Around this time of year, my mind always turns to T.S. Eliot’s magnificent Christmas poem, “The Journey of the Magi.”

He begins it by alluding to how the holiday finds us huddled inside the comfort of our homes, stockings hung by the fire, hot chocolate in hand, tucked away from the dark and cold. The Magi, however, are on their long journey to the side of Christ, so they’re outside in the winter frost, footsore and exposed to the elements:

A cold coming we had of it,

Just the worst time of the year

For a journey …

As the camels lie in the snow and try to keep warm, the Magi dream of warm summer days. Eventually, after traveling at night and bypassing unfriendly towns, they arrive at the outskirts of Bethlehem, which is, “Wet, below the snow line, smelling of vegetation;/ With a running stream and a water-mill beating the darkness.”

Not exactly the way Christmas cards picture it.

Eliot has a unique way of writing.

His poems are full of jarring images and descriptions that don’t quite fit together, like camels in snow. He often collapses the past and the future into the present moment.

For instance, he does this in “The Journey of the Magi” by describing how the Magi set out from a foreign land, reach their destination, and then return home again. In this way, the circle is closed on the journey and those past events continue to affect the Magi. The journey is ever-present in their minds, the encounter with the Christ-child lingering to the extent that the Magi never quite feel the same again. They’re forever restless, almost as if Christ is pulling them into another life entirely.

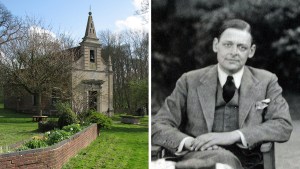

For Eliot, “The Journey of the Magi,” marked something of a turning point in his artistic career. He wrote it in 1927 at the request of his publisher, Geoffrey Faber. The idea was that the poem would be set to a Christmas illustration and then sold as a popular memento. Although the poem has gained much praise over the years, Eliot at one point was nonchalant about it, saying, “I have no illusions about it: I wrote it in three quarters of an hour after church time and before lunch one Sunday morning, with the assistance of half a bottle of Booth’s gin.”

Later in his life, though, he did take the poem more seriously, commenting that writing it helped to get him out of a creative dry-spell and set him on the path to writing his famous poem “Ash Wednesday.“

More to the point, however, is the fact that around the time he wrote the poem, Eliot was beginning to take his Christian faith quite seriously. As an American who very much admired the English, he converted to a tradition within Anglicanism that imitated Catholic worship and many Catholic beliefs. This group, the “Anglo-Catholics,” was often mocked by other Anglicans for their “Romishness.” In many ways, Anglo-Catholicism is for those who love poetry, good wine, and tasteful dress — perfectly appealing for a man like T.S. Eliot, but underneath all the trappings is a serious faith tradition.

Eliot’s faith comes out in the sacramental nature of how he views Christmas.

Just as the sacraments overflow with superabundant grace, so too does Christmas. It’s a holiday that is ever so much more than it seems. It’s a special time during which everything takes on deeper meaning. You hug your kids more closely. The fire in the hearth burns more brightly. Generosity is in the air, an atmosphere of celebration. The season has a sense of enchantment that we look forward to all year. We can hardly wait to begin decking the halls with holly and putting inflatable Santas and reindeer on the front lawn.

At Christmas, there’s a collective feeling that life is a journey worth making. Like the Magi, we pause at the side of Christ in the manger and then circle back round again. Year after year.

In Eliot’s mind, even though the journey is long and difficult, it’s worth making because it unifies our hearts with that of God. Those images Eliot uses that seem so contradictory actually fold into a unity, the unifying love of God for his children. If, at Christmas, camels are yanked from the desert to camp in snow, it’s equally strange that Man and God should become so overlapped. This is the spark of grace. This is the miracle. God has become Man.

The Magi muse, “This: were we led all that way for/ Birth or Death?” In Eliot’s mind, each opposite contains the other. Our rebirth arises from the death of Christ, which was already foreordained even at Christmas. Our death to self for his sake assures this rebirth.

There is so much mystery here, so much grace. Each year, wherever life has taken us during this past orbit of the sun, we circle around to celebrate Christmas once again. The mystery only becomes more profound.