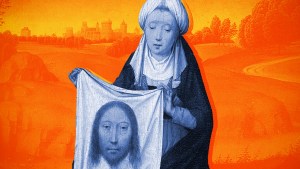

According to tradition, Veronica was a woman (apparently from Jerusalem) who, seeing Jesus carrying the cross along the Via Dolorosa, was moved with compassion and handed him her veil so that he could wipe the blood and sweat from his forehead. When Jesus returned the veil, the image of his face was miraculously imprinted on it. The relic became then widely known as the “Veil of Veronica,” in what seems to be a kind of pun. The sources from which the story is drawn are all in Greek (the name being Berenikē or Beronike, meaning “she who brings victory”), the Latinized Veronica allegedly translates “the true image,” the vero icono of Christ. Ironically enough, several existing images claim to be the original, true relic. One of them, the Manoppello Image.

The story of the Manoppello Imagefollows the legend of the Veronica quite closely. It is said to be the veil Veronica used to wipe Jesus’ face as he carried the cross to his crucifixion. According to legend, the image of Jesus’ face was miraculously transferred to the cloth, which has been preserved as a special holy relic, listed as an acheiropoieta – that is, an image miraculously created by supernatural means or by divine intervention, without the use of human hands.

Now, the Manoppello Image (housed in the Church of the Holy Face in Manoppello) specifically refers to a particular version of the Veil of Veronica – one that does not even mention Veronica, but that claims that the veil had been handed over for generations, until someone finally gave it to a friar.

All the sources for Veronica’s story come from extra-biblical Christian tradition, which has commonly assigned this name to the unnamed woman who hemorrhaged blood for 12 years until she touched the edge of Christ’s garment and was miraculously healed.

While the legend of Veronica’s veil is not based on Scripture, the story of a passerby offering kindness to Jesus on his way to Calvary may well be based in some fact, passed on through oral tradition, collected in the apocryphal Gospel of Nicodemus, mentioned in the famous Historia Ecclesiastica (written somewhere between the years 312 and 324 by Eusebius of Caesarea) and then developed throughout the centuries in other apocryphal texts.

Eusebius tells us that, at Caesarea Philippi, there lived the woman whom Christ healed of a hemorrhage. The apocryphal Acts of Pilate (dated from the 4th or 5th century) identify this woman with the name Veronica. Later tradition (elaborated in the 11th century, according to most historians) claimed Jesus gave the healed woman featured in the gospels a miraculous cloth, which she used to heal emperor Tiberius. This cloth was then understood as being the actual Veil. Some other traditions claim she was married to Zacchaeus, the tax collector featured in the gospel of Luke (Cf. Lk 19:1–10). Finally, the linking of this cloth with that of the Passion occurs relatively late, around the year 1380, in the popular Meditations on the life of Christ.

However, local traditions preserved by Franciscan frairs claim that an anonymous pilgrim arrived at the church in 1508 with the cloth inside a wrapped package and gave it to a doctor named Giacomo Leonelli. He went into the church where he opened it and discovered the image. The doctor went back out only to find that the mysterious pilgrim had disappeared. The image was owned by various families in Manoppello until it was given to the Capuchins in the early 17th century. Since then, it has remained inside the church, safeguarded by the friars.

Some studies claim that the Manoppello Image matches the description of Jesus’ face as given in the Shroud of Turin. Some researchers have suggested that the two images may be connected in some way, although this is more a matter of conjecture than a proven fact.

Despite the many unanswered questions surrounding the Manoppello Image, it remains an object of fascination and devotion for many Christians and non-Christians around the world. Pilgrims travel to Manoppello to see the image, which is only displayed for a few hours each day.