“‘If you wish to be perfect, go, sell your possessions, and give the money to the poor, and you will have treasure in heaven; then come, follow me.’ When the young man heard this word, he went away grieving, for he had many possessions.” (Mt 19:21-22).

Everyone knows the story of this son of a good family attracted by Christ but unable to go through with renouncing the advantages of this world. He wrested from the Lord this sad comment:

“It is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle than for someone who is rich to enter the kingdom of God” (Mt 19:24).

At the beginning of the 1930s in Spain, a wealthy and worldly young man, seemingly destined to enjoy all the pleasures of life, decided to abandon everything to follow Jesus. Due to particular circumstances, he ended up answering that invitation to follow the Lord not once, but four times. His path ended on the cross.

Dreams of being an architect

“This boy is crazy.” This is what Brother Tescelino, a novice of the Trappist monastery of San Isidro de Duenas, told his relatives in the spring of 1938. The crazy boy he was talking about was his novitiate classmate, St. Rafael Arnáiz Barón.

We have to admit that to human eyes, his attitude is incomprehensible. After all, when everything seemed to lead him away from the austere Cistercian life, he clung to what he claimed to be his vocation. This, even though he found in the cloister only suffering, misery, rebuffs, and humiliations, when at home he could lead a pleasant existence without shame or remorse! Was he really crazy? No: but Arnáiz was the man in the Gospel parable who discovered a “pearl of great price” and decided to liquidate his entire fortune in order to buy it.

Rafael was born in Burgos (northern Spain) on April 9, 1911, into a very high society family. His father was a renowned jurist, an important landowner, and very rich; his mother belonged to the aristocracy. The four Arnáiz Barón children were therefore born with “a silver spoon in their mouths.” However, three of them would renounce all this in favor of consecrated life, and Rafael (the eldest) would set the example.

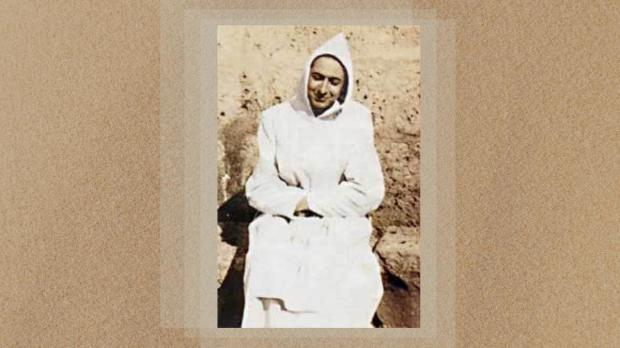

As a teenager, in the city of Oviedo in Asturias where his father’s career led the family, he discovered prayer. At 16, he thought of religious life — but so many other possibilities were open to him! A gifted musician and remarkable painter and draftsman, he dreamed of being an architect, and initially that was the path he chose. He was a handsome boy and an athlete. He was elegant and a tireless dancer, with huge dark eyes that melted girls’ hearts. At the same time, Rafael was serious, pious, chaste, and virtuous.

The Trappist monastery of San Isidro

However, in 1929, his life changed. His uncle, the Duke of Maqueda, devoted his fortune to apostolic works, including publishing religious books. He bought the rights to a biography of Gabriel Mossier, a French military officer who, after France lost the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-1871, entered the Trappist monastery of Chambarand. This book, a success of spiritual literature, needed an attractive cover for the Spanish readership. Knowing the talent of his nephew, Maqueda asked Rafael to take care of it and advised him to visit a Trappist monastery to better understand their world. This is how Rafael arrived at San Isidro … a place he then didn’t want to leave.

Still, neither his father nor the superiors allowed this 19-year-old boy to make such a commitment; they told him to finish his studies. Rafael agreed. However, one evening three years later when he was in Madrid, one of his female acquaintances — who found him decidedly too shy and reserved — decided to talk him out of his religious aspirations. Taking matters in her own hands, she slipped into his bed without his knowledge. Rafael escaped the temptress thanks to a desperate invocation to Our Lady. At that point, he decided to abandon his studies and join the Trappists, which he did on January 15, 1934, taking the name of Brother Maria Rafael. Pointing to Christ, he told his mother, “I am giving him everything!”

It would seem that this edifying story would practically end at this moment, as the novice embarked on his quest for God far from the world, in the heart of the cloistered silence. But it was not destined to be so simple …

At the worst time of the year

Rafael’s first months in the cloister were quite satisfactory, even if he considered himself “a very dissipated novice.” Indeed, he had to restrain his natural exuberance and his joie de vivre in order to obey the rule. Rafael fought victoriously against what St. Paul called the “old Adam” in his ardent desire to sanctify himself, or rather to let himself be sanctified by Christ. Wanting to avoid any temptation to pride, he used to say, “I want to become a saint and not even realize it!” He triumphed over all the natural repugnance that a young man of high society could encounter in monastic privations, especially in the area of food. Unfortunately, this enthusiasm for austerity would cause problems of its own.

He had entered the monastery at the worst time of the year: Lent. The Trappist rigors of that penitential season are extreme, and Rafael didn’t allow himself any departure from the regime. Consequently, he fell ill after Easter. In eight days, he lost 52 pounds, could no longer stand up, and could no longer see. He had previously undiagnosed diabetes, and the doctor warned of the imminent onset of a diabetic coma.

