Hell on earth is what the passengers of Flight 571 experienced on October 13, 1972.

As the members of the Uruguayan “Old Christians Rugby Club” and their families were on the way to Chile aboard a Fairchild FH-227 D aircraft, the unthinkable happened. The plane hit a mountain peak, and crashed onto a glacier at an altitude of almost 12,000 feet.

In the end, only 16 of the 45 passengers survived, after fighting death for two months at the cost of unimaginable decisions and sacrifices. The story is familiar to people around the world, thanks in part to the 1993 filmAlive.

Discovering God’s goodness

This year, on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the crash, one of the survivors spoke with Aleteia about his experience.

Despite feeling anger and despair, Zerbino felt God’s unwavering support in this desperate situation. His understanding of faith was transformed. “The idea I had of God when I was a child was (a God) who was a punisher,” he tells Aleteia. “In the mountains, we got to know a good God. Despite everything that was happening he was with you, he accepted you, he accompanied you. Our God was love.”

Two of the survivors, including Zerbino, risked their lives by descending the mountain in the extreme cold to seek help, since the search had been called off after 10 days of unsuccessful efforts. Before descending, Gustavo put all his energy into helping try to save the seriously injured, by bandaging and treating their wounds with the means at hand.

“In rugby, the hefty, the tall, the small, the slow, the fast: everyone has to play a role. I had studied three months of medicine (…) and I had to carry out medical tasks with Roberto, who had studied six months of anatomy,” he explains. “Each of us had a role … I was the one who had to be a doctor, who had to climb the mountain (to get help). I had many roles, just like everyone else.”

Doing the unthinkable to survive

After several weeks, some felt they had no choice but to resort to eating the flesh of those who had already died in order to survive, having even tried to eat leather belts first. Some, unable to face such a transgression, let themselves starve to death. Others explicitly gave the other survivors permission to consume them if they died, including Gustavo Nicolich, who was just 19 years old.

“We made a pact of love, of giving our body, as Nicolich wrote. He made a gift of his body and the next day he was dead. It’s a very powerful feeling. We had to overcome a psychological, physiological, religious and cultural taboo,” Zerbino explains.

They were all Catholic and would later explain that it was their faith that allowed them not only to survive, but also to overcome the psychological consequences of such a tragedy.

Their choice obviously caused a great deal of controversy, criticism, and judgment –especially since the survivors justified it at the time by referring to Christ’s sacrifice on the cross for the salvation of mankind, and the institution of the Eucharist on the eve of his Passion.

At the same time, the resilience of these young men – all of them in their 20s with the exception of one 36-year-old man – is unquestionable. In the end, the Catholic Church decided in their favor: Pope Paul VI absolved them of any guilt.

50 years later, a Mass on the spot

Fifty years after this tragic event, an Argentine priest, Fr. Diego Maria, was contacted by Zerbino. He asked the priest to go with him on his return trip to the site of the tragedy. Accompanying the survivor and his family, Fr. Diego Maria climbed the mountain as if it were a pilgrimage.

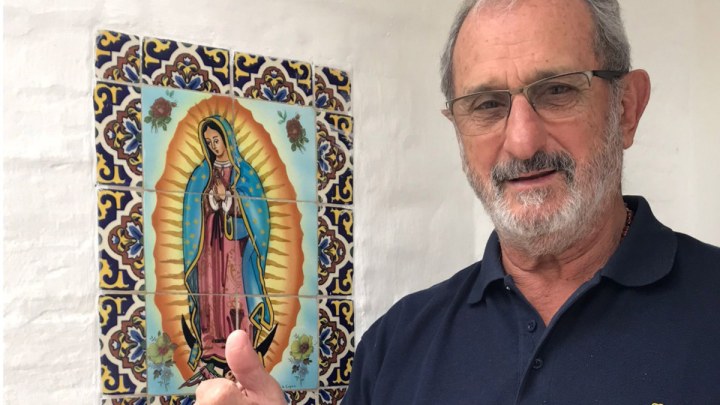

Once he reached the summit, he celebrated a Mass in memory of the dead. “I prayed for each of the people who died there, on that mountain range,” the priest explains. Part of the plane was used as an altar. Zerbino also carried grass from the Uruguayan rugby field where he played with his friends. He is a very devout man, with a special devotion to Our Lady of Guadalupe, whose name his youngest daughter bears.

Pope Francis himself reacted to this year’s commemoration in a letter dated October 10, in which he called for prayers for the families of the dead, with special emphasis on the mothers of those who died in the accident. He spoke of their “heartbreaking maternal pain which, lived in the light of Easter, was able to transcend itself and become a sign of a life of service for love.”

The pope also expressed his gratitude for the witness given by the rugby players, who never stopped praying and trusting in God. “They held on to the most precious thing they could have, along with the desire and will to look forward and keep on living,” the Pope wrote.

Finding God in suffering

How can we find God in this suffering?

We must “find the risen and pilgrim Christ in history, who knows the suffering not only of those who climbed down the mountain and the joy of those who arrived, but also the sorrow of these families who, 50 years ago, wept for the loss of their children. But those tears, placed in God’s hands, have the hope of a joyful resurrection where we will all be able to meet each other again,” explains Father Diego Maria.

Zerbino told Aleteia, “We returned from the Cordillera in a very great state of grace. Despite what was happening, we gave thanks every day. And we lived in a state of acceptance. When you refuse to accept reality, you suffer. There we learned that no matter how much we cried, no matter how much we screamed, we would still be cold, still be hungry.” Acceptance helped them to face the situation and act, trusting in God.

One of the survivors of the crash, Nando Parrado, published a book in 2006 called The Miracle in the Andes. The miracle isn’t so much the survival of these 16 men, but the persistence of their faith after experiencing inconceivable suffering. Theirs was a faith that could move mountains.