Throughout his adult life, Bishop Macram Max Gassis remembered something that happened in his childhood home in Khartoum, the capital of Sudan. A man from South Sudan – Black and quite different from the mostly Arabic residents of the capital – collapsed in the ditch in front of his parents’ house. His mother, who came from a Coptic Orthodox background, and his Catholic father carried the man into their home, put him in bed and cared for him until he recovered the next day.

“The parable of the Good Samaritan in action!” wrote John Ashworth, in a 2022 article about Macram Gassis, who would go on to serve the people of the southern part of the country, particularly the Nuba people, as a priest and bishop. Though a difficult political situation for many years prevented him from being with his flock, he took their plight to the world stage, advocating for victims of an Islamist regime in Khartoum.

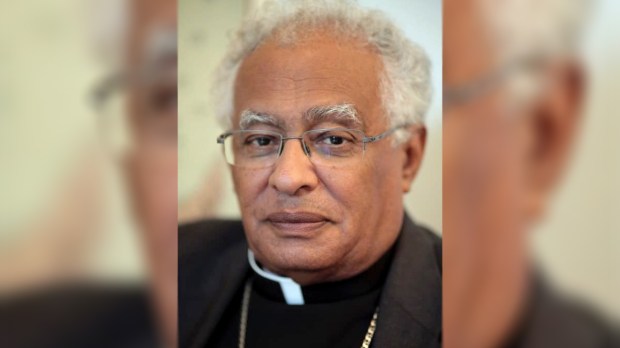

Bishop Gassis died June 4 at the age of 84. He had been staying with relatives in Pennsylvania and had been unwell for some time. On Tuesday, June 13, Bishop Ronald W. Gainer of Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, will offer a funeral Mass for the late bishop.

But already, a day after Bishop Gassis’s death, a Mass was offered at the Catholic parish in Gidel, in the Nuba Mountains of Sudan, where he had founded a hospital to serve the Nuba people. There was “quite a large crowd attending,” reported Dr. Tom Catena, medical director of Mother of Mercy Hospital. Their presence was a sign of the love and affection his people had for Bishop Gassis.

But in another sign of the times, Bishop Yunan Tombe Trille Kuku Andali of El Obeid, Bishop Gassis’s successor, was unable to attend the Mass, because of the war that broke out in Sudan in April. Sadly, a peace for which Bishop Gassis worked for years has been shattered once more.

“Outspoken defender”

Dr. Catena, who for many years was the only doctor serving a vast area of the Nuba Mountains, called Bishop Gassis “an outspoken defender of Christians and the marginalized of Sudan.”

“And he paid for it by having to leave Sudan in the early 90s and live in exile in Kenya,” said Catena, a New York native.

It was largely through Bishop Gassis’ efforts that the Church is what it is today, he said.

“Although St. Daniel Comboni established the Church in Sudan over 140 years ago, it was Bishop Macram who brought the Church to this part of the Nuba Mountains,” Dr. Catena wrote in an email. “In addition to setting up three parishes during the previous civil war, he built this hospital, several schools and dug boreholes [for well water]. Any development in this part of Nuba was started by the Church, and Bishop Macram was the catalyst behind it.”

The bishop’s tireless work had an effect both inside Sudan and internationally. Gabriel Meyer, who went to Sudan with Bishop Gassis several times and wrote the 2001 film The Hidden Gift: War and Faith in Sudan, said that the bishop was instrumental in bringing to fruition a no-fly zone over the Nuba Mountains during a decades-long civil war between the North and the South; in compelling ceasefire talks, and in opening the region to relief organizations and journalists.

In addition, he strengthened the Nuba people’s sense of dignity so that they could better resist the North’s efforts at Islamizing the South.

“What Gassis did when he would fly in on these quote-unquote illegal flights to the Nuba Mountains was that he wasn’t just bringing a missionary infrastructure – which he was, in priests and sisters and so forth – but he was bringing civilization, because what he was enabling this war-torn population to have, even in the midst of the war — they had schools and they had parishes and they had medical clinics,” Meyer said in an interview. “I often used to say that Gassis enabled the Nuba people to resist because he in effect built stations of civilization even in the midst of the war, which allowed the people to have something of a semblance of a normal life and really enable that and to deal with some of the issues that they’d been dealing with.”

Nobel Peace Prize nominee

Meyer, who wrote the 2012 application nominating Bishop Gassis for the Nobel Peace Prize, on behalf of the Bishop Gassis Sudan Relief Organization, added that the bishop was a “real champion” of Catholic-Muslim cooperation. There was already a culture of mutual tolerance and interreligious cooperation in traditional Nuba culture, he pointed out.

“But Gassis really went into the trenches with that and met with Muslim leaders, and it enabled Muslims then to join with their Catholic neighbors in resistance to a northern Sudanese regime which claimed to act in the name of Islam,” said Meyer, a longtime journalist. “So that was a really big thing, that you had Nuba Muslims refusing Khartoum’s project to bring Sharia law to the Nuba Mountains because of this natural culture of tolerance which has been built up over centuries, of course, but also Gassis’s particular work to enable Muslim leaders to see that their interests were with Catholics, that they had mutual interests, and that Khartoum was against both of their interests. So it was a very significant contribution during the war and afterwards as well.”

