By Katie Kresser, PhD, with Magis Center

The Christmas season is a time especially devoted to children, even in secular society. Across all walks of life, we work to preserve the innocence of the season: the sense of childlike wonder, the joy of surprise, and the celebration of hope. Most of us love images of the baby Jesus in the manger, even if we don’t follow Jesus Himself. We sing “Silent Night” with great tenderness, even if we don’t quite believe the story it tells.

Many of us forget, however, that Christmas is actually the origin of the thing we call “childhood!” That’s because Christianity essentially invented this cherished human phase. Before the news that God was born in infant flesh, “childhood” could not make its mark on the human imagination. We can thank Jesus, therefore, for the modern concept of “the child.”

The Child in the Ancient World

In the ancient world, children were often regarded as burdens to society, expendable, fleeting, and unworthy of too much sacrifice or care. Rates of infant mortality were high, and even the children of nobility were raised by slaves or servants. Children were vessels of potential, yes—but a potential whose realization was uncertain. Perhaps the ancient heart resisted investing too much in something so fragile. Perhaps a hardscrabble world could not look with too much indulgence on “idle mouths to feed.”

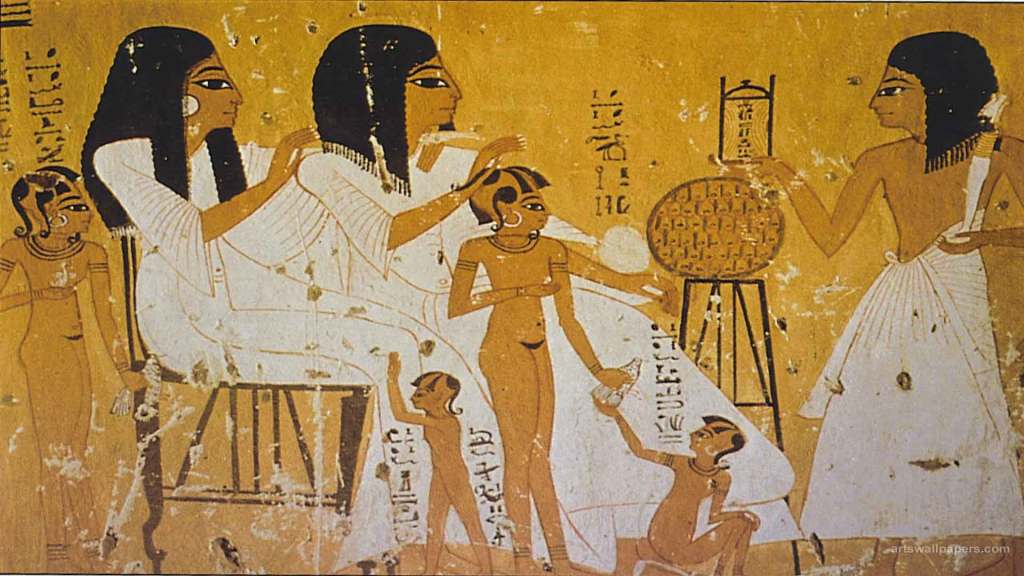

In ancient art, then, we seldom see children that look like children. They are diminutive adults, pasted over with symbols of their future usefulness, pointing to a time when they’ll “pull their weight.” Girl children in ancient Egypt were shown with bodies fully-developed and often eroticized. Boys had adult proportions and wore cumbersome insignia or uniforms. Even in Augustan Rome, whose government policies rewarded childbearing, the royal princes were depicted in heavy togas, gazing with eyes haunted by weighty responsibility.

With Christianity, however, came a new appreciation for childhood. The One, transcendent God had become a baby! Divinity had inhabited the infant form, revealing its grace and beauty—a beauty that lay precisely in “uselessness” and vulnerability! Famously, the first image of the Christ Child appears in the catacombs of Priscilla in northern Rome. Here, a gentle, veiled lady holds a chubby toddler on her lap. Thenceforth, Christian artists would show greater and greater insight into the condition of childhood and all its precious stages—each a poignant revelation of a vulnerable and self-giving God.

Images of the Christ Child in Art History

A fresco of a mother and child in the catacombs of Priscilla is thought to be the first image of Mary holding the baby Jesus. Dating from the 3rd century, this remarkable image (though badly faded) captures infant softness and vulnerability with great skill.

Another early depiction of the Child Christ appears in the icon called the Salus Populi Romani (“Health of the Roman People”), located in the church of Santa Maria Maggiore in Rome. Pope Francis famously visits this 6th-century image before and after trips, and had it brought to St. Peter’s early in the coronavirus pandemic. Here, a toddler Jesus with a large head and chubby cheeks looks tranquilly up at His mother.

In the late Middle Ages and early Renaissance, it was common to depict the Child Jesus playfully holding a goldfinch. In addition to hinting at children’s natural affinity for small animals, the goldfinch motif summons a host of other resonances: God’s care for small things (“his eye is on the sparrow”), St. Francis’s sermon to the birds, and in the goldfinch’s colors (blood red and royal gold)—a reference to the Crucifixion.

One of the most beloved images of the child Jesus can be found at the monastery of San Marco in Florence. In this fresco by Fra Angelico, Jesus’s childlike innocence, tenderness, and earnestness is on full display.

The artists of the High Renaissance in Italy, including Michelangelo, Leonardo, and Raphael, specialized in depicting correct human anatomy—including the anatomy of children. In Leonardo’s Madonna of the Rocks, a cross-legged Jesus raises a chubby arm to bless His cousin John the Baptist. Charmingly, an angel keeps Him from toppling over.

By the late Renaissance, it was common for artists to depict a somber Mary with a sleeping baby Jesus, pointing toward the Crucifixion. In Bellini’s tender version, a faint foreshadowing of pain haunts the baby Jesus’ features. Mary’s hands are joined in prayer as she solemnly contemplates this paradox of doomed innocence.

A master of flickering flame, Georges de la Tour painted some of the most captivating Nativity scenes in Art History. In this version from the Louvre, the swaddled baby Jesus looks like a true newborn. Tiny and helpless, he glows with aching, poignant vulnerability.

The child Jesus of Caravaggio’s Madonna di Loreto, in the Roman church of Sant’Agostino, is powerful and wriggly. As he reaches out to bless visiting pilgrims, he seems ready to burst from his mother’s arms.

In 1850, the British artist John Everett Millais painted Christ in the House of His Parents, showing an adolescent Jesus who has been helping Joseph with carpentry. Jesus has cut his hand in a way that foreshadows the stigmata; his cousin John brings water to clean and “baptize” the wound. The scene is sweet, but also full of portent. This boy will one day die for our sins so that we can dwell with God.

Thanks to its reverence for the Child Jesus, Christian culture has helped the world treasure childhood in all its stages, from the moment of birth until the threshold of maturity. That legacy is still with us today – particularly in the modern celebration of Christmas.