Lenten Campaign 2025

This content is free of charge, as are all our articles.

Support us with a donation that is tax-deductible and enable us to continue to reach millions of readers.

The author of this essay series served as an editor on the Wonder series. Read also about episodes one, two, three, and four.

The fifth and final episode of Word on Fire’s Wonder series on the harmony of faith and science is a meditative and more minimalistic denouement, one that turns from the roiled questions of creation and evolution to the patterned beauty of a medieval window.

The episode opens and closes with the Incarnation—a cosmic event of extremes coming together: angels and outcasts, kingship and poverty, and above all, the all-powerful God and a helpless baby. But an “oft-forgotten paradox” in the Christmas story is “the moral chaos of human history” being drawn into “the perfect symmetry of salvation.” God descends into all our dysfunction to envelop it and redeem it with his love. “Outrushing the fall of man,” the narrator Jonathan Roumie says, quoting Chesterton, “is the height of the fall of God.”

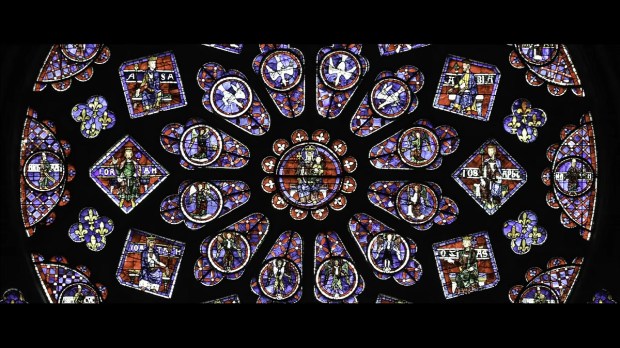

All of this is familiar enough to believing Christians. But in the North Rose Window of Chartres, a gothic cathedral in France, we find an eloquent expression of this foundational idea in the languages of geometry and mathematics. “The biggest challenge of all the process was figuring out a way to film or re-create the North Rose Window at Chartres Cathedral,” the director Manny Marquez explains. Instead of going to France, he came up with a more “experimental world” for the window “based on rear projection screens and custom painting by the sacred artist, Blair Barlow.”

The window features carefully arranged sequences of 12 and a series of ascending numbers called “the Golden Spiral”—“cutting-edge mathematics of the day.” (Beautiful close-ups of a shell, rose, pinecone, and daisy show the same pattern occurring in the natural world.) At the center of this radiant, complex mosaic is Jesus and his Blessed Mother. It is a picture of divine totality and harmony.

Yet incorporated into that same beautiful, ordered picture are ugly, disordered elements: various “bad kings” of Judah—“murderers, cowards, adulterers, and liars”—named in Matthew’s genealogy of Jesus. As we watch Barlow paint recreations of these images, we learn some of the gory details of their lives. Many families have closed their doors on a relative and kept silent about him for far less; yet, in the Chartres window, these disgraceful ancestors are “robed in regal splendor”—proudly displayed as family members of the Savior of the world.

In this collision of opposites, the window poses an invitation to those far from God: “If these thieves, child-killers, and greedy potentates can be God’s family, the very path that God followed into the world, what keeps us from becoming his adopted children?” We have nothing to fear, and everything to gain: “God opens a space for the abuse of our freedom but then powerfully defeats it, integrating it into an astonishingly complex and beautiful design.”

Are faith and science in conflict? The Wonder series will hopefully leave many viewers convinced that the answer is no. It’s a cinematic opening of a door to a whole world of fruitful dialogue down the centuries—one that Marquez was honored to direct for Word on Fire.

“I’ve been blessed to work with them in the past, and it is by far the most rewarding work I get to do,” Marquez says. The filmmaker mentions his secular work, but then—in a line that could just as well have been uttered by one of the many Catholic scientists featured in the series—adds, “There is nothing more satisfying than using my vocation to serve Christ.”