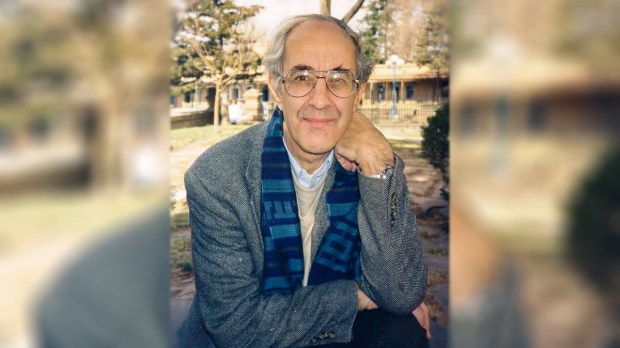

Besides being a well-known spiritual writer and speaker, Henri J.M. Nouwen was a diarist. The journal he kept during his seven months living with monks later became a book, Genesee Diary: Report from a Trappist Monastery. The time he spent at the first L’Arche community in Trosly-Breuil, France, likewise was documented in a personal journal, later becoming The Road to Daybreak: A Spiritual Journey.

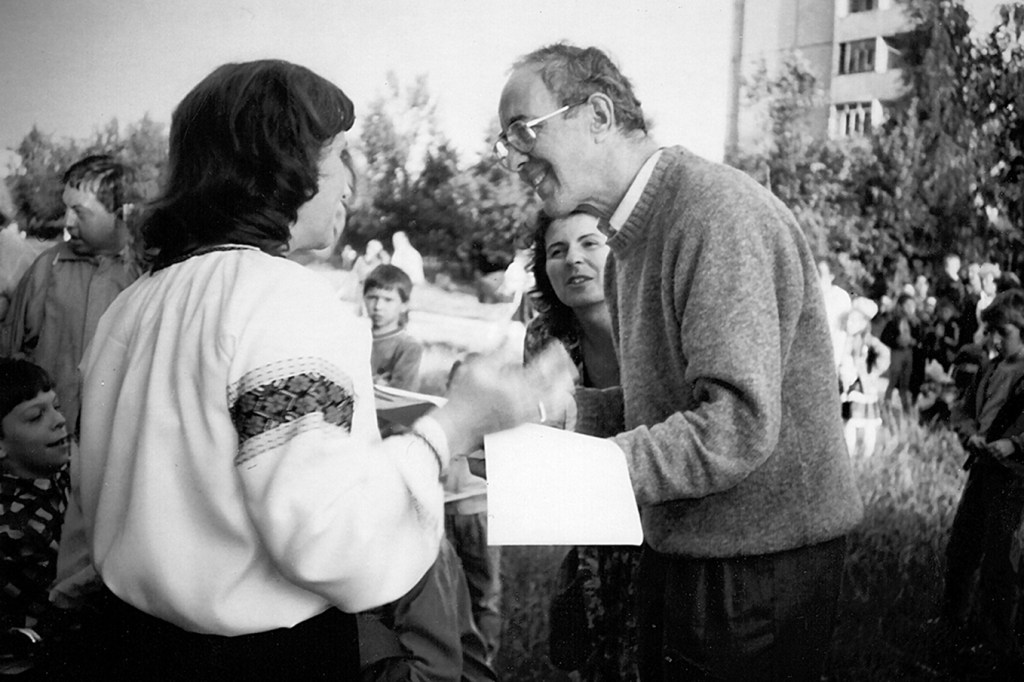

Now, 27 years after Nouwen’s death, Orbis Books has brought out an English edition of Ukraine Diary, a brief but illuminating chronicle of the Dutch priest’s summer visits to Ukraine in 1993 and 1994 to preach and to support the development of programs for the mentally disabled. The slim volume is a rich glimpse into the life of a country that had won its independence just a few years earlier. And, of course, the book sees the light of day at another important time for Ukraine.

Orbis’s publisher, Robert Ellsberg, writes in the preface that Nouwen had approached him after his first visit to Ukraine. But Ellsberg didn’t feel the short diary would interest enough people and advised him to take it to a periodical. The 1993 diary was published serially in the New Oxford Review.

Ellsberg was not aware that Nouwen returned to the Eastern European country the following year and intended to keep going back. It wasn’t until Nouwen’s sudden death from a heart attack in 1996 that his brother Laurent discovered the second diary.

Laurent Nouwen carried on his brother’s work for the disabled in Ukraine, and eventually, Nouwen’s two diaries were published in that country – just months before Russia’s February 24, 2022, invasion of Ukraine.