The medical world was just beginning to understand diabetes well and to use insulin to treat it. However, doctors did not yet know how to control it and its evolution, and at the stage Rafael was in, it was practically always fatal. There was no more question of keeping Rafael in the monastery. The abbot gave him a simple command: “Go outside.” It was tantamount to chasing him away. In May 1934, he returned home, dying.

The merits of holy abandonment

The Arnáiz family had the means to provide their son with the best care. A few weeks of treatment put him back on his feet, giving hope for a total recovery, provided he accepted an adjustment to the monastic regime.

Was the illness a sort of warning, which allowed him to measure the price of his vocation? His personal notes reveal a spirituality which would rise to the heights of holiness as the difficulties accumulated. They show that the trial was very difficult and it “thwarted his projects,” but he was already able to differentiate God’s will from his own. If the divine will was to put him through trials, he accepted it, discovering the merits of “holy abandonment.” At the start of the summer, his health seemed to be good enough to consider a return to San Isidro in the fall.

The revolution that broke out in October in Asturias, a prelude to the Spanish Civil War, decided otherwise. The “Reds” went after the rich, the powerful, and Catholics. The Arnáiz were all of these; yet they passed through the violence as if a protective hand were stretched out over them.

Rafael paid for this divine protection: his health relapsed. It no longer seemed possible for him to return to the monastery. The doctor’s prognosis was unequivocal: he would never recover, and would remain a perpetual invalid. He could never be a real monk, and still less a priest.

When the superiors of the monastery received the news, they suggested that he accept the lay status of oblate. He considered this humiliating and well short of his aspirations. Under these conditions, might it not be better to consider that God didn’t want him among the Cistercians, and perhaps not even in religious life?

This vocation of which he was so sure became his cross, leading him to the onset of depression. At that point, however, a disease struck his younger sister Mercedes, and almost killed her, tearing him away from this personal crisis. According to his family, his prayers were what obtained the teenager’s miraculous recovery. Rafael was too humble to think so. However, at the bedside of his younger sister, who was twisted in pain, he had a revelation of what God expected of him. He wrote, “Give me the sufferings that surround me. […] If the cross is necessary for me to love you, send it to me, because the more I bear it, the more I love you!” And returning to write about the difficulties that had overwhelmed him, he added, “I was being selfish.”

Reduced to the lowest jobs

Stripped of what remained of his self-love, Rafael accepted this oblate status, which he found humbling but which allowed him to join his community and integrate into the Cistercian family. In January 1935, he returned to San Isidro. There, his trials resumed. His confessor tried to convince him that his place was not in a Trappist monastery. Then the Spanish Civil War emptied the monastery of its young men, drafted to serve in the Francoist troops. Rafael was deemed to be in too poor health for enlistment, which felt like another humiliation to him. He couldn’t stay at San Isidro, which was too close to the front line; the community had to leave. For the second time, he returned home.

The divine call was still there, however. In 1936, the monks were able to return and Rafael joined them. He was reduced to carrying out the most humble jobs. His superiors confined him to the infirmary, and forbade him to participate in most offices, which were considered too tiring for him. He had to follow a milder regime, which earned him bullying by a brother scandalized by “this preferential treatment.” So, he deprived himself of the extra food he truly needed, until he relapsed and he had to leave the monastery for the third time.

He spent this period outside the monastery painting, producing magnificent, inspired works, such as the image of St. Bernard that would one day be exhibited in his cell.

Rafael didn’t want this seemingly happy existence that provided him with the care he needed. Admittedly, life in San Isidro had become an ordeal for him, but it was precisely there that Christ awaited him. He cried out, “I cannot run away from this cross. I’m coming, Lord!” Despite all the rebuffs, the “rich young man decided to follow.” It didn’t matter what status he would have. He accepted it: “Neither religious nor secular, I am nothing.” “I only want to love.” In December 1937, Brother Rafael returned to the cloister, without illusions: “I am coming back to die here.”

Complete self-offering

He was no longer the same, and everyone noticed it. Strength and light emanated from this exhausted, sick young man, who had been humiliated in a thousand ways. Contrary to custom and to his status as an oblate, the superiors allowed him to take the choir habit, that of “real” monks, letting him understand that being an oblate would only be temporary.

However, Rafael was no longer there. Now engaged in a silent colloquium with the crucified Christ, he would live Lent in intimate union with the Master. He writes in his notebook, “Who, contemplating Your cross, will dare to say that he suffers?” “I asked for a little bit (of his suffering).” From then on, he offered everything. He offered himself entirely, “in order to receive.” As if he felt that it was no longer the time to spare himself, he refused the exceptions he had been granted, declaring with a smile, “I know what I’m doing.” He was careful not to admit that his diabetes was torturing him, that he was excruciatingly hungry and thirsty. On the cross, didn’t Jesus say, “I thirst?” To appease the divine tortures, Rafael deprived himself of drinking. Those close to him would later speak of an “ardent flame of love that consumed him.”

On Holy Thursday, 1938, the abbot authorized him to put on the cowl, giving him the full appearance of the monk he so wanted to be. A week later, on April 26, he breathed his last in the infirmary, wearing the monastic habit. He was canonized on October 11, 2009.