It helped, said Meyer, that Bishop Gassis was himself a Northerner, who had “gone to school with Khartoum’s elite – many of whom were running the government that was persecuting his people. For Gassis, a distinguished member of the Khartoum elite, to identify with the Nuba and the Dinka of the South, and in such a profound way as he did, is unique.”

Feared and persecuted

It’s also why Khartoum, particularly under Omar Hassan Ahmad Al Bashir, who was head of state of Sudan from 1989 to 2019, feared him and tried to control him.

“The government feared him more than they would a southerner, as he was Arab through and through; he knew them, could think like them, speak their language perfectly and could often out-maneuver them,” wrote John Ashworth, a fellow of the Rift Valley Institute in Nairobi, Kenya, in a 2022 article in The Journal of Social Encounters. “His life was threatened and thus he had to flee into exile.”

Born in Khartoum in 1938, Macram Max Gassis attended primary and secondary schools run by the Comboni Missionaries of the Heart of Jesus. He felt called to the priesthood in this order, founded by the Italian St. Daniel Comboni, and did his seminary education in England and Italy from 1955 to 1964. In 1964, he was ordained a priest in Verona, Italy.

Fr. Gassis returned to his home Archdiocese of Khartoum and served as an assistant parish priest in central Sudan. In 1965, he established parishes in Eastern Sudan, and in 1971 was appointed chancellor of the archdiocese.

From 1973 to 1983, Fr. Gassis was Secretary General of the Sudanese Catholic Bishops’ Conference, during which time he earned a degree in canon law and administration from The Catholic University of America in Washington.

In 1983, he was appointed Apostolic Administrator of the Diocese of El Obeid in central Sudan, and for two years was chairman of Caritas Sudan. The diocese comprises an area of more than 340,000 square miles, including the Darfur region.

In 1988, he was consecrated bishop of the Diocese of El Obeid. As the only Arabic-speaking member of the Bishops’ Conference, Bishop Gassis served as the liaison between the Sudanese government and the Bishops’ Conference.

However, the government brought a criminal indictment against him a year after his 1988 testimony before the U.S. Congress. His testimony complained about human rights abuses, including enslavement of innocent civilians, air raids, forced starvation, and rape at the hands of the army.

Receiving treatment for pancreatic cancer at Georgetown University Hospital in 1990, he was advised not to return home for security reasons. He overcame his cancer, and for four consecutive years, from 1992 to 1995, he brought his concerns about Sudan before the United Nations Human Rights Commission in Geneva.

“He became a globe-trotter, giving conferences on human rights, the persecution of Christians and of the African race, slavery, the rape and forced concubinage of Nuba and Dinka women and girls, the killing of the elderly, and the use of food to Islamize and Arabize the non-Arab peoples of Sudan, by the Khartoum regime,” Ashworth wrote.

Bishop Gassis’s adopted Nuba Mountains region was a major target for Khartoum’s forces, Ashworth noted, “partly because of oil and minerals in the region, partly because it was an area within northern Sudan which resisted Islamization and Arabization, and partly perhaps because of the more tolerant model of Islam which it embodied, a model which challenged the aggressive Islamist policies of the Khartoum regime.”

“Water is life”

Ashworth remembers flying with the bishop into the area from Kenya, where Bishop Gassis had a base-in-exile, on an “old DC-3” that had already made an emergency landing for engine failure. The dangerous flight was nothing compared to what awaited them.

“The bishop was shattered by the situation of the people in the Nuba Mountains,” Ashworth recalled. “No health facilities, no education, no clean water. One of his first concerns was water, a passion which is never far from his mind and heart: ‘Water is life; no water is death; brackish water is sickness.’ He found the people digging in dry river beds and scooping dirty water out with a calabash. He appealed to various organizations to provide assistance, but to no avail. Eventually he lobbied in the USA where, with the help of Congressman Frank Wolf and Senator Sam Brownback, he was able to get funding from USAID, channeled through Catholic Relief Services, for a mobile drilling rig. To date, the bishop has drilled more than 250 boreholes to provide clean water for the people.”

In addition, there was no hospital serving a population of several hundred thousand people, and those people were “completely trapped by the war and could not even travel to reach the few hospitals on the other side of the front line,” recalled Ashworth. This led to the founding of Mother of Mercy Hospital in Gidel, which was followed by the establishment of other hospitals in the region.

Even after his official retirement in 2013 at the age of 75, the Bishop Emeritus could not hang up his boots. Though there was a Comprehensive Peace Agreement in 2005, conflict had broken out in the Nuba Mountains, and Bishop Gassis went into areas where even the administration of the Diocese of El Obeid could not. And although South Sudan became independent in 2011, the new nation itself experienced a civil war, and, according to Ashworth, “again Macram found himself in demand to provide pastoral and humanitarian services to the suffering people.”

For his work and witness, Bishop Gassis was the recipient of many accolades, in addition to the 2012 Nobel nomination. In 2000, he was honored in Washington with the 12th annual William Wilberforce Award from the Prison Fellowship for his efforts to end religious persecution in Sudan. In 2001, the University of San Francisco presented him with an honorary doctorate in humane letters.

Bishop Gassis’ family is asking well-wishers to consider donating to the Comboni Missionaries in his name. And, as fighting continues in Sudan and its people continue to suffer hardship, no doubt there are many there who now are thinking of calling on Bishop Gassis for his intercession.