Two key people

Nouwen’s road to Ukraine is just as interesting as the time he spent there and the vision he had for care of the marginalized there. He had a prestigious job teaching at Harvard Divinity School, the pinnacle of a 20-year career in academia, but left to answer a call to work as a chaplain at the L’Arche Daybreak community in Toronto. Those two places where he exercised his ministry – the ivory tower and the humble world of those with mental illness – put him in touch with the two people who would eventually interest him in Ukraine. Both were children of Ukrainian emigres, and both took such a strong interest in Ukraine’s post-Soviet development that they moved to their ancestral homeland.

The first of these two key people in Nouwen’s life was Borys Gudziak, who was working on a doctorate in Slavic studies at Harvard when he befriended the Dutch spiritual writer. Gudziak would go on to become a priest in the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church, which had been suppressed by the Soviet Union for almost half a century. He was instrumental in founding the Ukrainian Catholic University in Lviv, where he served as rector for many years.

Now head of the Ukrainian Catholic Archeparchy of Philadelphia, Archbishop Gudziak has become a prominent voice in the United States for support of Ukraine since the 2022 invasion. He writes the introduction to Ukraine Diary and is mentioned many times in the diary itself.

The other person who invited Nouwen to Ukraine and who, along with Gudziak, served as his guide both summers is Zenia Kushpeta, a Canadian whom Nouwen had met at L’Arche Daybreak in Toronto. Ellsberg tells us that Kushpeta worked to “bring the spirit of L’Arche to her work with handicapped adults” in Ukraine.

As Archbishop Gudziak explains, he and Kushpeta were eager to share with Nouwen “our world, one traumatized by totalitarianism but one full of hope and determination to rebuild. I also wanted the Church in Ukraine and the future university team to be inspired by Henri’s insightful perspectives on living a life in Christ. Henri became directly involved in forming the vision of the university, which came to place ostracized persons with different mental abilities at the center of its identity. We needed the help and witness of the so-called ‘disabled’ to address the post-traumatic shock, i.e., the post-totalitarian disabilities of Ukrainians shared with some two billion people between Estonia and Albania and China and Vietnam that endured communist rule or continue to do so.”

The marginalized

Indeed, the Ukrainian Catholic University in Lviv still houses a good number of persons with disabilities, who are active in the life of the university. As Gudziak puts it, they “act as tutors of human relations, as teachers who … help us see God in each other. Our friends with different mental abilities do not care if one has high SAT scores, is rich or powerful, a winner in competitions, glamorous or famous. They care about and express one fundamental truth of the Gospel, asking with their presence and being Jesus’s most basic question: ‘Do you love me?’”

Some of the most interesting and valuable parts of Ukraine Diary are those in which Nouwen observes a Ukraine emerging from Soviet domination – and the vulnerability the country had at that time of being reabsorbed by that empire.

“With so many voices in Russia wanting to reclaim Ukraine as part of their territory, there is the constant fear that independence might be a very fragile thing,” he wrote on August 4, 1993. “The fact that the United States pays so much attention to Russia and so little to Ukraine, except in trying to have it give up its nuclear arsenal, makes Ukrainians question how much international support their independence will get when push comes to shove.”

His words, of course, have taken on a new meaning 30 years later. But it reminds us that Russian President Vladimir Putin’s ambitions and Ukraine’s vulnerability are nothing new.

In an entry from the following summer, Nouwen reflected on the “complicated Ukrainian history” that young Borys Gudziak was sharing with him and the others on the trip.

“What struck me most in reviewing this history was that independence is a new concept for Ukraine,” he wrote. “Except for the two years of failed independence in the post-World War I years, Ukraine has in modern times never experienced a clear national identity. Even today there are many discussions about the nature of the Ukrainian state. Is it a political, an ethnic, or a territorial unity? Is there enough basis on which to build a state? Many Russians consider present day Ukraine as a totally artificial entity. Is there enough inner cohesion to keep together a nation that has little experience of statehood and that includes a 25% minority population? Or is it doomed to be torn apart constantly by inner strife and outer aggression? At present there is a lot of anxiety around these questions.”

Nouwen saw Ukraine as a wounded, marginalized country in far-flung Eastern Europe. Within that wounded society he found that people with disabilities had for too long been neglected and largely forgotten.

“Our trips to Ukraine show us another type of handicap,” Nouwen reflected after returning home after his second trip. “It is the handicap that comes from a broken history, from centuries of oppression and exploitation, from neglect and indifference of the wealthy nations, from the social sins of injustice and greed.

“I know in a new way,” he concluded, “that the people we have met there challenge us to be faithful to our commitment to the poor and to trust that through that faithfulness we will find true joy and peace.”