a doctorate in philosophy from the University of St. Thomas Aquinas in Rome and exclusively celebrates Mass in the Extraordinary Form at the oratory, which is run by the Institute of Christ the King Sovereign Priest.

A chance meeting

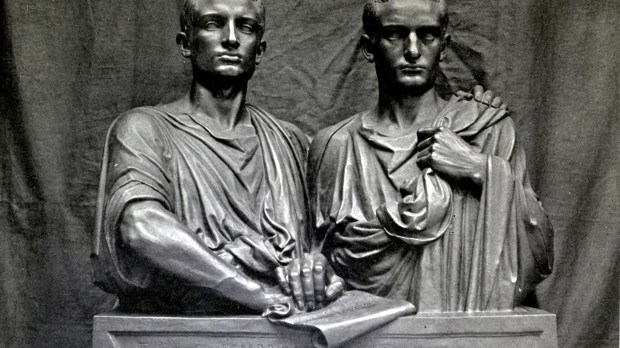

Fr. Munkelt came upon the story of Tiberius and Gaius Gracchus, brothers who were tribunes in the Roman Republic, working to protect and advance the interests of commoners. Their lives and the times in which they lived were so full of drama that Fr. Munkelt felt it was all ripe for operatic treatment.

The action takes place in 121 B.C. The Roman Republic, which had existed for almost 400 years, was breaking down in terms of political coherence. “Things were falling apart,” the priest-librettist said in an interview. “The Republic sort of turned into an oligarchy of a number of very wealthy patricians, or aristocrats, and they had a political party or faction, very wealthy aristocrats called the Optimates. The Optimates were trying to prevent the reform of the system, and the two brothers, Tiberius and Gaius, attempted to institute judicial reform and — more importantly — agrarian reform, because all the farmland had fallen into the hands of an oligarchical regime of the most wealthy families and had dispossessed many Roman veterans and farmers who were the backbone of the Roman Legion.”

Rome was starting to fill up with destitute and dispossessed veterans and farmers, undermining the civil order, the priest explained.

What’s interesting, too, is that the Gracchi brothers, though grandsons of the great Roman military leader Scipio Africanus, also had Plebeian blood.

Fr. Munkelt is quick to point out that he fictionalized a good deal of the character of Gauis Gracchus, including a ghostly visit he receives from his assassinated older brother. Munkelt also developed a subplot concerning mercy, conversion, and sacrifice. Gaius begins as a drunken ne’er-do-well who neglects his wife, Licinia, who in turn is seduced by a political rival. She is repentant, however, and he mercifully spares her life. The couple’s reconciliation is a high point of the opera.

“This reconciliation is so important that Gaius cannot go on and do the political work that is at the family legacy until he takes care of that first,” Hughes said.

But Gaius’ unwavering sense of duty in the political realm, in spite of his wife’s pleas to pull back from his activism, leads to his demise.

Universal themes

Fr. Munkelt originally conceived of the story as a play, but soon began thinking in terms of opera. He needed to find someone with the requisite musical skill and talent, however.

Mutual friends invited him and David Hughes to a dinner party and, as Hughes relates, “Somehow towards the end of the dinner the subject of opera libretti came up. Fr. Munkelt said, ‘Well, I’ve got an opera libretto,’ and I said, ‘Yeah, okay,’ and he said, ‘No, I seriously do.’ And he started to tell me this story.”

Hughes found the tale to be “one that would lend itself very, very well to the operatic stage.”

It turns out that Hughes also works for the Institute of Christ the King, a relatively new religious order that is devoted to celebration of Mass in the Extraordinary Form. He is organist and choirmaster at their oratory in Waterbury, Connecticut, St. Patrick’s. Having composed much choral liturgical music, he felt he knew enough about the capabilities of the human voice to take a crack at opera.

Munkelt considers Hughes to be “a creative musician, and his technical composition is brilliant. And more importantly, his music is just inspirational, soaring and unique.”

Hughes characterized his style by saying that the “harmonic language and the texture is relatively something contemporary.” But the opera follows a classical structure, as it maintains a distinction between aria and recitative.

Taking a break from a dress rehearsal last weekend, Hughes commented that it felt “great to have these characters whom I’ve lived with in my musical imagination for so long, to see them step forward on the stage. It’s like being reunited with old friends.”

Both men consider the deeper themes of the opera to be what’s most important – themes that, they believe, are related to universal human values.

“There are allegories to be drawn between that period and our own situation in the world right now, where there’s such a divide between the haves and the have-nots and one that’s growing all the more,” Hughes said. “But part of what this opera is looking at is the philosophical underpinnings of that and then how that translates into sort of practical politics, so to say.”

“What we wanted to do was get back to big opera with classical themes, themes that transcend time and place, themes about love, about the universe, about man’s destiny, and the human condition,” Fr. Munkelt said.

Added the priest-librettist: “Even though the story takes place in the late Roman Republic, at the end of the day it’s not about the Roman Republic; it’s about the human condition, the universal values and truths about human nature and man’s destiny and the nature of the universe.”